Grace Erny is currently a PhD candidate in Classics at Stanford University, previously having acquired an MA from the University of Colorado and a BA from Macalester College. Like Joey Frankl, who you’ll remember from an earlier post, she came to the BEARS project highly recommended as a veteran of the Western Argolid Regional Project (WARP), and valiantly led much of the intensive survey on the Pounta peninsula and Raftis island in 2019. She is now working on her dissertation and anticipating an upcoming move to Athens in August, pending the inevitable visa issues. Amidst all of this important work, Grace generously agreed to spend some time on the less-important task of being subjected to my inane interview questions, from the familiar confines of Stanford Graduate housing in Escondido village.

SCM: You are currently completing your PhD in Classical archaeology at Stanford University. But let’s peer back into the more distant past – how did you get into archaeology and Classics, and what made you choose the program at Stanford?

GKE: I definitely did not come to Classics on purpose – I got there through a love of archaeological fieldwork. When I was in high school, I was very fortunate to do a summer program at the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center. It’s a really great place, a nonprofit in southwest Colorado that does archaeological research and education and works with Native American community partners. They also have a field school where they teach high school students about the Prehispanic Southwest and show them how to dig.

I excavated in a midden – basically a big trash heap – in a Pueblo III settlement called Goodman Point Pueblo, and I found that I loved digging. I was in this trash pile finding stuff – lithics, Mesa Verde Black on White pottery, etc. – and I just thought it was the coolest thing ever. That made me really wanted to study archaeology in college.

The college where I went had one excavation which happened to be run out of the Classics department – a project in northern Israel, Omrit, where Joey also worked. I was actually his first trench supervisor ever, so I’ve known Joey for a really long time!

That’s how I got into Classics – it was really just through the coincidence of wanting to do an excavation and that being where the opportunity was. Before starting at Stanford, I went back to work at Crow Canyon as a full-time field archaeologist. When I decided to do a PhD, I applied to two different kinds of programs: Classics, because I had come to really love working in Greece, but also Anthro, because I also loved working in the American Southwest. Stanford was actually the only Classics program that I applied to.

But I ended up coming to Stanford, partly because I really liked Stanford’s Archaeology Center. The cool thing about the Center is that you can be in a Classics department and do the Classics-y things but there is also a really active and physically connected archaeology community. Also, I was told that if you do Anthro in the U.S. system and you work as an archaeologist in Greece, nobody really understands what you do and it’s confusing for people. Which is too bad – it’s just a stupid artifact of the way the disciplines are split up. But then at the Archaeology Center at Stanford there are two talk series every week with people who work all over the world. Everyone takes a theory class with Ian Hodder, which is a great experience. And I took several other Anthro classes and have an Anthro faculty member on my dissertation committee. So, the program provides a good mix of both things – the Classics training and the literature, but then also the opportunity to work with Anthro faculty and students and learn from their methods and approaches.

SCM: Yeah, that all makes a lot of sense! Digging a trash heap isn’t quite so Vegas as Rob’s early experiences in the buffalo tanks in the Southwest, but it sounds like a stellar opportunity. I agree with your points about the value of the Archaeology Center, too. It is kind of a bummer that archaeology in North America rarely has its own autonomous department. We all end up orphaned in these different disciplines– Classics, Art History – with a lot of people that don’t really understand what we do or what our training is. But at least you have some of these interdisciplinary centers that make a space for archaeologists to come together.

GKE: Yeah, you know how it is in Classics – archaeologists tend to feel marginalized by the philologists and are at a disadvantage in general: we end up having to take all the languages as well as getting trained up in archaeology, which is a big challenge. And some archaeology friends in Anthro departments have told me that there can be a similar dynamic with socio-cultural anthropology and anthropological archaeology, so, yeah – I think it’s good to have a place where the archaeologists can come together and feel like they have a home base.

SCM: We have to take what we can get, I suppose – a refuge from the downcast gaze of the philologists, etc. And Stanford does that better than many places. For sure I think Classical archaeology benefits from having people like you around, who have sought out training in methods and ideas outside the narrow frame of Old World archaeology, so have absorbed approaches from North American archaeology too.

