Taylor Stark is currently a PhD Student in the department of Classics at the University of Toronto, where he is a participant in the Mediterranean Archaeology Collaborative Specialization and a burgeoning scholar of the Late Bronze Age Aegean. He is also a founding student member of the BEARS project and distinguished himself with uncanny geospatial skills, among other feats, in the 2019 season. Back home, Taylor is something of a celebrity around the Classics department: he did his undergraduate degree at Toronto and during that time transformed what had been a moribund undergraduate student Classics organization into a thriving community that hosts myriad events through the academic year, and even publishes its own journal. Aside from that, Taylor also has an intimidatingly large and broad bunch of skills and talents, as the following interview makes abundantly clear.

SCM: You are currently pursuing a PhD in the Classics department at the University of Toronto. Can you tell us what got you interested in Classics and why you decided to pursue a PhD in the subject?

TS: It’s sort of a weird story, or maybe weird but also boring? I was gearing up for a music degree in clarinet performance in grade eleven, and I was hoping to play in an orchestra and become wildly famous that way. Then at some point something flipped in my brain, and I decided that I didn’t want to make that hobby into a profession – that would just ruin it all. Kind of out of nowhere I thought, ‘Well, if I can’t make money from music, I’ll go where the money is – Aegean Bronze Age professor!’ And it just sort of emerged fully formed in my head. I don’t have the experience of going to University and then taking a class in Classics and then deciding that’s what I wanted to do. I entered into university explicitly with the aim of ending up in grad school to study the Bronze Age.

SCM: I think that is a very unusual situation, and hardly boring! How did you even know that Bronze Age professor was a thing?

TS: I think it came down to a video game called Age of Mythology that I played when I was young. It was a war strategy game where you played as mythological factions, and I always really loved the Greeks. The game retold in some aspects the story of the Trojan War and I think that must be where it came from at least in a subconscious way.

SCM: So this has been a very single-minded pursuit for you!

TS: It has been. Although I don’t think it made me more prepared for grad school overall. I didn’t exactly use my early intentions to really prepare myself.

SCM: I mean, nobody is really prepared for grad school, are they? I certainly don’t know anyone who was, however early they started to think about it. Do you still play the clarinet?

TS: Very rarely. I was excited to play in a student orchestra here at the very least, but then I realized that would be utterly impossible given the amount of free time I have. It’s sitting right over there, but I haven’t touched it in years unfortunately.

SCM: I’m sure you’ll come back around to it later.

TS: Yeah, maybe in a community band when I’m a real adult

SCM: What, what’s that? A real adult? I’ve definitely never seen or heard of one. You should look into joining up with a Greek band next time you’re over there. All of the bands I’ve seen performing at weddings and festivals in Greece are VERY aggressive with the clarinet, I will tell you that. Bring it along to BEARS next summer – you’ll be an instant star.

TS: Clarinet-playing performance Bronze Age archaeologist! It’ll be a whole new phase of my musical career.

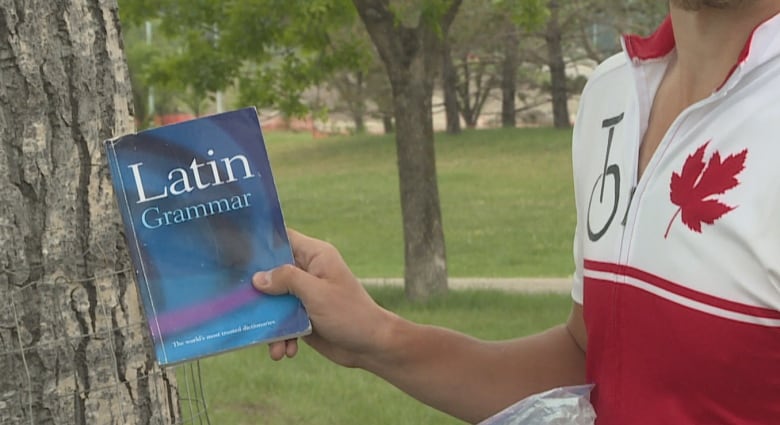

SCM: This sounds very promising. Now, I know you have some other interesting hobbies. You did your undergraduate degree here at Toronto, but I wasn’t around then. When you showed up as a grad student the first thing I learned about you was that you had just unicycled across Canada, and I think you are still the only person I’ve ever met with a serious unicycle hobby. Can you tell us a little bit about the unicycle situation – how you got into it and why you ended up traversing the nation?

