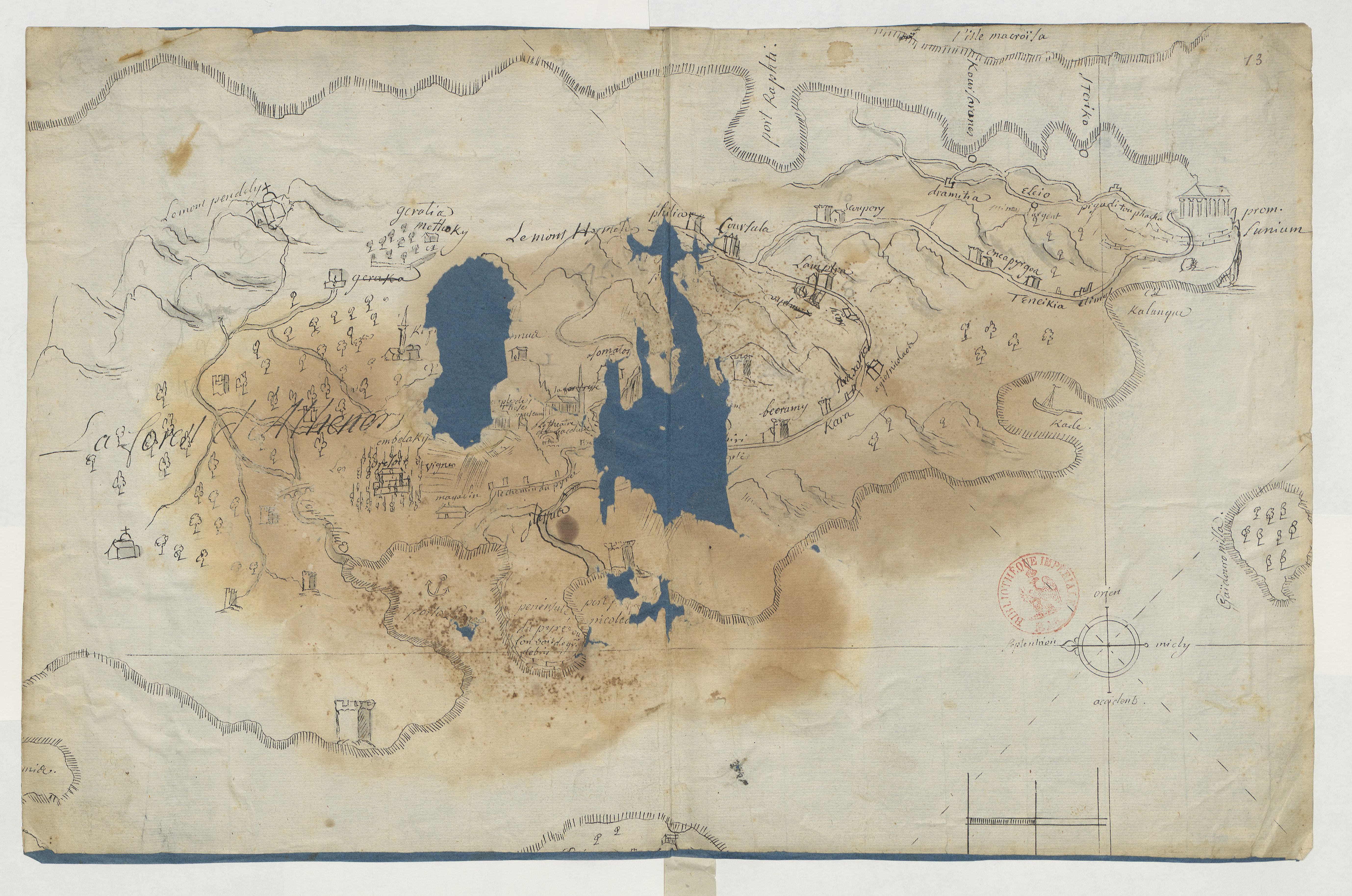

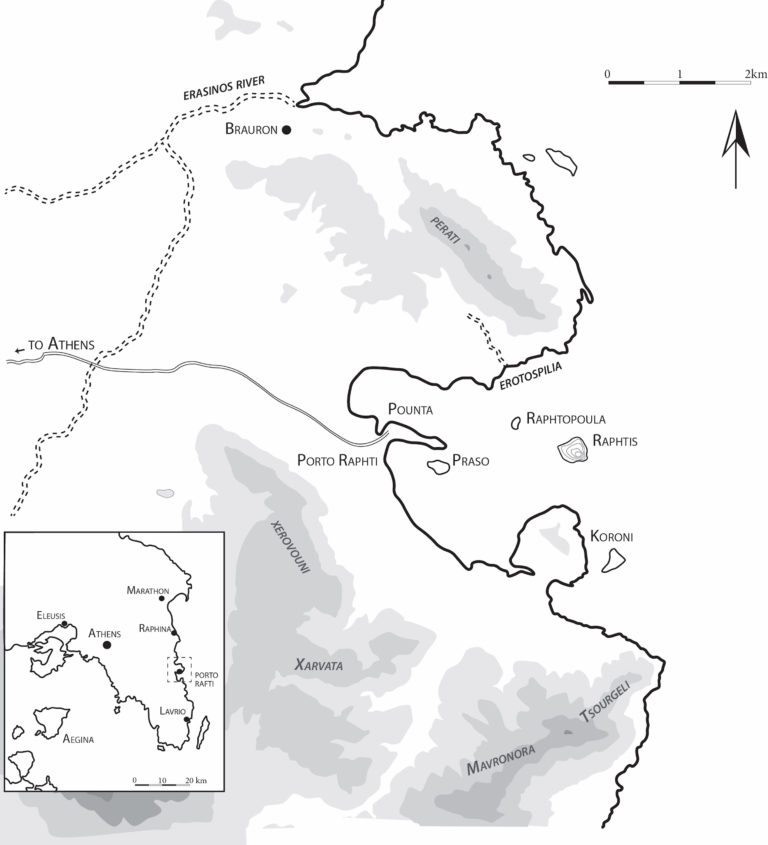

The modern town of Porto Rafti sits astride a bay that provides an excellent natural anchorage. The bay measures 2.1 kilometers wide at the mouth and 3.1 kilometers long from east to west. It contains three islands – Raftopoula, Raftis, and Praso – and two peninsulas – Pounta and Koroni – the latter of which is flanked by another island, also called Koroni.

The official name of the town is Limin Markopoulou (the harbor of Markopoulo, a city inland to the west), but everyone calls the place Porto Rafti. The name derives from a heavily damaged Pentelic marble statue originally made in Roman times that was installed atop the island of Raftis in the bay at some point in the early modern past. Local lore has it that the statue represented a tailor (Raphtis in Greek) and once held a pair of golden scissors. However, scholars agree that the statue, which still sits on the peak of Raftis, probably represented a seated goddess instead.

A variety of archaeological evidence in and around the bay has been produced by research in the last 150 years. In the 1950s, the Greek archaeologist Dimitrios Theocharis noted that the Pounta peninsula must contain the oldest settlement in the area, based on his observation of ceramics and obsidian on the surface. Theocharis also observed that an EBA sherd scatter on the small islet of Raftopoula contained fragments of marble Cycladic vessels, which he concluded should have come from a cemetery on the islet. Visitors from foreign schools have likewise noted the presence of Final Neolithic (FN) and EBA pottery on the peninsula and islet.

The most spectacular assemblage of Late Bronze Age (LBA) evidence from the area comes from the Late Helladic (LH) IIIC cemetery at Perati. Between the late nineteenth century and 1960s, over two hundred chamber tombs were excavated on the south slope of the Perati massif that dominates the north half of the bay of Porto Rafti. Final Mycenaean mortuary practice is also evident at a number of other locations within the immediate surroundings of the bay of Porto Rafti, including Ligori and Drivlia. Despite this mortuary evidence, settlements and structures dated to the period have not been identified to date.

