Joseph (aka, Joey) Frankl is currently a PhD candidate entering his fourth year in the Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA) at the University of Michigan. He came to work on the BEARS project last summer fresh off a long stretch of regional survey with (and highly recommended by the directors of) the Western Argolid Regional Project (WARP). Joey brought a thoughtful and diligent approach to survey in Porto Rafti during the 2019 season, and will be taking on an important role analyzing the project’s Roman pottery in subsequent seasons. For now, he is spending the summer basking in the glow of a significant recent triumph – the successful completion of his doctoral program’s preliminary exams. BEARS project management caught up with him at his home in Ann Arbor on a recent, sunny June afternoon and he was gracious enough to interrupt his day and give us the following interview.

SCM: Let’s begin with the basics: you are currently working on your PhD in Classical archaeology at Michigan. What inspired you to pursue a graduate degree in this area, and why did you end up choosing this particular program?

JVF: Well, I wish I had a better origin story in some ways! In fact, I think it’s more of an anti-origin story, because I can’t really identify any clear beginnings. I took a Classics course my first year at Macalester College, where I did my undergrad, and the professor who was teaching it, Andy Overman, was directing a project at Omrit in Israel. He gave me an opportunity to go and work with them, which was really generous, but the project was actually kind of not optimal. It wasn’t a great year to be there, because it was the last year of that particular campaign; everyone got food poisoning; there were these horrible gnats. I mean, I liked the project, but I wouldn’t say that I fell in love with archaeology right away.

But I kept taking archaeology courses the rest of the way through college, and I realized that what I liked about it was that it was essentially history, but without the texts. I suppose I’d grown up with the idea that history is something that’s told through literature and texts. The idea that you could tell the story of the past through stuff instead – everything from mundane objects to huge, monumental buildings – was really revolutionary to me. In the end, that was what really attracted me to archaeology. And the more coursework that I took and the more scholarship that I actually read, the more interesting I realized the questions you could answer from material worlds were. There were all these great theoretical debates, and big historical questions about the long-term of human existence that could only be addressed by looking at objects – and I just became increasingly enchanted with the discipline. So I’d say the more I do archaeology the more I love it, which is a good feeling.

Then, I fell in love with Greece and fieldwork, too.

SCM: Yeah, that happens to a lot of us – it’s like falling into a swamp that you can’t escape, but in a good way. So, why Michigan?

JVF: Right – well, I was deciding between a couple of different programs, but what attracted me most to Michigan was that there was a big group of graduate students and a lot of archaeology students specifically. There aren’t a lot of programs that have that kind of sizable community. I knew from the start that I didn’t want my graduate career to solely be preparation for an academic job that I probably won’t get after six or seven years, so I wanted it to be an awesome experience when I was there. The vibe I got at Michigan was that the students not only had fun but that there was a lot of substance to their experience in terms of the intellectual environment, and they had a real feeling of camaraderie. And that’s been actually true.

The funny thing is that when you make choices about graduate school you’re working with such partial information. But I basically decided that having a great group of peers was my top priority, and Michigan really stood out in that area.

SCM: That makes a lot of sense – and it sounds like you made a great choice. I like your point about how you really have very little idea what you’re doing when you are choosing a grad school. I definitely went to Stanford for my PhD for reasons that ended up seeming really ridiculous when I reflected back on my actual experience in that department.

JVF: Exactly – the things that actually end up being important to you, like writing your dissertation or the classes you take, are basically impossible to predict when you’re applying. It’s just a weird constellation of chance and individuals.

SCM: Very true! But if you don’t have solid friends in grad school you will probably be miserable no matter what, so I think you were smart to look at camaraderie as an important sprocket in the decision-making process.

JVF: Yeah, I remember when I was making that decision in 2017, I already knew that the chances of getting a good job were pretty daunting. So I didn’t want to do the whole graduate school thing just for the sake of getting a job – it had to be pleasurable in some way.

SCM: Well, fortunately, these days the prospects for jobs are looking way better! Ahem. Anyway, going back to the doctoral program, where are you currently in terms of progress and what kinds of research are you pursuing?

JVF: I just finished my third year, which means I’ve now advanced to candidacy. I did three years of coursework and many, many exams. I believe there were six different types – French, German, Greek, a qualifying exam, prelims, and a history exam. I spent a lot of my time worried about those things and trying to finish term papers. It was very rigorous, and I’m definitely a little bit tired at the end of all that. But now I actually get to focus on my own research and some of the field projects that I’ve been involved with. My dissertation is going to be on the Roman Imperial economy, basically the 1st century BC to the 3rd century CE, in Greece. There is not a lot of synthetic work on that topic, and I’m really interested in this idea of economic integration and the way that imperialism impacts peoples’ relationships with resources and material objects.