TS: I started unicycling when I was nine, so I’ve been riding for quite a while. I grew up in the Rocky Mountains, where I first started out mountain unicycling – anything a mountain bike goes down I’ll go down, but on one wheel. Then when I came to Toronto to do my undergrad degree, obviously, it’s a different environment – there are not many mountains or trails to engage with. I took up urban street unicycling – think BMX or skateboard tricks but on a unicycle. I was doing moves like grinds and flips and jumping off of high things. Then when I finished my degree I wanted to take a couple of years off to work and travel. I had it all worked out in my timelines, but I had a three-month gap in the summer that I wasn’t quite sure what to do with. And a friend of mine jokingly suggested that I ride across the country on the unicycle. And we were like, ‘Haha, that’s very funny! …But wait…what if; is that even possible?’ I started thinking about it a lot more and bought myself a long-distance unicycle and started riding longer distances, and just leapt into it. I knew I had to be in Toronto for the beginning of the Master’s program in August 2018, so I went to Vancouver and just started pedaling!

SCM: Wow, that is pretty wild stuff. I have never seen anyone doing flips on a unicycle but it sounds very daring! Now, I’m not a cycling person, but my general sense is that most people do go for the two-wheeled sort of situation.

TS: Haha, yes, that is the general preference! Really, there’s not much you can do on a bike that you can’t do on a unicycle – other than coast, that is (unicycling requires constant pedaling). I think it works for me because I find unicycling very calming. It requires a lot of focus. When you’re on one wheel, there’s really only one think you can think about – staying on the wheel! Riding helps me clear my head of anxious thoughts and worrying over endless to-do lists. Also, it’s just kind of more fun and unusual, so you get a different type of independent experience that most people don’t have.

SCM: I totally see where you’re coming from. I think a lot of academics go for this kind of thing – being creative and independent-thinking enough to do something outside of the mainstream. I sometimes refer to it as going to the outside lanes of the toll booth – most people are kind of sheep-like and will stack up at the center lanes just because everyone else is doing it and it’s right in front of them, but if you just jerk the wheel over to the far right there’s no line and you get through way faster!

TS: Yeah, for me it just kind of clicked that way. It also made me famous in my hometown, and I got my name out there, which was a benefit.

SCM: So, you started out in Vancouver, and (spoiler alert) you did ultimately arrive in Toronto on the unicycle. Since then you have been knocking ‘em dead in the graduate program here. Where are you now in the program and what kinds of research are you interested in pursuing?

TS: I’m just about to finish coursework. I have a couple of more courses next year to get under my belt and then I’ll start to focus on comps next spring and summer. My focus now seems to be crystallizing around early Greek and Mediterranean society, and particularly looking at peripheral regions outside of well-known states. I’m interested in understanding the experience of people living at the margins of large culturally-influential entities like the Mycenaean state that have been the focus of a lot of research, both smaller state-like entities and groups organized in ways that we wouldn’t even call a state. I’m planning to look at the interactions between large-scale, maybe even imperialist groups, and local communities on the margins, and to think about how those interactions shape local cultural identities. I did my MA thesis on Bronze Age Thessaly and Mycenaean interactions with the ancient Thessalians, and my research is hovering around those sorts of things. I’ve written a paper on Mycenaean interactions in southern Italy. I think all of these notionally peripheral regions are very interesting.

SCM: Those sound like very promising places to poke around for your research focus, and I’m sure it’ll be exciting to get on with it and wrap up your courses in the next academic year. Now turning to fieldwork, before coming to BEARS you (along with apparently everyone else on our team!) worked on another Greek survey project, the WARP project in the western Argolid. Have you worked on other fieldwork projects, too?

TS: Unfortunately, I haven’t yet worked on any other projects. I started on WARP and then after that found myself in a situation where I couldn’t pay for anything else in terms of work abroad during the rest of my undergrad. This summer I was looking into a couple of other projects, and even sent out some feelers about doing more fieldwork after BEARS, but – obviously – those did not pan out! I would like to, and probably should, start trying to get more project experience each summer so that I can experience and learn about different methods and approaches.

SCM: It is not ideal that doing fieldwork is so expensive, which can make it out of reach for a lot of undergraduate students. And I now know that it’s challenging as a director to manage to fund everyone’s flights each summer out of a meagre humanities grant. I actually got dissed on a recent grant application for asking for funding for undergraduate flights – the reviewer thought it should be their problem to get funding or scholarships or something, which seemed crazy to me.

I was thinking about your background and your immense acumen for survey fieldwork – you’re one of these fieldworkers who never gets tired or disoriented, and is always extremely enthusiastic and competent in the field, no matter the conditions. You grew up in the mountains and did quite a bit of mountaineering when you were younger – has that impacted your approach to fieldwork or do you think you enjoy fieldwork especially in relation to that background? Or are those two separate things for you?