GKE: Well, working in the Southwest definitely made me a much better excavator! When I went back to Crow Canyon before my PhD, we were working on the Basketmaker Communities Project, and it was all dirt architecture. Up to that point I’d only dug architecture with stone walls. But at the Basketmaker III site, the Dillard Site, where we were working, people lived in pithouses that were dug into the ground. You have to pay a lot more attention to the different colors and textures of the dirt, because there is no masonry. I think I dug 30 postholes in one month, because I did all of the postholes in one pithouse. Some were really deep, like elbow deep! Anyway, it was good practice.

SCM: Grace Erny – posthole maestro: you heard it here first! That is certainly a far cry from my first excavation in Pompeii where you knew you hit a floor because…it was a mosaic. Not quite so subtle. It sounds like you really love excavating and have dug a lot of different kinds of places. But I understand that your dissertation is on survey material and how to interpret finds from archaeological surveys. How did you end up landing on a survey-themed topic for your dissertation, and what exactly is the project designed to do?

GKE: I started getting interested in survey when I worked at WARP, which I previously wrote about here. We read all of this stuff in 2014 about survey methodology and the kinds of questions survey is trying to answer, and I found a lot of that reading compelling. And I really enjoyed working on surveys – I’m obviously working on BEARS now.

In my dissertation, I’m focusing a lot on survey data because it turned out to be the best dataset with which to address the questions I wanted to deal with, but it wasn’t really the plan from the beginning. My dissertation is on inequality and social differentiation on Crete in the later part of the Iron Age. There is a lot of work on Crete in the earlier Iron Age, but I’m looking at the Late Geometric to the Classical period, which is a kind of strange period in Cretan archaeology. There is a lot of stuff from the Protoarchaic or Orientalizing period – probably the floruit of the Cretan city-state was in the 7th century – they had some of the earliest written laws, etc. But then in the 6th and 5th centuries there just isn’t that much, and it’s odd because that’s a period when you have a ton of material from other parts of the Greek world. There are also a lot of literary sources describing Crete as a strange oligarchical society that’s very unequal, at least from an Athenian point of view. And I got pretty interested in that idea – was Crete really distinct in terms of inequality?

In archaeology one of the most popular proxies through which to assess inequality is variation in house size across or within excavated settlements. So initially my dissertation was going to look at houses. I started making a huge database of Cretan excavated houses. But I noticed a lot of the houses that we have from this period are located in big, nucleated settlements, and they often aren’t very well-published. Some of the houses that are published are really massive and seem to be end-stage consumers of agricultural products processed elsewhere. That’s what’s happening at Azoria, for instance.

I started thinking more critically about this house size metric as a tool for measuring inequality. At a site like Azoria, where you have four enormous houses that are all the same size and are all full of fancy pithoi, it seems like they are consuming a lot of stuff produced elsewhere. So, you could look at the settlements where the houses are all the same size, and you could say: “Oh, it’s really equal! Everything is awesome! It’s Greek equality! Amazing!” But that wouldn’t actually make sense based on all of the other evidence.

At that point I started thinking about the survey evidence, and how to model the outfield – how could you think about the production side of inequality and the (possibly exploitative) relationships between producers and consumers. Most discussions of inequality are really focused on consumption, so there seemed to be a lacuna there. In terms of the evidence, there has been a ton of survey work on Crete. There have been some attempts to synthesize it for the Minoan and EIA periods, but not much for later periods. So, there was all this data that nobody had ever looked at for these periods. And, with the raw material, there’s also room to do adjustments and refinements, because we’ve learned a lot more about ceramic chronologies for these periods since most of the surveys were conducted in the 80s and 90s. In general, then, I saw an opportunity not only to synthesize previously collected data, but also to go back and revisit some of the survey assemblages, and to bring all that data to bear on this big question of inequality.

What I’m doing now is looking closely at tiny sites in the countryside that most people have identified as farmsteads. I’m digging into what’s actually at those places, whether they are functionally different to one another, how they are related to excavated settlements, etc.

SCM: Wow, that is a really smart, really well-conceived topic and approach. It’s really impressive to hear the narrative there about how the project developed, and that you changed tack when you saw that the data you wanted to use to answer your question wasn’t up to the task. Keeping a flexible, critical mind about how or how not to proceed as you work through the data in that sense requires a certain acute, self-aware intelligence. Other than being the result of your own intellectual and conceptual development, do you think that your project is particularly Stanfordian, or did aspects of the program help lead you to this particular kind of dissertation?

