There’s also a kind of masochistic streak that tends to run through survey archaeologists. If your idea of a good time is sitting on a comfortable chair in the shade eating cookies while you oversee a team of diggers slowly removing loose soil from a habitation surface, you should probably stick to working on an excavation. Survey, on the other hand, almost always requires seemingly ridiculous physical challenges.

It’s Greece in the summer, so it’s going to be hot, and the big agricultural fields that you’re walking usually do not have any shade whatsoever. Sometimes it’s impossible to even find any good shade for taking a break in, so you just pull up the nearest hot, pointy limestone to sit down on for five minutes, and resign yourself to getting your brain blasted by the sun all day long.

The quantity of thorny plants in the Greek countryside sometimes defies belief. Even a seemingly innocuous looking wheat field will be full of some kind of thorny underbelly. It doesn’t matter what you do – at the end of the day of survey you will usually end up feeling, to some extent, like a human pincushion. Sometimes you will survey in uncultivated areas populated by very, very thorny plants, generally known as maquis, which are something out of an evil Disney villain’s imagination. The first survey I ever worked on, around the village of Korfos in the Corinthia, involved walking gigantic units of thick maquis forest, and this was quite an amazing joy for any masochist. Half the time you would be doing something akin to surfing on the plants, suspended five feet above the ground by hundreds of thorn claw hands, like a contestant on a rural Greek version of Double Dare. The other half of the time you were crawling underneath a thicket battling hordes of wolf spiders and moving one limb at a time through the impenetrable shrub. We did not find very much that way, but it was certainly something to do.

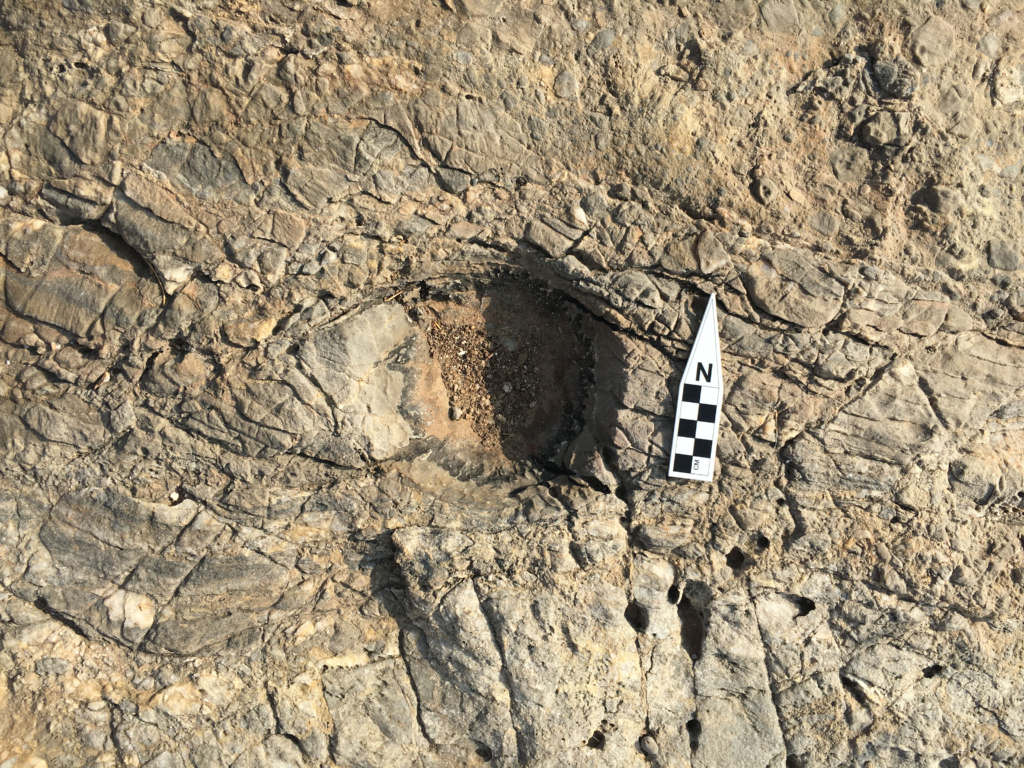

Then there are the funny intellectual challenges that you are juggling along with the physical ones while covered in thorny wounds and sweating your brain out of your ears. At Korfos a lot of what we were doing in our maquis-filled units was trying to find architectural features. But the team could hardly ever agree on whether a feature that someone identified in a unit was a wall or not, so we’d stand there arguing about it forever. And good luck getting your team to keep a bearing on their compass while suspended in a maquis bush, maintain accurate counts of artifacts in 100 degree heat, etc.

Anyway, survey work is pretty brutal sometimes, but there are people like me who love that kind of stuff. I mean, how often do you get to fight through a thorn bush for the sake of knowledge in your normal life? I’d way rather do any of that than sit in the shade eating cookies all the time. Again, I think this is just an issue of constitution. It is often observed that surveyors tend to have a lot in common with goats.