While there are no documented remains from Porto Rafti between the end of LH IIIC and the Archaic period, historical sources attest to the presence of two demes on the shores of the bay, one in the north (Steiria) and one in the south (Prasiai). Both areas have produced sporadic archaeological remains. Regarding the Hellenistic period, ruins on the site of Koroni were first documented by Lolling in the late 19th century, then mapped by McCredie, Steinberg, and Jones in 1959. McCredie and Steinburg returned to the site to conduct excavations directed by Vanderpool in 1960. Considerable debate currently surrounds the history of the fortifications and topography of Koroni. The excavators concluded that the site was founded specifically to serve as a base during the period from 266–262 BCE and had no relation to the historical deme of Prasiai, a conclusion that has been debated back and forth by Hellenistic scholars ever since. Some have rejected this limited-use history of the site on logical grounds, and argued that the quantity and nature of the material and architecture do not fit the notion of a short-term occupation by a military force, and suggest instead that the deme of Prasiai extended onto the site of Koroni from its core position on the mainland across the isthmus. Notwithstanding the logical strength of these arguments, finds from earlier periods had not been documented on the peninsula prior to the BEARS project.

In terms of surface scatters, Roman and Byzantine pottery has been reported from several of the islets in the bay, including Raftis, Raftopoula, and Praso. The presence of the Roman-era statue of Pentelic marble (the “Raftis” that gives the bay its name) installed at the peak of the Raphtis island also speaks to activity in the region in later antiquity, although its identity and history of installation or use have been debated. The bay’s role as a prominent regional harbor during late antiquity and the middle ages is also attested by travelers’ accounts.