GKE: I took an environmental archaeology course in Anthro with Andrew Bauer, the Anthro faculty member on my committee. He works in Iron Age India. While I don’t use palynology or soil micromorphology or any of those methods in my dissertation, that class helped me think about what survey and environmental studies can tell us about ancient inequality (that’s a big focus of Bauer’s scholarship). So, that was pretty instrumental.

It’s not a specific class, but I have been really influenced by Ian Morris’s scholarship, which of course has changed a huge amount over the decades. I mean, you read Ian Morris from 1987, Burial and Society, and it’s all about synthesizing and analyzing a huge amount of data. I love that book, though I don’t agree with all of it, but I also really like Archaeology as Cultural History from 2000, which is his post-structuralist phase. Let’s say he has gone through a lot of incarnations as a scholar. When I was coming up with my dissertation topic, I thought a lot about Ian’s idea of the “middling class.” He sees a “middling ideology” arising archaeologically in the burial record in the eighth century, and he argues that this foreshadows the development of democracy and an ideology of equality between citizen males in the Classical period.

But that’s a very Athenian thing, and I’d worked on Crete at that point, where the material is so different from the mainland. So, does this middling class thing actually work everywhere, or can we tell a different story on Crete? I’m still working on this part of the dissertation, but I think that the idea of the Classical small-holding farmstead, which looks a certain kind of way on the mainland and in mainland survey, has been integral to the idea of a “middling” farmer class and a Greek ideology of equality. But that just doesn’t seem to be happening in the same way on Crete. I think a lot about Ian’s work – sometimes it seems like I can’t write more than a couple of pages without citing him. He has an article on everything. The project is very rooted in that body of work.

And many Stanford Classics students tend to produce these projects – your dissertation is one example – that synthesize and reinterpret preexisting published work at scale. That is what we’re encouraged to do.

SCM: Yeah, it is not the kind of program where you are going to publish the pottery from Ian’s excavation as your dissertation.

GKE: Absolutely not.

SCM: Now we’ve talked about some pretty heavy work stuff (this is what happens when you get a couple of Stanford Iron Age nerds together!), but let’s now move to the real hard-hitting questions. Something that my colleagues and I spent a lot of time doing at Stanford was sampling all of the burritos in the Bay Area. What about you, do you have a favorite place? Care to weigh in on this important issue?

GKE: This is a pretty hard hitting question! The Northern California burrito is a glorious creation. I grew up in Northern California, so I’ve been eating these since I was a child. My favorite is probably El Farolito in the mission. They have really good burritos. Do you have an opinion?

SCM: I remember eating a lot of burritos and that they were all awesome, but as a rustic Appalachian from coal country I can’t say I was all that much of a subtle connoisseur. I don’t think I have ever met a Mexican food I didn’t like. There was a place near where I lived in Palo Alto that had really spicy chorizo burritos, which I crushed a lot of while studying for general exams. But given that it is Palo Alto I’m sure it’s closed now.

GKE: Yeah, I think everything good in Palo Alto is closed. Even the Nuthouse (the only decent dive bar in Palo Alto and a favorite haunt of Stanford grad students) is closing now!

SCM: WHAT? That is crazy. Let’s not go there: I don’t want to get too emotional. Speaking of Mexican food, I don’t have to tell you that Porto Rafti, where we live for BEARS, has some extremely authentic Mexican cuisine on offer at the world-famous Conga Lounge. Aside from Greece’s best Mexican food, what else about Porto Rafti did you like (or not like) as a place to live and work?

GKE: Every field experience I’d had in Greece before BEARS involved staying in a very tiny village. Porto Rafti is really different because it is a seaside resort situation. I am not going to lie – I did miss the village-y aspect of things. But Porto Rafti is awesome because the sites themselves are so cool and unlike anything I’d ever surveyed before – finding so many lithics, or going to work on a boat! I’d never done that before on an archaeological project, and that was so awesome. I also really liked the house that Rob, Maeve, and I stayed in, which was also the home of our tortoise friend Marina, and the owner Giorgos was so friendly and great. I enjoyed the community.

