Editorial Note: This post was written by Kat Apokatanidis, a University of Toronto PhD student, about work and an exciting find on the Pounta peninsula.

I cry out in surprise as the wind attempts to steal my hat from on top of my head. Jerking my hand upward I catch it right before it flies completely out of my grasp and hear a whoop of approval from my team leader for saving my hat. It is unbelievable how windy it can get in Greece during the summer. It is late morning and the crashing waves are the only other sound we hear aside from the howling wind. Today it is extra windy, but every day on the Pounta peninsula that juts out in the center of Porto Rafti bay is windy. The wind is inseparable from the experience of working on Pounta, I realise, as my attention is diverted towards the sea where a particularly loud crash emanates from a particularly big wave’s encounter with the rocky coast. I find myself marvelling at the colour the sea takes under the brilliant summer sky as I head on over to the boundary of my unit, clutching my hat to my chest. Sure enough, my other teammates start crying out one by one as the winds try to steal their possessions as well. Some successfully recover their hats, while others watch them sail out to sea; maybe captain Vassilis can pick them up later! At least the wind makes working under the sun more comfortable.

Sighing in slight exasperation at the weather I make sure my hat is securely fastened onto my head, tightening the strap for good measure, and bend back down in search of lithics. The peninsula of Pounta is barren and rocky, devoid of pointy plants and other obstacles that make work at Koroni and on Raftis island so challenging. The finds on the peninsula are also quite different from the assemblages on those two sites – most of the material at Pounta is made of obsidian, a kind of volcanic stone used to make tools. Our job in the grid squares on Pounta is to collect all of the lithics that we see in each unit. And, boy, are there plenty of lithics! Our directors think that the peninsula was the site of obsidian processing in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Ages. Aside from dealing with the wind, working on Pounta is challenging because spotting the tiny bits of obsidian among the other rocks requires careful scrutiny of every inch of gravel. By midday my eyes throb as the blood pressure builds up from constantly bending over throughout the day, trying to separate rocks from other rocks. Opening my water bottle and taking a sip from the thermos I idly look to the ground again, already finding more obsidian. I pick one piece up as I take a bite of my carrot, inspecting it. If you have never seen obsidian before, I would say it looks quite futuristic, its jagged edges shining eerily in the brilliant midday sun even though it’s been sitting on the surface of the earth for thousands of years. The piece, like the others we found, has an air of mystery, as if containing many hidden secrets; before my work in the field I had never thought I would ever gaze at rock formations with any sense of awe or intrigue!

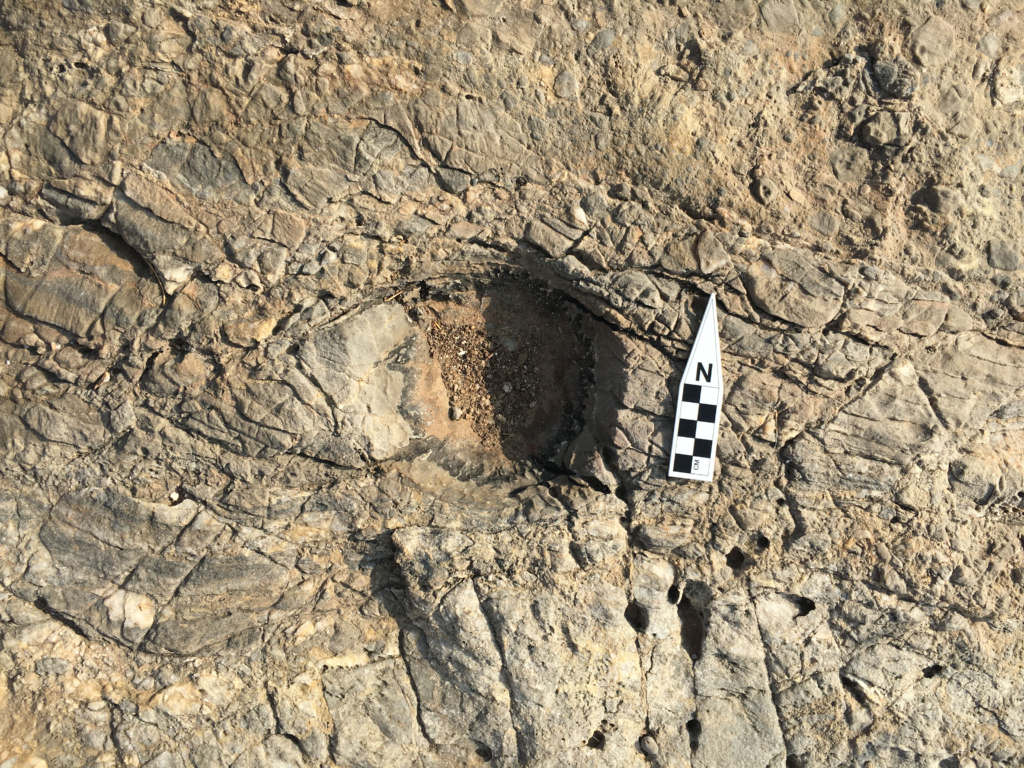

Seemingly the least dramatic of the sites we’ve surveyed in the course of the project, Pounta hides its secrets in plain sight. Much like the obsidian we were there to collect, at first glance the peninsula seems pretty ordinary: just another rocky spit of land issuing out into the blue Mediterranean, dotted with some holiday homes and popular with swimmers and fishermen. Yet, Pounta is a quite extraordinary place. The quantity of lithic material all over the surface is overwhelming, and the other archaeologists on the team say they’ve never seen such a scatter – in most surveys you hardly find any lithics at all. Another surprise came a couple of days into our work there, when we started to notice round holes ground into the bedrock. Definitely not natural and coated in a strange black material, these circular depressions seem likely to have had some kind of industrial use. Who knows what we’ll find next? Surely Pounta will not fail to do what the sites being investigated by the BEARS project do best: surprise us.

Indeed, it is all we could do not to gasp in amazement as the unit produces a small marble figurine. Speculations, theories, and suggestions are tossed about as we each take turns in holding the little figurine. Our discovery of the artifact immediately sparks my imagination. Now my thoughts are consumed with the potential reasons why this figurine came to be deposited on the peninsula, how it might have been lost by its owner, and of course the overall story behind its creation and subsequent use. Was it symbolic of protection against harm? Was it meant as a gift? Almost three weeks into the project, everyone was expecting a lull in excitement, as work at BEARS settled into a familiar routine, but this discovery has everyone caught up in their archaeological imaginations once again. As a newbie, I am consistently told that such excitement is not typical for an archaeological survey. However, as I am caught up in the whirlwind of the project’s activity (and the windy conditions on Pounta) I find myself thinking a less exciting project might not be such a bad thing!