This year we are joined by four students from Rhodes College. They have come all the way from Memphis, Tennessee to participate in their first archaeological project! They’ve dove into the work and been a great addition to our team. Here they share some of their thoughts about their experience on BEARS.

Brittany Ashley

Why did you decide to study archaeology and/or art history in college?

In middle and high school, I was on the academic team as the appointed “Arts and Humanities person” which meant I had to study a lot of painters, architects, composers, etc. Somewhere amidst all the memorization, I realized I had a genuine passion for art history and art museums. I especially loved the connections between movements and artists, as well as the impact of historical events on the art of the time.

What is your favorite part of the BEARS experience so far? Do you have a favorite moment to share?

I think my favorite part is best represented by the moment where Miriam Clinton showed us, the Memphians, what our work on Koroni looks like in the GIS program. We saw her connect the dots we programmed with the DGPS and create the structures we’d seen earlier that day in person right there on the screen. Seeing it mapped out like that helped me visualize our work on the surveys as well, how useful it would be to see the quantity and typology of finds as found in different areas, and how that data might be used to interpret the historical usage of this site.

What is your favorite archaeological site or museum that you have visited and why?

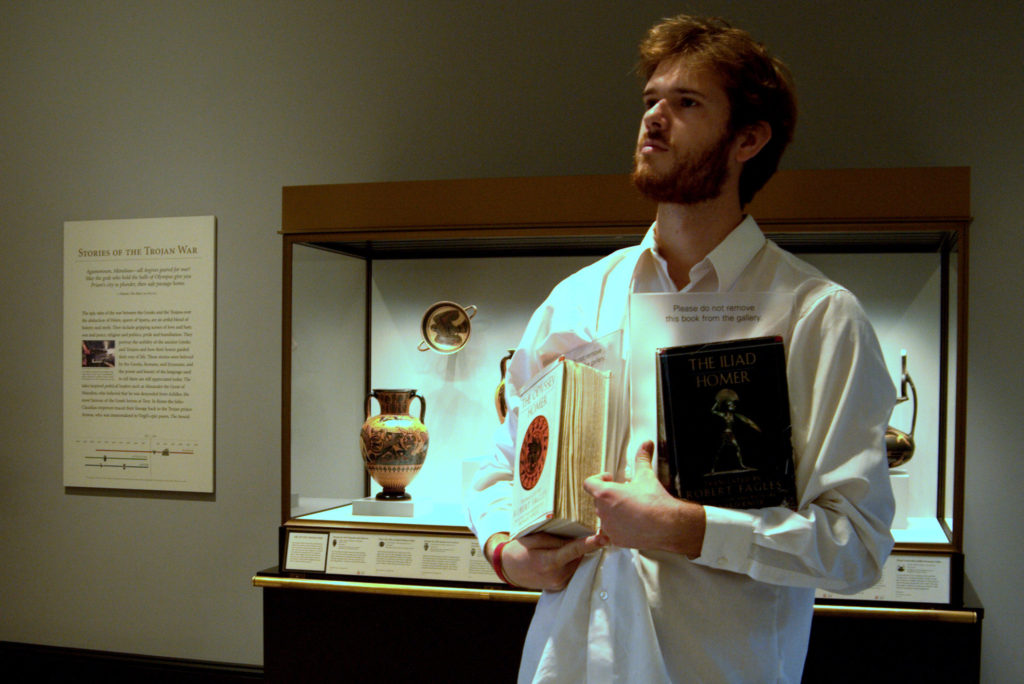

While I have a sneaking suspicion that my final answer will be Delphi once we visit, for now my favorite is Mycenae. The Lion Gate, a staple in all my art history textbooks, was incredible to see in person. It felt like stepping into one of those books and back in time in a way. Not to mention the tholos tombs, especially the Treasury of Atreus which we saw first, and the opportunity to be shocked and humbled by the sheer size of the structure. I’m also interested in the myths of Agamemnon, Iphigenia, and Clytemnestra, so to be at that site in person was cool for that reason too.In middle and high school, I was on

the academic team as the appointed “Arts and Humanities person” which meant I

had to study a lot of painters, architects, composers, etc. Somewhere amidst

all the memorization, I realized I had a genuine passion for art history and

art museums. I especially loved the connections between movements and artists,

as well as the impact of historical events on the art of the time.