TS: I think they definitely interact with each other. I do really love going off the beaten track and just exploring. When I was in the Rockies I always loved investigating weird geological features or caves, or small cool river valleys that are out of the way. It’s also given me a strong sense of direction (cardinal direction, that is) and I can very easily situate myself in a landscape. I think that extends handily to fieldwork. I’ve only done survey, and I think that the far-ranging aspect of survey really appeals to me, especially extensive survey. I really love searching out those nooks and crannies all throughout the mountainous regions in Greece. I also love bouldering: just scrambling all over the place is really fun. Survey work does offer opportunities like that very readily.

SCM: There is some good mountain climbing and bouldering in Greece. I don’t know of other archaeologists who do any climbing, but you could probably check it out at some point.

TS: Yeah, some of my father’s friends have been out to a lot of the islands for climbing. I’ve heard a lot of good things.

SCM: I can definitely see that your background in mountaineering would contribute a lot to your strengths in the field. Are there other aspects of working on a field project that you especially enjoy?

TS: I’d say there are two other things I really love about fieldwork. First, I love being surrounded by people who are both as ridiculous and dorky as myself and as interested in this narrow esoteric topic as myself, but who also have very different approaches. A huge part of archaeology is collaboration. Being able to have really interesting conversations with folks who approach the artifacts we’re looking at in entirely different ways, and can shed whole different lights upon them based on those different approaches, is really fascinating. It helps me to expand my own understanding of the range of approaches.

I also think there is a great sense of satisfaction that goes with proper identification of an artifact. I started out my first project knowing absolutely nothing, and then coming back a second time on BEARS it all flooded back. Being able to step out into the field and pick something up and say, ‘Oh yeah, this is from the Bronze Age’ – I think there is a real sense of satisfaction there.

SCM: Both great points. ‘Archaeology vision’ is very satisfying, almost like having x-ray vision or something – an object I might see as akin to a rock, you understand as this information-laden artifact that tells us all kinds of things about the past.

TS: Exactly, there’s so much information you can glean just from this crumbly piece of pottery. A secret power is a great way to think about it.

SCM: Are there any aspects of fieldwork that you dislike or find irritating, or that you’re always happy to say goodbye to at the end of a project?

TS: Scorpions. I am not a fan of scorpions. I mean, projects can be really exhausting, but I think that’s part of the fun. I usually need to sleep for a good, solid two weeks after finishing a project, but that carries its own satisfaction.

SCM: Yeah, I too usually need a few weeks of quavering in bed like a catatonic lizard, with one of those hamster feeder bottles full of Gatorade installed right next to me so I never have to get up, after five or six weeks of fieldwork. But it is a well-earned, satisfying kind of exhaustion.

TS: So basically, there’s not much aside from the scorpions that I don’t like.

SCM: Sounds like you are in the right line of work! Let’s do a little compare and contrast exercise, inspired by Grace’s post on WARP vs. BEARS: you were on WARP and now you’re on BEARS. Are your impressions of the two projects mostly the same or have they been very different experiences?

TS: There’s an obvious answer available in the sense that the areas and aims of the two surveys are very different. But for me they were also just very different experiences because I was in very different places coming into WARP and coming into BEARS. On WARP, I was just a young undergrad, and in terms of my place in the hierarchy of WARP, I was basically just going along with everything. I wasn’t really privy to a lot of the discussions about interpretation or the methods being used. It was also more of a party atmosphere, at least amongst the youngest of us. There was a lot of ‘Hey, we’re in Greece! We get to let loose a bit!’ going around.

On BEARS, of course, there were always beers – there are always beers – but I think I had more of a sense of place and a sense of focus about the actual research and what I wanted to get out of it. I had more of a feeling that the project at least in a small way belonged to me, because there was a smaller team and we were all part of developing interpretations and plans. Whereas for WARP I was a passive member of the team because of my age.

SCM: Right, right – I’m old enough that it’s hard for me to remember what the heck I thought when I was first doing fieldwork, but you’re right that just starting out you do not have a strong sense of why things on a project are a certain way, or even that there are different ways that things could be done. You’re along for the ride, and maybe focused as much or more on the social aspects. In terms of work, you’re just kind of there as a set of free hands.

TS: Nobody asks you why you’re doing the things you are doing, so you just don’t think about it too much.

SCM: It’s a very cogent point about the fact that your experience on a fieldwork project will definitely vary a lot based on where you are individually when you have that experience, whatever the nature of the project itself. My very first project was in Pompeii and I focused a lot more on drinking beer than questioning the structure or methods at work on the project. I did, however, think critically about how much more I like Greece than Italy, which is why I never worked over there again. Is there anything you particularly like about working in Greece or just spending time there? How about Porto Rafti?