I’m still trying to figure out what that’s specifically going to look like in terms of a dissertation. That’s actually something I wanted to talk to you about at some point: framing a dissertation and how one takes these big questions and connects them to a focused archaeological project. It seems like your book project was really successful in this regard.

SCM: Hmmm, well, for me it took a long time to get to the point of a clearly useful and coherent project! I know everyone has a different process for this kind of thing. But for me, I always have to let my research projects develop through the writing process itself. I mean, you have to come up with some kind of plausible-seeming framing from the beginning, but I ended up writing something totally different for my dissertation than what I planned from the start. And that’s been true of my second book as well. I only ever seem to find what’s interesting in a topic when I start writing about it, and then there’s this great eureka moment when you really traction onto what’s interesting and valuable there and what your contribution will be. I think for most people it’s a whole process. We can talk about that more later.

JVF: Yeah – so, in any case, I’m basically right on the precipice of starting the dissertation. I’ve got some other things going on, too. I’m involved in the Western Argolid project like some other folks on BEARS. And I’ve got several other ideas for articles I’d like to write up at some point, things that have emerged from term papers and other creative interventions I hope I’ll get a chance to work on. I just felt like I had no time the first few years.

SCM: It’s a really important inflection point in most people’s academic careers – you’ve been in classes basically for your whole existence as a sentient human being, and now you’ve reached this cliff edge where you careen off into the abyss of independent research. Most people are definitely glad to say goodbye to courses at this point. Looking back, though, could you pinpoint a favorite course, or a most valuable experience in the early stages of your grad career?

JVF: Absolutely. There was a course I took my second year, Mobility, Connectivity, and Global Networks in the Western Mediterranean, which is not my geographical area of interest, but it was an amazing seminar. Every single person in the room had smart things to say every week, nobody ever wanted the class meetings to end, and everyone always felt really energized afterwards. It was taught by Linda Gosner who was a postdoc at Michigan and did her PhD at Brown on Roman Iberia. So, we shared an interest in the Roman Imperial economy, although she’s focused more on the western Mediterranean. She brought a lot of enthusiasm to the material and also structured the discussion in such a way that we were able to work together through these difficult theoretical texts but also look closely at the archaeological applications of those theories. We even created a reading group out of that seminar. It’s those types of peer interactions, where you’re really helping each other build knowledge together – that’s what I am going to miss the most about coursework.

SCM: That sounds like an amazing seminar! Would that all grad seminars could be so good.

JVF: Right – someone once told me that you should count on about 50% of grad seminars being just generally bad.

SCM: Ha – I have never heard that stat before, but it sounds pretty accurate to me. One way that you’ll probably continue to have this kind of peer fellowship, even as you do independent research, is of course through fieldwork. So, turning to fieldwork, I know that before coming to BEARS you worked on another survey project, in the western Argolid. What other kinds of projects have you done thus far?

JVF: My first excavation was at Omrit in Israel, as I mentioned earlier. I also excavated at the Agora in Athens for a summer, and did a kind of rescue excavation in Corinth for a few weeks in 2016. So, I’ve had some excavation experience, and then WARP and BEARS, and I also worked in Turkey at Notion, which is my advisor Chris Ratté’s project.

SCM: Wow, lots of different places! Would you say that you prefer excavation or survey projects, and why one or the other?

JVF: A much debated question! I think I prefer survey. But they’re both enjoyable for different reasons. Digging in dirt is a sensational experience, and there’s this joy in discovery. I love survey, but rarely do you find amazing, well-preserved objects. In Israel, I helped excavate a fresco-decorated wall, and that was a pretty painstaking but also extraordinary experience.

But survey is so amazing because you are embedded in the landscape, which creates this relationship with the present. Survey combines the contemporary and the old in this unique way that you don’t necessarily feel when you are digging. When you are digging you’re really just engaging with the archaeological record and you don’t really think that much about the modern environment in which that record is embedded. But I like the idea of the past in the present, and I think that’s one thing that survey does really well. Survey is also a much more embodied experience of moving through the landscape, which captures both time and space, and you just don’t get the same feeling in excavation.

SCM: That’s an interesting observation, that survey work provides us with a really unusual way of experiencing time and space. And maybe a glimpse into how any human, ancient or modern, would have moved through the same landscape. Although I hope for the sake of ancient people that there were fewer maquis bushes around back then.