Izzy Brewer

Why did you decide to study archaeology and/or art history in college?

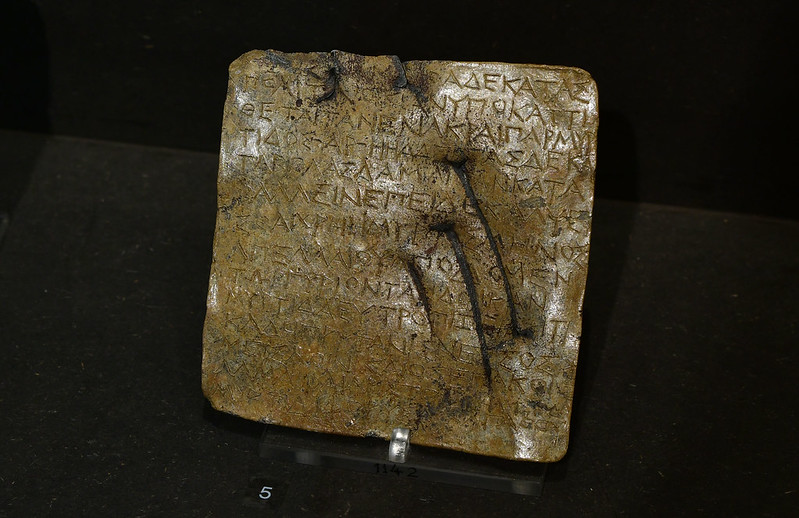

As a kid, I would watch the History and Discovery Channels every Friday night with my dad, and so through that I was exposed to archaeology (or a very dramatized version of it) and casually maintained my interest in it until I started applying to college. I always knew that I wanted to study history but wanted a more hands-on educational experience, and art history and archaeology allowed me to understand history through the tangible evidence people have left behind. I believe working with individual artworks and artifacts that are a direct reflection of the thoughts of their creators is more revealing about the past than just reading texts or looking at history more generally.

What have you found most surprising/unexpected about archaeological fieldwork?

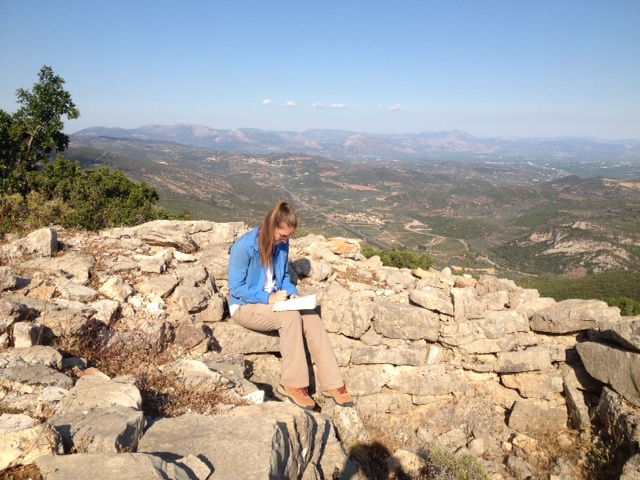

I think the most surprising thing about being in the field is how physically demanding it is, which made me extremely nervous at first because I have almost no hiking or climbing experience (we do not even have hills in Memphis). However, it has made every day in the field more rewarding when I look back and realize that I just climbed a mountain or, in a very specific instance, scaled the side of a riverbed while crawling through thorns and spider webs. The past three weeks have really pushed me out of my comfort zone and taught me that I am more adventurous by nature than I thought I was back at home.

