We make our way up the stairs to the entrance and I am glad to step into the air conditioning as the heavy, metal doors swing open and the guard greets us. We sign in and deposit our backpacks in our designated cupboards. As we head downstairs, I cannot help but smile in anticipation; if you have never been in the storage room of a museum you have not really felt like Indiana Jones. I was never into the cowboy-hat and whip aesthetic but as I descend the stairs to head to the small courtyard where work, I cannot help but feel like I am missing important apparel. The ambience of the storage room is that of a mission briefing before Indie takes off on an adventure; rows and rows of catalogued objects, nooks filled with reconstructed pottery vessels, their tags sticking out in the dim dusty light with their distinctively flashy colors, the musty scent of washed clay permeating the room, all hint at muted adventure. These visual and olfactory stimuli present us with an aura of worlds silenced as we descend the staircare. I get the distinct impression that museums exist in a state of liminality, their residents waiting for the right scholar to give them their voice back, or anticipating the glance of the patrons so that they may relive their glory days. In order to reach our working area we have to walk across most of the extensive storage space, and so, as I do every time I am scheduled to work at the museum, I try to quickly make out the writing on the tagged boxes rising high above me. The narrow, high-ceilinged corridor leading to a small courtyard is lined with box upon box of catalogued artifacts, the shelves extending high above us. Some boxes contain pottery, some coins, and some bones; I am always struck at what constitutes archaeological evidence as I hastily try to read the labels on the boxes – vessels used for food, the means to buy that food, and, of course, the remains of those creatures who constituted food in the ancient past!

As we step into the shed our team-lead opens the massive iron door separating the antechamber from a miniscule courtyard. We head to the workroom allotted to us by the museum to collect clean bags artifacts that we have already washed and that were set out to dry the night before, as well as to collect the bags of the unwashed finds from yesterday’s haul. Our small space at the back of the museum becomes alive with precise activity as, by now, all team members are familiar with the tasks to be performed. We each fall into a routine as we collect the washed finds, set up the weathered screens upon which we are to lay out the freshly washed pieces of diagnostic pottery, and position ourselves on our make-shift stools. We begin to clean the finds from the previous day’s workload. In the beginning, as we race to beat the sun’s glare, huddled at the far end of the small courtyard in the shade provided by the tall wall surrounding the museum, there is very little conversation. Our aim is to finish up the cleaning before noon, so that the sun does not burn us to a crisp.

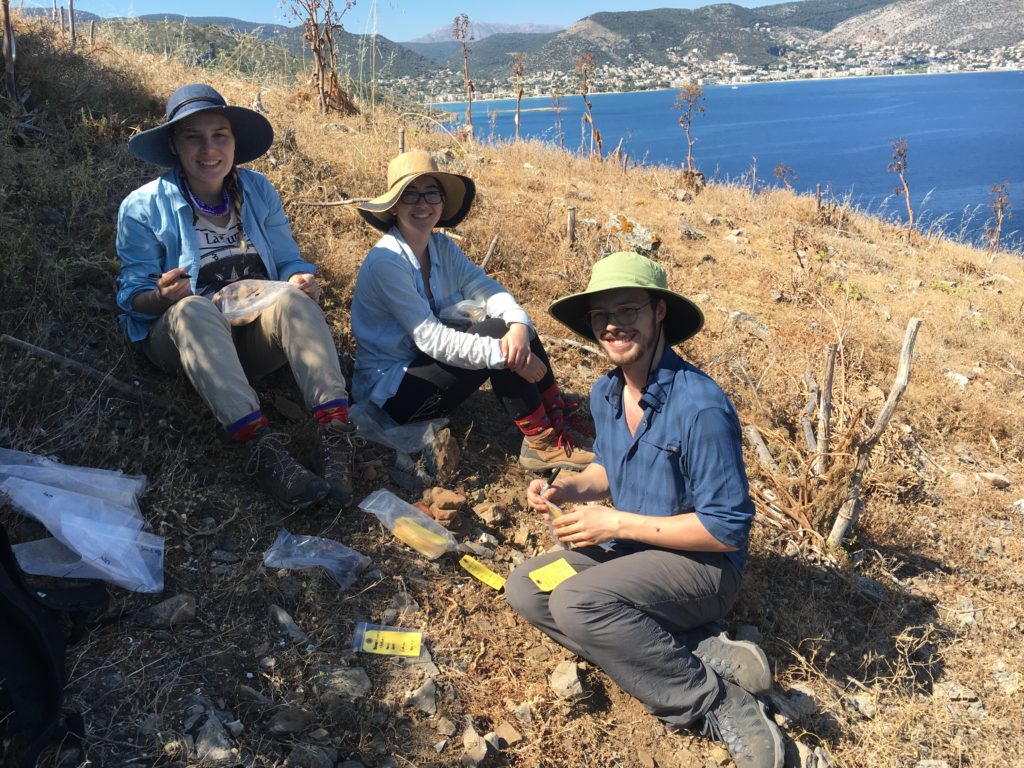

But as the hours pass by in companionable silence, and as we realise that we are making good time, conversation sparks. Unlike the perfunctory, exhausted commentary of lunch breaks in the field, museum conversation usually aims to contribute to our growing camaraderie. Though in the field we each tend to look out for each other by making sure no one gets left behind (*cough* babysitting me *cough*), even distributing the growing weight of our backpacks as the finds accumulate and our stamina decreases, in the burning shade of the concrete wall, we are now interested in learning about each other’s personal lives. Discussion about each student’s aspirations, and what brought them to work at BEARS, are common topics. And even though our acronym animal does not travel in a pack, I cannot help but feel that I have become a part of one; the first ever bear pack to exist.

I struggle to get up to wash the dirt from my bowl, the finds now almost all cleaned. It is always a surprise how physically tiring it can be to crouch for hours. Initially, I had thought that my days working at the museum would be less physically demanding than days in the field. And while there is certainly truth to that, my hip joints still hate me for straining them during those days at the museum. By the time I rinse out my bowl and place the washed items on a screen in optimal order for drying, the rest of my teammates have also finished up. After making sure all the cleaning supplies are put away, and that the netted stacks are in position under the heat of the sun, we head into our small workroom for our lunch break. So late in the day, the heat of summer is stifling. In the museum there are no briny breezes to soothe the heat from our bodies; there is only the musty scent of a museum storage room mixed with the mountain air idly blowing in the room from the two wide open windows. My hips are slightly less strained and relaxing by the minute as I sit in the old-school wooden chairs which normally grace old timey men’s coffee houses from the ’70’s. But as I hungrily bite into my spinach pie, courtesy of the best Greek bakery of all time discovered by our museum team-lead, I unceremoniously snort in disbelief at a comment from one of my teammates; something about him writing the best footnotes, a comment I know to be a lie, since none can match my footnote-writing expertise. And so, when our lunch break is over, and we proceed to the next part of our work for the day which entails organising, counting and cataloguing, I challenge my (naïve) teammate to a footnote composition face-off, incredulously realising that archaeology has wormed its way into my heart.