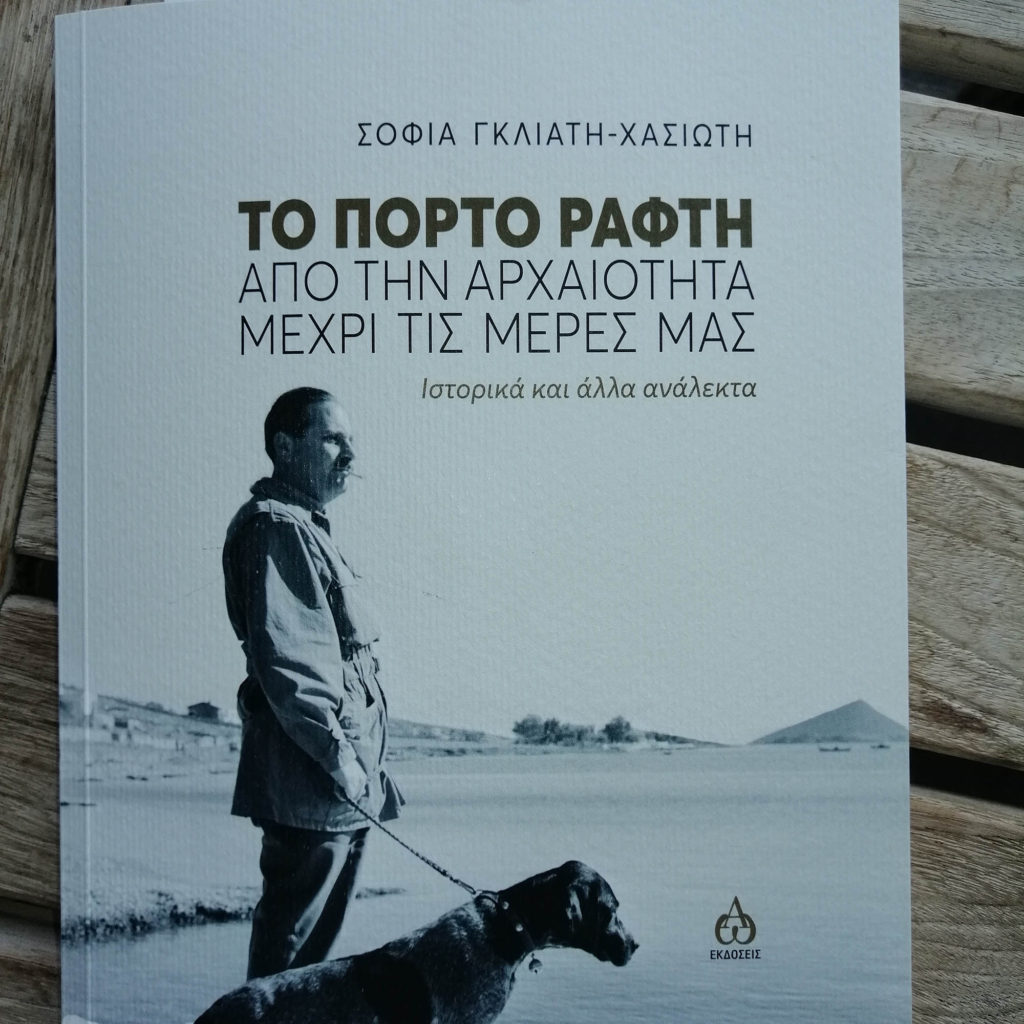

It was also cool to go there because I took Modern Greek for four years at Stanford and the professor, Eva Prionas – whom you also know – has been going to Porto Rafti since she was a kid because her family was Athenian and had a summer house there. I had heard her talking about Porto Rafti all the time, and when I found out your project was in Porto Rafti, I thought that was great, that I could actually go and work in this place I’d heard so much about.

SCM: Yeah, that is funny! I can’t remember that she talked about Porto Rafti back when I was in class with her, but I’m probably just getting senile. I agree that it’s an unusual setting for fieldwork, and kind of a strange town in a lot of other ways. But the Prionas connection is great – we’ll all have to hang out there together someday.

GKE: Yeah, I talked to her the other day! She has a book on Porto Rafti’s history that mentions your AJA article and she was really excited – she was like, “Look! Sarah Murray in the Porto Rafti book!”

SCM: Haha, that’s awesome. I’m famous! I can retire! But, seriously, Eva is great – I am glad that Stanford has someone like that on staff to teach Modern Greek, and that the program encourages people to do that. Now turning to another question about fieldwork. It sounds like you’ve worked on a bunch of really amazing projects with excellent people and superb mentors who’ve provided you with many memorable experiences. Any favorite, most impactful, or most exciting moments that stand out in all those years of work?

