As described in a previous blog post, the BEARS 2020 season was not a very large or complicated initiative: 3 people cataloguing pottery in a museum, and not even all at the same time! So suffice it to say that the scene in Porto Rafti in August was very mellow compared to your average fieldwork season. It turns out that not having any proper fieldwork going on opens up a lot of unstructured free time in a person’s summer schedule. With no logistics of arrival and accommodation to organize, no ultra early mornings spent frantically getting ready for a day out in the field, no students to supervise or worry about, and very few opportunities to stress out about sloppy data management, it’s easy to find time for activities that would otherwise seem impossible to fit in amongst all of the controlled collective bedlam.

Since many of our research questions about the history and archaeology of the Porto Rafti area concern its maritime connections, it seemed like a good idea to take the opportunity to see what the maritime environment of the bay and surrounding waterways was like. I’m definitely a creature of the mountain: most people would be horrified at the idea of someone spending three months in Greece during the summer and never swimming once, but I have achieved this feat many, many times in the last several years! Like everyone else, I enjoy gazing upon the aquamarine splendour of the beautiful Aegean Sea, but that’s about the extent of my usual engagement with the watery portions of the Mediterranean. Before last summer I’d also been on a private boat in Greece exactly once – when I convinced a guy who was in charge of going around collecting trash in a boat at the beach of Balos on the Gramvousa peninsula of Crete to take me around to some of the abandoned islands in that area (I wanted to photograph rusty shipwrecks).

But 2020 is nothing if not a year to reconsider our priorities, and this summer I realized (a) that I really need to swim in the beautiful sea as much as possible! and (b) that it was ridiculous to try to understand the archaeology of East Attica without seeing the region from a ship’s-eye view. Fortunately, Captain Vasilis, who took us to and from Raftis island during the 2019 season, was around this summer and had some time to help out with a few modest sailing trips.

As someone with very little experience of Mediterranean sailing, I was really struck by many aspects of these small adventures, but most of my observations are surely so banal as to be completely uninteresting to anyone who’s gone around in a sailing boat before. I found the experience of time, and the cadence of its passing, at sea to be remarkably different than what I’m used to from traveling around, by foot or car, on land, something that I have a LOT of experience doing. Although from afar the Aegean in the summer usually looks all tranquil and idyllic as a place to be, the actual reality of being in the middle of the sea amidst churning swells and strong currents feels far from either of those concepts. But, I won’t go on about my naive amazement at such basic sensorial aspects of life out amongst the waves.

One observation resulting from sailing out to Euboea and back that seemed of general interest, though, is that the local topography of Porto Rafti is really, really hard to make out from a decent distance at sea, even to someone like me, who has spent years obsessively staring at maps of the area and hiking up to every available terrestrial vantage point. Once you’re in the bay, of course, you can see all of the familiar features, islands, and peninsulas that stand out as distinctive from bird’s eye view. But as we sailed back towards the Attic coast from the east, I struggled even to find the location of the bay – Raftis island and Koroni peninsula largely disappeared into the mountainous background of the interior, and from certain angles I couldn’t even identify the distinctive dragon’s back ridge of the Perati massif. And I have hiked up that ridge nearly a hundred times at this point! Eventually I figured out that the only really distinctive “tell” for the bay’s location was the sharp “beak” at the base of the Mavronori cliffs between Porto Rafti and Kaki Thalassa. Only when we got quite close to the bay’s mouth did the silhouettes of Raftis and Koroni become clear, contrasted against the concrete-villa-speckled amphitheatrical background of the mainland beyond. Surely it would have been more difficult to make them out even at close range prior to modern development.

This made me start thinking about what an advantage this apparent hiddenness might give to people living in the bay – it’s a little bit of a sneaky spot, at least from some perspectives! At the same time, locals often talk about how ships caught in storms in the Petalian gulf are often blown right into the bay, so I guess that might encourage folks to learn to recognize the bay from afar, perhaps as I did using the southern cliffs as a navigational landmark. Anyway, these observations will definitely play a role in our interpretations of choices to exploit the location in different periods going forward.