JVF: What is the history of maquis? Is it a diachronic phenomenon? Do we have any texts where Aristotle complains about maquis or something?

SCM: An important question! I’m not sure exactly, but one thing that’s amazing is to look back at photos of the Greek landscape from the earlier 20th century. The Mazi Plain, where I worked before BEARS, is almost totally free of maquis in some of those photos! And Koroni is the same. The issue seems to be that grazing regimes were much more thoroughgoing and intensive back then. Sheep and goats will eat the hell out of some maquis: it’s one of their favorites. So I think it’s safe to say that in any period when there were a lot of herd animals, there would have been less scrubby vegetation around in the Greek landscape. But it is hard to say exactly.

JVF: Perhaps this would be a good dissertation topic for someone.

SCM: Indeed! Now, maquis is one of the many glorious aspects of fieldwork in Greece. You said earlier that you fell in love with doing fieldwork in Greece specifically. Aside from getting stuck in thorny bushes, what do you like particularly about research and fieldwork in Greece?

JVF: I did think about doing my dissertation about Turkey, but I ultimately settled on Greece. In some ways the feeling of being in Greece is almost indescribable – the smells and sounds, the way that the mountains and ocean are so close to one another. But I think the coolest thing to me about being in Greece is the way that you experience these little worlds in themselves: sometimes you can take a pass through a little valley, and end up in a totally different environment – I guess what Horden and Purcell call microregions. I really find that feeling of escaping and being immersed in these landscapes and whole other worlds really intoxicating. Not to mention a pleasant contrast to being in an academic context the rest of the year.

It is interesting because in Porto Rafti we have that similar experience even though we’re in an urban context. So when we take the boat across to Raftis island it’s a totally different world, and same thing with Koroni. You get the same feeling of escaping into a small, independent world within an incredibly beautiful landscape.

I’ve also had the chance to make a lot of great friends who live in Greece and are Greek, and I think the more you develop these kinds of social ties the more you are going to be drawn back to the same place.

SCM: That’s a great point – I noticed how closely you bonded with our Ephoreia supervisor Herakles last summer! Another new social tie to keep you yo-yo-ing back to Greece

JVF: Yeah, I need to send him an email!

SCM: I’m sure he’d absolutely love to hear from you. I’m now also realizing that a lot of the reason that I love going to Greece is that it is where I spend time with most of my best friends. This has been a weirdly lonely summer in that regard. But, returning to fieldwork, one thing that is interesting to me is that you’ve decided to work in Greece but on Roman material, and in particular that you are looking at Roman pottery in some of your fieldwork projects, including BEARS. Now, it’s probably not too controversial to say that Roman pottery is not the most obvious thing to get excited about if you’re a Greek archaeologist. Not to say that it’s not interesting, but, for example, I don’t think I ever even saw a picture of Roman pottery in most of my Greek archaeology classes in school. So, you’ve taken a relatively unusual tack in this regard. Where has your interest in Roman Greece and Roman pottery come from and why did you decide to pursue that as a research specialty?

JVF: That’s a great question. Ultimately there are a lot of things about the Roman empire that I find personally very interesting. I’m interested in imperialism in general, and in the way that – in the case of Rome – having a huge empire that is so interconnected changed the way that people viewed their relationship to the material world. Although there are other places and periods of antiquity where you can get a look at imperialism, that kind of hyperconnectivity at scale is particular to the Roman period. There are all these cool developments: mass production and trans-regional, trans-provincial trade, the circulation of objects at a large scale, and I find all of that stuff really compelling to think about.

There are lots of angles from which a person can explore their intellectual interests. In my case, I came to Greece and loved it and made lots of friends there, so then I found a way to examine research questions I found interesting in a way that pertained to that environment. There’s also a lacuna in the scholarship. So, there has been a confluence of various different things that led me to get into the Roman period in Greece specifically. I guess it might not seem as exciting to other people…

SCM: No way! I mean, I am on the record as kind of a Roman disparager, but the way you explain it makes it sound like a super interesting project. And you’re right that there’s a big hole in the scholarship there, and there is a ton of material. It’s great that there are smart people like you who are motivated to wander in there and tackle it.

I guess it’s not really fair to ask this since you haven’t had much of a chance to study the BEARS material yet, but do you have any first impressions of what might be cool or interesting about the Roman pottery from Raftis? Is it going to be awesome or kind of useless for your project?

JVF: I think it’s going to be great! Last year I noticed quite a bit of fineware and quite a lot of amphoras. I’m interested in the amphoras because they are going to tell us about trade and production, as will the fineware to some extent. I think it should be an interesting assemblage. It seems like there might be some early Roman material, which would be exciting, but I’ll have look at it a little more closely. The majority of what we collected is definitely Late Roman, and a lot of it is quite nice – the combware is really beautiful.