What is your favorite part of the BEARS experience so far? Do you have a favorite moment to share?

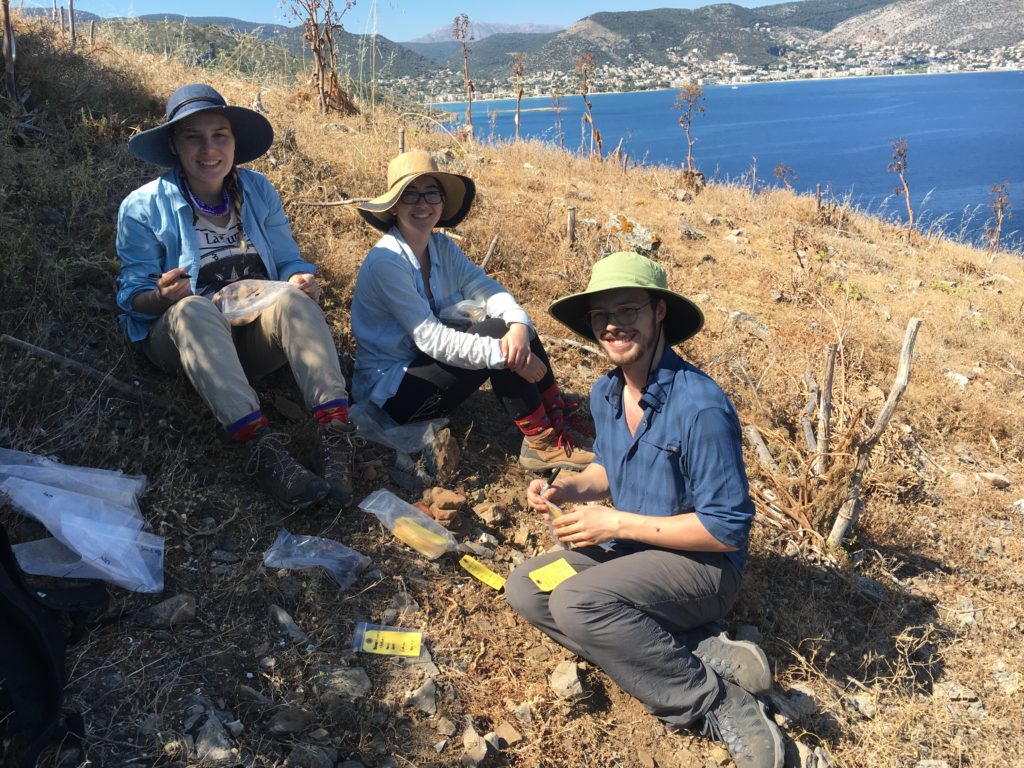

I think my favorite part of BEARS so far has been working with such an amazing team of experienced archaeologists who have gone out of their way to help us learn everything from the basics of conducting a survey to which career paths we should explore based on our specific interests. Everyone has been eager to include us as a part of the group and celebrate even the smallest accomplishments. I have too many favorite moments already, but I would have to say that some of the best are when we are taking breaks and the field and everyone has a moment to talk about the day, share stories, or just quietly enjoy the view in each other’s presence. I am so grateful that this team has been so welcoming to us because it has made the experience so much more meaningful, and I hope that one day I can do the same for the next generation of archaeologists.

Avery Comish

Why did you decide to study archaeology and/or art history in college?

