Editorial Note: This post was written by Irum Chorghay, a University of Toronto student, for whom BEARS was an inaugural experience with field archaeology, after the second week of survey.

The waves are unruly this week, so no trips can be made to Raphtis Island. Instead, our team spends the week at Koroni and Pounta, which is a peninsula that divides the Porto Rafti harbor in half. Arriving at this new site, the first thing we notice is the wind. A rusty modern tower stands towards the apex of the strip of land we are to collect in a grid over the next few weeks, and we stand behind it for shelter against the aggressive gales. At Pounta, the visibility is high, and we are taught to look for lithics, and especially obsidian. I pick up several stones to show to Grace, our team lead, before I figure out what to look for: obsidian is a dark grey-black stone, and where it’s been worked, it shimmers. Pounta is a public location, and we conduct survey next to the homes of local Greeks. Somehow, the ground is littered with obsidian anyway.

At Koroni, much is the same as last week: the valley varies in visibility, we find mostly roof tiles and amphora handles, and we log all our findings—as with the other sites—into the database on one of the project’s iPads. In the log, we include sherds collected, roof tile counts and weight, the visibility of the grid, and any other features that we think are relevant. We take a picture of the unit to include in the log and leave the roof tiles behind. The tiles will be revisited, we are told, when a tile specialist arrives towards the end of the survey season.

Once a week, we each get a chance to work at the apotheke, a local museum located charmingly in the middle of nowhere. Here, we soak and clean the previous day’s finds, using brushes for larger pieces and our fingers for painted pottery to avoid scrubbing away its decoration. We recount and re-bag the finds, separate fine-ware from coarse-ware pottery (the former is often a grey-like color, better fired, and simply more delicate, whereas the latter is often larger and heavier), write new labels, weigh the lots, and enter the weights into the database. Because it’s so windy at Pounta, we count the obsidian from that field team in at the apotheke, so that the tiny pieces of debitage don’t fly away into the sea from the site. At the end of the day, we wait for the field teams to deliver new finds. For the most part, cleaning and sorting the pottery is relaxing and feels productive.

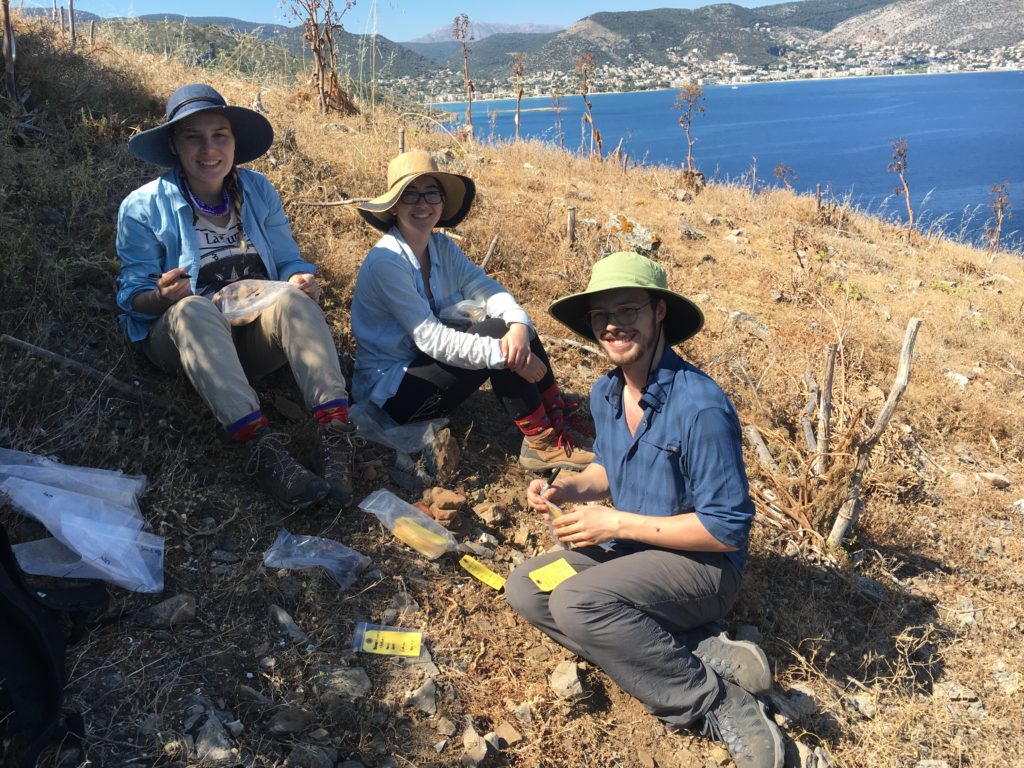

On the last day of this week, Maeve—another team lead—has something exciting planned for the three other undergraduates working at Koroni that day: gridding. Having completed our survey of the Koroni valley, we gather our equipment—a GPS unit, measuring tape, a compass, flagging tape, a sharpie, and a clipboard with the site map laid out—and hike up to the Koroni acropolis. We spend the day mapping out and flagging the grid. We use the GPS to find an approximate point, and confirm the distance with the measuring tape, hoping to capture any errors that the mountain’s uneven topography might yield. The northern edge of the site is marked by a fortification wall and beyond it lies the slopes of a rugged cliff. By the end of the day, I start to feel dehydrated and my teammate twists her ankle; we take a few moments to recuperate under what little shade we find. Sitting on the slope of the Koroni acropolis, looking out to the town stretched out below us and the deep blueness of the water spilling from the land’s borders, we feel accomplished: it’s been a good and hard week!