SCM: It should be exciting to try to figure out what people were up to out there in the Roman period.

JVF: Right! From what I’ve read about Attica and the Roman economy, it seems that there was a general interest in islands, and that seemed to be happening in general in the Aegean then too. The Aegean becomes hyperconnected, and islands seem to play a role in that. It will be interesting to see what the node of Raftis was doing in this larger network. And that goes back to what’s so exciting to me about the Romans – every site is part of this big picture narrative of globalized, interconnected economies. It’s cool that we will be able to make an argument and contribute to that kind of debate.

SCM: Cool stuff, for sure. Hopefully we can actually go to Porto Rafti again and work on these issues soon. What did you think about Porto Rafti as a place to live and work? I know it is very different from the western Argolid in a lot of ways.

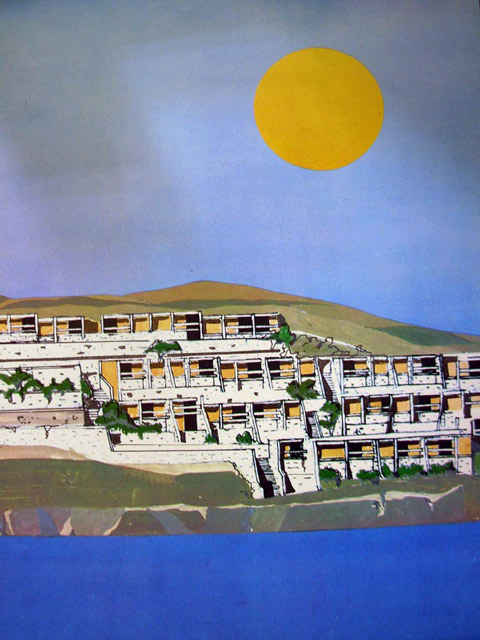

JVF: It was unique for me among my experiences in Greece. It’s definitely a vacation town and really lacks a central civic space, which is a key feature of most towns in Greece. But I did like being there. I went on a lot of long runs around the city and the region. One thing that I loved is that once you got just over the ridge west of the town you are suddenly in this big arid agricultural landscape, but to the east it’s a fabulous view of the sea, and I liked going back and forth between those environments so easily. I’d like to explore it a little bit more – it’s a big town and hard to get around too much without a car. I didn’t really feel I got a good sense of the community or have as much contact with individuals as I would have liked. But my impression is that a lot of people just come in on the weekends, so maybe there’s just not that much of a community to start with. I was actually at a friend’s house – he’s a Greek American – and he had a coffee table book from the 80s about architecture in Greece, and there were a bunch of houses on the slopes around in Porto Rafti in there, which I thought was funny.

SCM: That is awesome – who knew Porto Rafti was renowned throughout the land for its avant-garde 1980s beach houses!? But, yeah, it is a funny town compared to your normal Greek village in a lot of ways – no plateia! Can you imagine? We’ll have to keep trying to figure out what makes it tick and find the community in future BEARS seasons. Okay, last question: I know you’re an avid reader and a fine connoisseur of culture in general. What have you been reading or watching to relax and/or avoid excessive doomscrolling recently?

JVF: Oh yeah, I’ve been reading a lot and watching a lot of movies. I got a subscription to the Criterion channel which has a lot of old art films that I’ve really enjoyed watching. The last one I watched was called Old Joy, a movie from the mid 2000s about two old high school friends who go on a backpacking trip in their 30s. It’s all about melancholy and friendship and paths going different directions – it’s really beautiful. But I’ve watched a lot of excellent movies – it’s a great way to keep your mind off of everything horrible that’s happening out there. Movies are better than tv for that, because you actually have to focus on them. For books, I recently read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, and it is so great – I recommend it to anyone! His descriptions of eating bread with olive oil…

SCM: Whoa, it sounds like you’re torturing yourself – reading about being in the Mediterranean eating freshly baked bread with olive oil during a summer like this!

JVF: Yeah, but it’s totally worth it! Seriously – great book. And I don’t even generally love Hemingway. I’m also rereading Housekeeping by Marilyn Robinson, which is also a really beautiful book that I recommend to everyone. It’s about two orphans being raised by their aunt in Idaho. Anyway, other than that, I have just been trying to enjoy the sensual pleasures of being in Ann Arbor.

SCM: Indeed! May the pleasures of Ann Arbor be manifold and keep you satisfied through the rest of the summer.