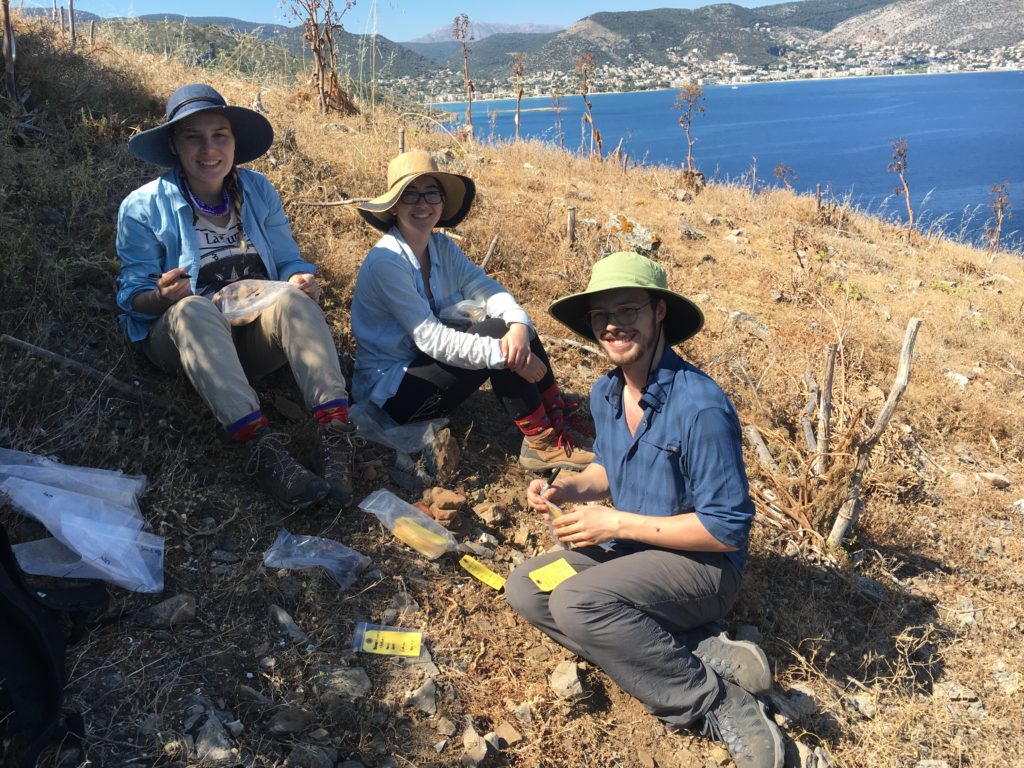

A more explicitly research-focused expedition (at least in terms of the personnel involved!) took place soon after the trip to Euboea. Together with our Attic archaeological colleagues Nikos Papadimitriou and Sylviane Dederix, both of whom are working at the site of Thorikos, we decided to check out the maritime seascape between our survey area in Porto Rafti and the harbour at Lavrio, where Thorikos is located. We are pretty sure that the two areas had some cultural links in antiquity, or at least the artifactual assemblages from the two areas share some interesting characteristics, especially for the Early Bronze and Late Bronze Ages. Some people have even suggested that the prosperity of Porto Rafti in the LH IIIC period (the 12th century) had something to do with control over the metal resources around Lavrio! That seems pretty far-fetched to me, but it certainly makes sense that any link between the two ports would have been more maritime than terrestrial. In any case, we thought it would be interesting for both projects to see what it was really like to sail the route.

The total distance as the crow flies from Porto Rafti to Thorikos is about 15km, and the sail along the coast looks pretty straightforward, although – characteristic of the coastline of Greece generally – the intervening landscape contains many interesting little coves and peninsulas that we figured might make pleasant stops along the way. In the event, the weather was a little heavy on the day we sailed, so none of the small beaches between the two sites were very appealing stopping places, and we just made a direct shot, under sail, with no motor, from the Limani in Porto Rafti town to the industrial environs of Lavrio.

We sailed out of the bay between Raftis and Koroni, then headed straight for the dramatic cliffs that mark the southern terminus of our BEARS survey area – I have clambered up onto these cliffs at least a dozen times, but seeing them from the sea was just as cool as getting sweeping views north and south of Porto Rafti after hiking up to the top.

With Captain Vasilis and his first mate Odysseas, we had a rousing debate about what kind of animal the cliffs most closely resemble. I won’t say what conclusion we reached, so that you can come up with your own independent theories. Aside from their zoomorphic nature, the cliffs look very impressive from below. The geology – gnarly, aggressively folded up metamorphic-type rocks – looks very similar to that which characterizes the understories of the Raftis and Koroni islets, which is not at all surprising given their spatial relationship, I suppose.

Immediately to the south of the great rocks of the Mavronori cliff is an amazingly gigantic unfinished concrete complex, which I hear was supposed to have been a hotel once it was finished. As opposed to the case of the zoomorphic resemblances of the cliffs, there was universal agreement about the beauty of this stately ruin. In general, I have to say that Kaki Thalassa, the toponym for the area south of Porto Rafti, should get a prize for per capita horrendous unfinished modern developments – which is too bad, because the natural beauty of the place is really spectacular. This area is a good reminder that we are truly living in an era that future archaeologists will know as the Period of Infinite Modern Trash.

