Editorial Note: This post was written by Irum Chorghay, a University of Toronto student, about work during the final week of the 2019 season.

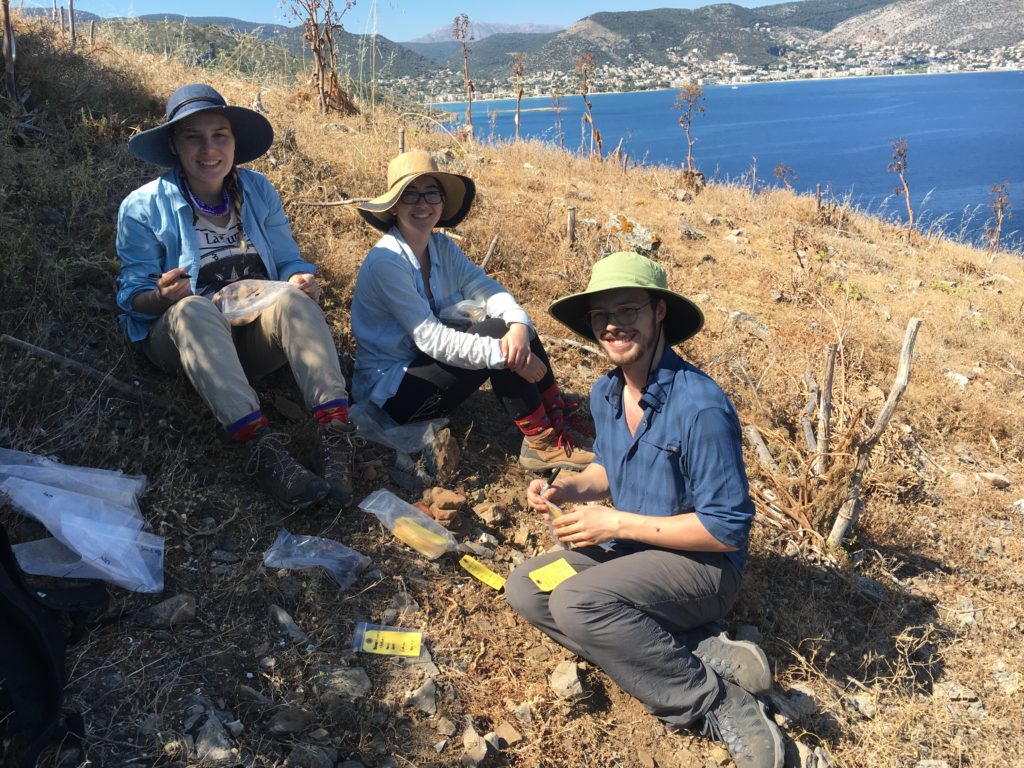

The sea is out: we spent the last day on Raphtis Island last week and the waves are too rowdy again. It’s the final stretch of the survey season. We’ve finished our gridded collection on the Koroni acropolis too, so the first couple days of the week we conduct intensive/extensive hybrid survey. In other words, we “hit the slopes” of Koroni—just beyond the edge of the acropolis site, past the row of boulders that delineated that grid’s border—and extend the size of our units. Instead of doing full coverage like we had in our 20×20 grid squares, we space walkers every 10 meters along the edge of the unit and walk in straight lines across to the other end of the unit at approximately the same pace. We collect along the way anything that lies within our arms reach and make note of the visibility of the surface. At times, the vegetation lying along the slopes is impenetrable, so our lines converge, but we do our best to stay spread out and carefully cover as much of each unit as possible. For many units, the vegetation remains dense, or we run into a cliff, and even when we can manage to walk across the surface in formation, low-lying shrubbery often conceals the ground anyway. But we do our best to collect roof tiles and sherds, and even unexpectedly find a few Mycenaean sherds.

Halfway through the week, we hike back up to the acropolis even though we’ve finished our survey there. It’s time to take a look at the piles of roof tiles we’ve left behind at the corner of each square; we call them “tile piles,” and Dr. Murray shows us the system of “reading tiles” devised by our tile specialist, Dr. Sapirstein. She tells us the difference between Laconian pan and cover tiles and Corinthian pan and cover tiles, which are much more unusual to find, both in our survey area and throughout the Aegean. We go through each pile of tiles and sort the tiles according to categories: Laconian pan tiles are concave, curving gently, whereas the cover tiles have a greater curve to them. Corinthian roof tiles have a very different shape and are often made from a different kind of fabric. Although none of us has dealt with tile analysis in the field before, we learn how to tell the types apart as we work through the tile piles in groups, and Dr. Murray double checks our categorizations before entering them into the database.

We are also busy off the field: in the apotheke, much of the pottery remains to be processed, photographed, weighed, sorted, and generally dealt with. Simultaneously, we have to select, edit, label, and organize digitally the images we’ve taken of these finds, and considerable hours are spent doing this during the day, too. Working through the files of images of our finds from across the last four weeks—snapshots of the novelty of the archaeological world—is a pleasant way to end the season.