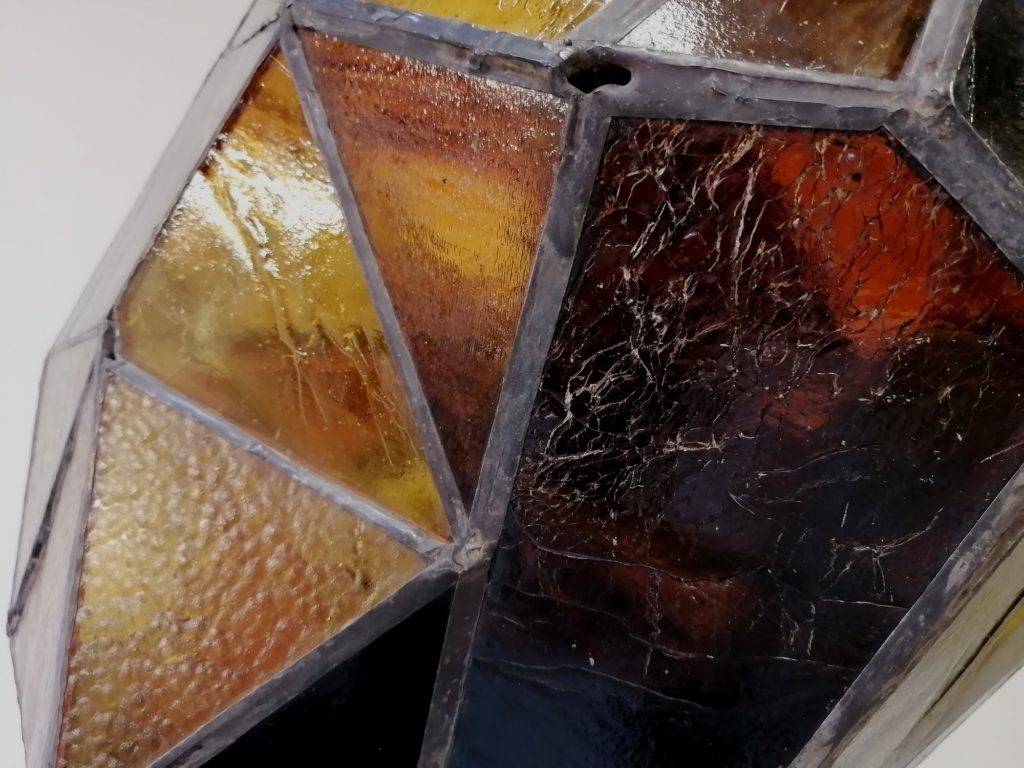

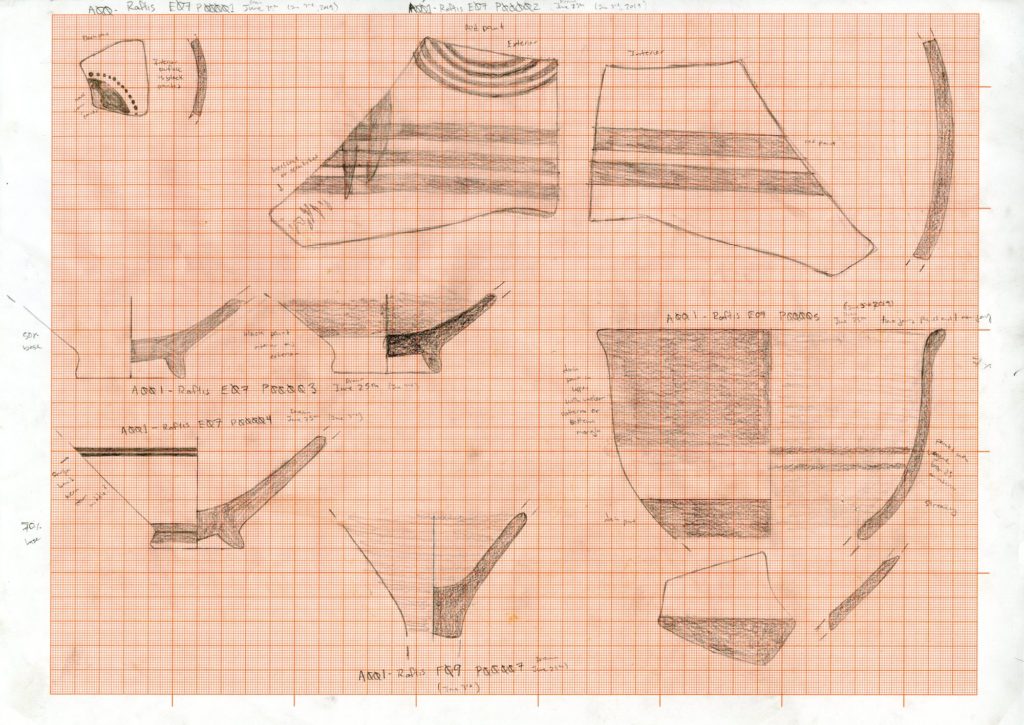

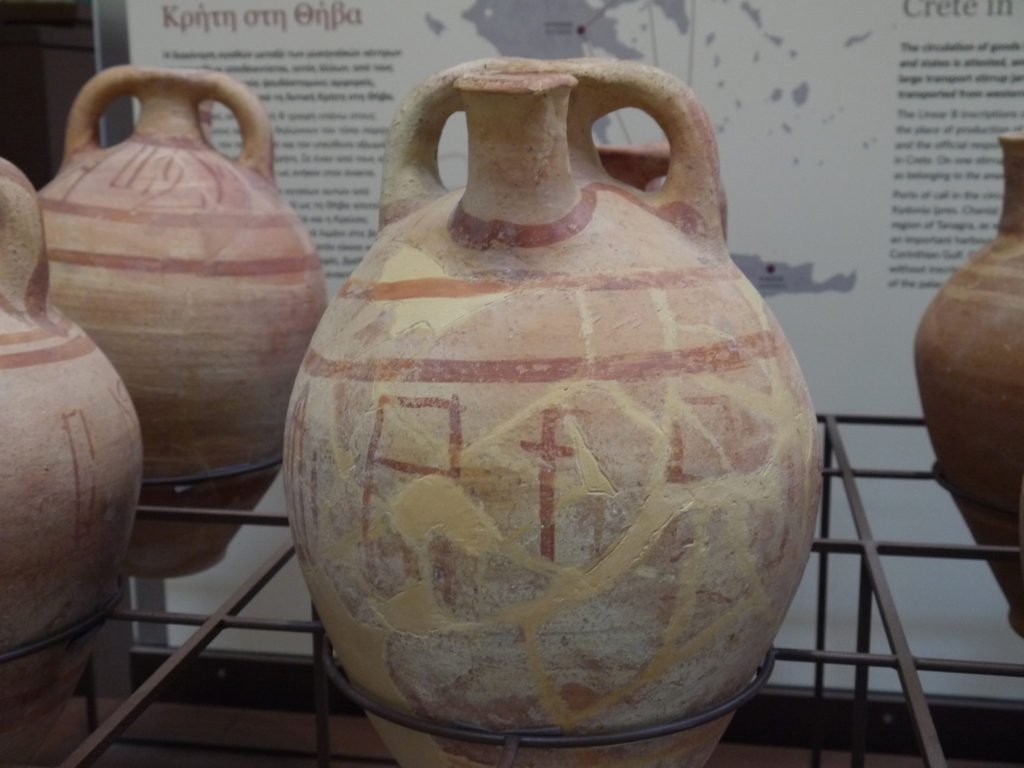

From a very young age, I’ve always had a fascination surrounding art because of the people behind it. Ancient art especially intrigues me because although we can’t always be sure who created a certain piece or built a fortress, we still have a part of that person’s legacy today. Someone hundreds, or even thousands of years ago put time and effort into every piece of pottery or lithic we find. I believe art history, archaeology, and related fields helps form connections to these forgotten people and their legacies.

What is your favorite part of the BEARS experience so far? Do you have a favorite moment to share?