TS: I adore being in Greece. It just feels much more laid back than Toronto. The weather is right up my alley. I know that some people can’t really stand those sorts of intense heats, but that’s exactly where I thrive. I really, really love the food. This summer I’ve been trying to start replicating some Greek food. I made spanakopita the other day. It was nearly there! It had echoes of Greek spanakopita.

SCM: Impressive! That’s a challenging one.

TS: I’m also now learning Modern Greek, so I’m excited to work there next summer, and try to make better connections with people and maybe partake in and understand a bit more of what’s going on.

Porto Rafti was interesting as a place to work. Because it’s a resort town it’s very different from what I’ve seen in other towns in Greece – the lack of a town square, for example – so that was very interesting to work around. But I ultimately really enjoyed it. I think there was a sense of peeking behind the curtain of the tourist impression of Greece. I guess that’s a bit ironic to say given that Porto Rafti is a resort town, but it’s not the kind of place you think about from an extra-national tourist point of view. So, okay, Greece isn’t all about these old stone town squares and the traditional village, there are these other aspects to the country which we should also engage with and appreciate. I liked the idea that Porto Rafti shows us diversity in town structure within this under-nuanced image of a Greek ideal that we take to it.

SCM: That is really interesting observation. I guess we have our ideas about what a ‘real’ Greek town is supposed to be like and all the mystique that surrounds it, but actual reality blows up that simple stereotype. Porto Rafti is in fact a real town, where Greek people spend a lot of time and where lots of people live, even commuting to Athens. It’s a bit weird to knock it as not ‘Greek’ enough because it doesn’t fit into our idea of what that ought to mean.

TS: Exactly. They’re not putting on some façade to meet the expectations of tourists from outside of Greece or look like a postcard. I think it’s important for us as archaeologists to be attentive to the preconceptions we bring to Greece based on some fetish for the past, and to always be engaging with what the place where we work is actually like and what people who actually live there do and think.

SCM: I will say that my emotional relationship with modern Porto Rafti is complicated because it would be much easier to survey there if there weren’t so many beach houses covering up all of the ground! But it will be interesting to see what we can find in and amongst them as we survey in little patches of gardens and orchards throughout the town. The more time I spend there the more I appreciate the place. It has its own thing going on. Also, its non-traditional nature has a lot of advantages for us. In very small villages your team really, really stands out, so you’re kind of under the microscope. But in Porto Rafti nobody even knows we’re there, which gives us much more anonymity, and that makes life easier in a lot of ways.

TS: I think the only people who knew we were there were the owners of our nearest bakery. And they were happy we were there, because we spent a lot of money at that place.

SCM: I am sure they wish you were there right now – but, alas, this summer you gotta make your own spanakopita! In addition to the lack of proper spanakopita, Toronto is maybe not as great of a place to spend the summer as Porto Rafti. But summer in Toronto is not without its charms – any particular activities that you’re looking to enjoy or goals you want to accomplish in July and August?

TS: I just got back from a camping trip and it was really nice to get out of the city for a bit. In terms of academic stuff, the pandemic is a real double-edged sword. Suddenly there is all of this free time, and I feel like I’m pressuring myself to accomplish things I wouldn’t normally have time for. But at the same time, I think the state of the world does impact one’s ability to work. I’m trying not to be too hard on myself. But I have a couple of reading lists that I’ve been going through and a bunch of books I’ve been meaning to read forever. I just read James Scott’s Against the Grain and that gave me a lot of leads on new things I want to read and research.

Something else that I am starting to do, which is probably biting off more than I can chew, is writing a horror novel. I was in South America backpacking around a couple of years ago and I came back with a few vignettes I had written. Suddenly in the shower the other day they just kind of coalesced all together and I saw a way to put them into a coherent story. So, I’ve been outlining that, and threw it all on top of my actual work.

SCM: That is a profound and productive shower! I should probably take more showers. Maybe I’d have better ideas. But writing creatively is a good idea for a way to take your mind off of things for awhile. I always find that writing is one of the only ways to actually take yourself totally out of your own reality. You can forget the rest of the world exists when you get into the writing zone.

TS: Very true – I am hoping that writing something creative and original that I’m producing will help spark other writing too.

SCM: Flexing those writing muscles is useful, no matter what you’re writing. Well, it sounds like you have plenty to keep you busy, so we’ll leave it at that – thanks for taking the time to chat and I’ll keep an eye out for your debut novel on the shelves at Indigo one of these days!