GKE: Hmm, that’s a hard question! I’d have to talk a lot about Anavlochos here, the excavation where I work in Crete, directed by Florence Gaignerot-Driessen. That project is just unbelievably amazing. The site is really cool, because you have a cemetery and a sanctuary and votive deposits and a settlement – you almost never get the fully picture of ritual, mortuary, and settlement contexts from one site! It’s like a sampler of all the different contexts you could possibly work in.

Anavlochos also combines the things I like best about survey and excavation. You have to hike a lot to get to the settlement and the votive deposits – to reach the votive deposits, you basically have to do a rock scramble over a beautiful Cretan mountain for almost an hour. So before you do the excavation, you get the survey feeling of wandering up the mountain on the old Ottoman cart road. It’s the best of both worlds.

One of my favorite Anavlochos moments was in 2017. The survey team had found figurines on the surface of one part of the mountain during the previous year. I was digging in this area, in a tiny bedrock crevice, with just one other team member. So we were scraping this crevice and basically hanging over the edge of the mountain. The crevice was just stuffed with Late Minoan IIIC figurines, including a lot of animal figurines like birds and bulls. It was so cool! We kept finding figurine after figurine, and we had to take a dGPS point on each of them, but they kept popping up so quickly it was hard to keep track, so we were using labelled nails to mark their place and then would shoot the nails. It was crazy.

That was my first year on Anavlochos. I had been to the site year before because I had been working at Jan Driessen’s project at Sissi on the coast, and we went up to visit. Florence took us to see the Geometric houses and I just thought: ‘I need to dig here. This is the coolest site I’ve ever seen.’ So, yeah, little LM IIIC figurine-palooza was a real highlight in recent years.

SCM: It’s hard to match that kind of experience! It sounds like such a cool site and a super fun place to work – hiking and figurine deposits all at once…

GKE: It almost wasn’t fair – it was zero work. The deposit was slope wash in a bedrock crevice, so you just brush the dirt off and suddenly, oh, a bunch of figurines!

SCM: I’m thinking about how in archaeology there are people that just seem to have a magical level of good luck, and find unexpected and interesting stuff wherever they go. Hugh Sackett was famous for this – with the Palaikastro kouros, Lefkandi, etc. But it sounds like you might have the magic touch, too.

GKE: That would be cool. I hope that is true.

SCM: You could put it on your CV. Magical Hugh-Sackett type bringer of figurines. Okay, final question. You are about to head to Greece to spend the next academic year at the ASCSA in Athens, which I imagine is exciting. What are you looking forward to about that experience, and what are some of your goals for your stay there – not just necessarily academic goals, but things you might want to do or see in and amongst the many hours of Blegen toil?

GKE: Well, I’m really excited to use the famed American School library. I’ve been inside it, but I’ve never really sat and worked in there. I’ve heard it’s really great. That’ll be nice because Stanford’s library is not great for Greek archaeology, as I’m sure you’ll remember.

SCM: Right. It is kind of all relative though. I didn’t realize how good I had it at Stanford until I went to some other places that really had bad libraries for Greek archaeology. But Blegen Battle Stations cannot be beat, that’s for sure.

GKE: Yeah, I end up Interlibrary Loaning a lot of stuff, so it will be nice to just have it all there.

The main goal is obviously to finish my dissertation. But beyond that, I would like to do a lot more traveling in Greece. The end of the E4 trail runs all the way across Crete, starting at the west end and ending at the Gorge of the Dead, and I’ve hiked the very end of that trail at Kato Zakro, but I think it would be awesome to do the whole thing. That is my number one top rated goal.

Even if that doesn’t happen, I just want to spend some time exploring different regions. One of the things that’s so cool about Greece is that there are so many regions that are distinct from one another. I never did the regular year at the ASCSA, where you do a lot of traveling around. I’ve explored the Peloponnese and East Crete quite a bit, but I’ve never really been to northern Greece, any of the northern islands, or Samos and Rhodes. I’ve never been to Turkey. I’d just like to take a lot of road trips. I don’t know with COVID, but hopefully it will be pretty easy to get around in-country at least.

SCM: That is definitely a good goal! There are so many beautiful and fascinating places to see in Greece, way, way beyond just the archaeological sites. And this is the time to do it, before you get all trapped in the tentacles of a job and tied down with other stuff. Well, I hope it is a year of many triumphs and travels, and that we can talk all about them next summer in BEARS 2021. Meanwhile thanks for this super interesting interview, and good luck with the big move ahead.