South of Kaki Thalassa, the next landmark we passed is the Akra Aspro, a collapsing peninsula of impressive white limestone. Apparently it is a popular destination for Athenian rock climbers these days, although it looks like it would be a dangerous place to climb, given that it seems to be shedding boulders on a regular basis. There are also a number of sea caves used by fishermen in the immediate vicinity.

Most of the coast between Kaki Thalassa and Lavrio is characterized by low, barren, rolling hills, almost universally developed with beach villas and small resorts. Many reinforced concrete ‘skeletons’ of houses stand as an eloquent testament to the devastation of the economic crisis of the 2010s, which led to the abandonment of plans to complete second houses due to lack of surplus income. Or at least, that is what my Greek informants tell me. Probably the individual stories are more complicated; sometimes I think it would be interesting to do some kind of systematic study and try to figure out the exact story behind all of these abandoned building sites in East Attica.

Anyway, once we rounded Cape Mavrovouni, about halfway through the journey, we could see the majestic smokestacks of the Lavrio power station! Behold, the fires of industry! Fires of industry are one of my all time favorites.

After we had progressed a bit further south, the site of Thorikos came into view beyond the smokestacks. It’s the distinctive pointy-summited hill to the right of the smokestacks marked in the photo below.

Ultimately we arrived in the bay next to the site of Thorikos in about two hours. It is a very different scene than the one we had departed from so recently – there are many different kinds of industrial facilities all around, and big shipping freighters the likes of which I have never seen up north in Porto Rafti. Despite the somewhat Mad Max-like surroundings, the area is popular with windsurfers, so I guess it probably tends to be windier than the average location along the coast.

The excitement of my colleagues from Thorikos at approaching their site by sea was clear – there was much taking of photos and general speculation about the importance of the peculiar rock formation at the peak of the hill of Thorikos as a navigational landmark for approaching sailors. It is a very distinctive looking hill, and its green ophiolitic boulders stand out quite clearly in the landscape.

After we’d satisfied ourselves with such distractions, we thought about making a traverse over to Makronisos, a currently uninhabited island just to the east of Lavrio that used to be used as a prison for political dissidents, which sounds like a lovely place for a swim, right? However, the sea was angry! As the north winds were picking up Captain Vasilis thought it would be best if we turned to start the trip back towards Porto Rafti, where he knew of a sheltered place to hang out and enjoy some cleaner waters near the bay.

The trip back north was INDEED an adventure! We had to sail a bit farther away from the coast than we did on the way down, because according to Vasilis the chop gets significantly worse closer to the land. The waves were rolling with a vengeance and there was a lot of fun to be had as the prow rose and fell with the swells, making successive dramatic leaps and crashes. The experience was very elemental: the sound of the thwack as the hull slammed into the surface, the cold salt sprays splashing across the deck, the bluster of the northern winds, etc. I think the weather changed somewhat during the course of the day, but the biggest difference was just that we were going into rather than with the wind, which apparently changes everything! It took us about twice as long to get back north as it had to come the other way, and we had to use the motor. Without that, I’m not sure we couldn’t have made it back at all. Yeah, yeah, basic sailor stuff, I know…

After a few hours of being bashed around in the boat, we were happy to relax in the sheltered waters south of Perati island, just to the north of Porto Rafti bay, near Brauron. Everyone had a nice swim, and Odysseas even showed us how he catches octopi – don’t worry, though, we released the baby specimen we found so that it could grow up to become a full size delicious octopus for some taverna-goer in a year or so. As evening rolled in, we headed back home to the harbor, and were relieved to find much calmer and smoother waters in the shelter that the bay provided.

It was cool to see the coastal landscape from a new perspective, and to get to know some amazing colleagues working nearby to our project in East Attica. But spending the entire day on a sailboat is pretty intense! I woke up the next day with a vicious sunburn, even though I’d already been in Greece spending a lot of time outdoors for two months at that point, and a new appreciation for the realities of life at sea. I’d say that maritime travel is both more boring and more exciting than I imagined it might be. I also think I had been underestimating how complicated something simple like a trip from Porto Rafti to Lavrio could be depending on things like the weather and currents. All three of us agreed that there is a lot of potential for future maritime explorations in the future. We hope this will be the first of many reports along these lines, and that there will be opportunities to take the rest of our team members out on the open seas in later seasons.