I think my favorite part of the BEARS experience is learning more about the people that might have lived in the Porto Rafti area and (as a tangent to that) learning more about what they left behind. There is almost always something new to discover. For example, on Koroni Kat and I found and mapped a part of the fortress wall that researchers in the 1960’s thought was missing.

What has your favorite survey find been so far?

I think my favorite survey find so far has been a button-like object (that may have actually been used for a loom) that I found on Raftis. I also have been having fun keeping track of the absurd amount of (modern) shoes we find in units. They are never pairs of shoes, just single ones or even just shoe soles? 23 have been found as of June 14th, but I am absolutely sure there will be more. We find them almost every day we’re in town.

Elizabeth Griffin

Why did you decide to study archaeology and/or art history in college?

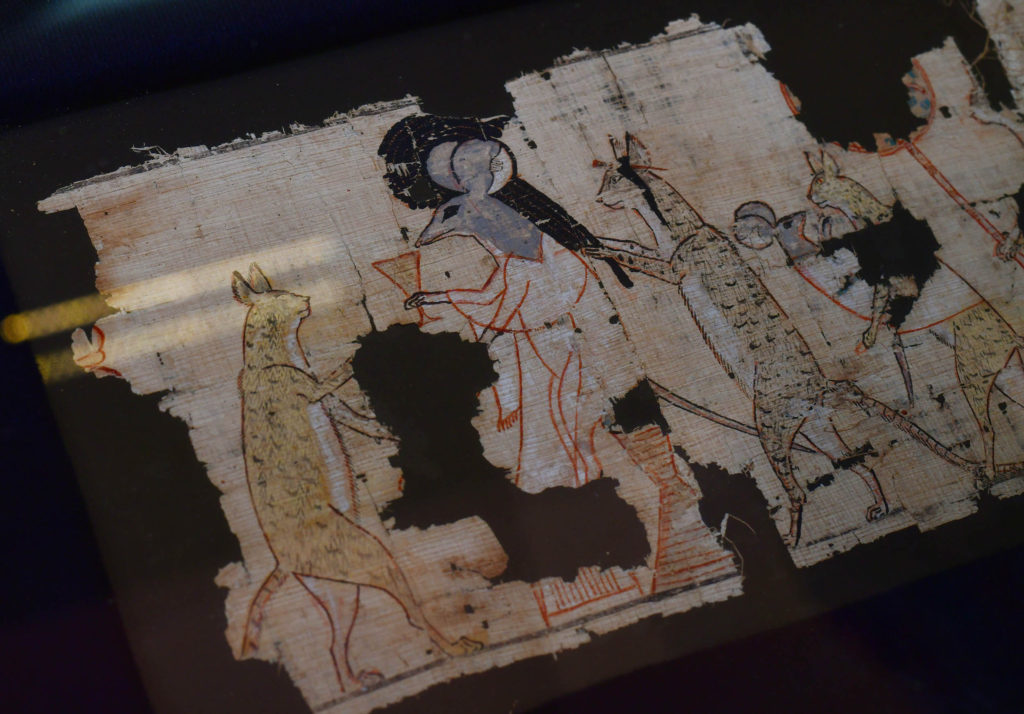

Art and history have always been two of my biggest passions in life and when I was little, I was what they call an “Egypt kid”. When I got to college, I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to major in because I was interested in several different things, so I took classes in English, Anthropology, and classics, and ultimately loved the AMS department at Rhodes. From there, I decided on a focus in material culture that has led me back to my two original loves, art and history.

What is your favorite part of the BEARS experience so far? Do you have a favorite moment to share?

My favorite part about BEARS so far is the people I’ve been able to meet and connect with along the way. Everyone has been so welcoming to us Memphian newbies and have gone out of their way on more than one occasion to talk through everything from grad school stresses to just generally showing us the ropes! Ultimately, the experience has really pushed me out of my comfort zone and helped me to grow into my interests. I’m super thankful to have this experience!