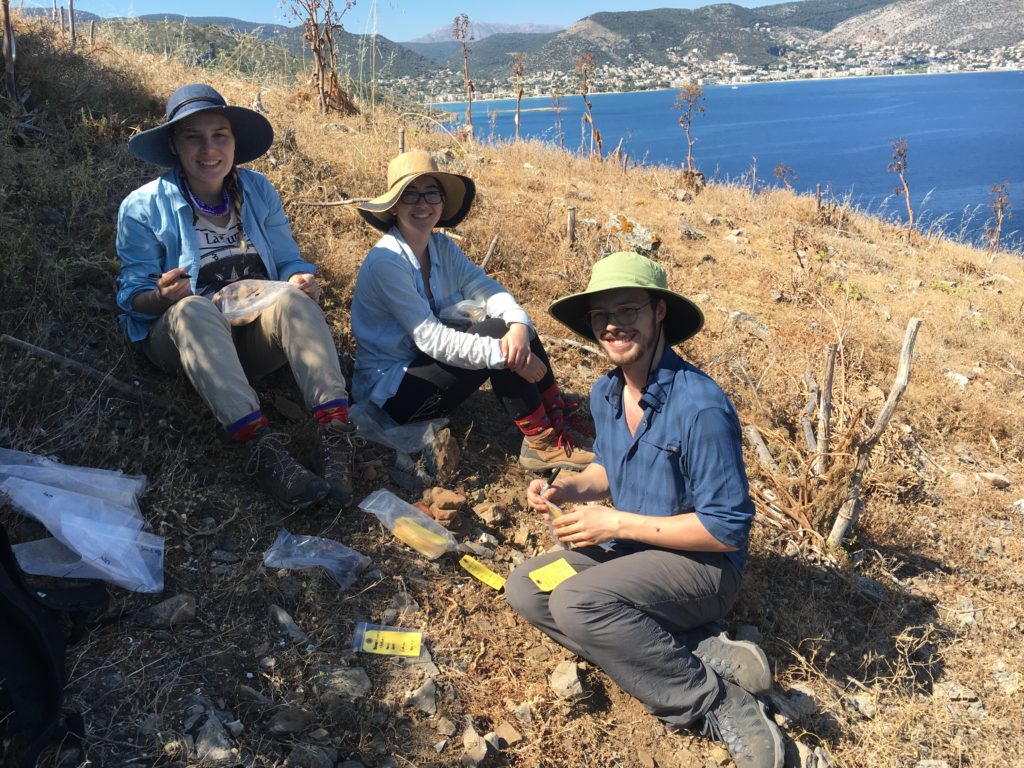

SCM: Ha, yeah, I would always laugh when Denéa called the project an expedition this summer. I mean, we’re like 20 minutes from the airport in a giant concrete resort town…so….it seemed like a funny word to use for what we are doing out in Porto Rafti. Yeah, it’s very different from the normal project where you go to a little village with no internet and marginal mod-cons. In Porto Rafti we have it all – pizza delivery! Third wave coffee! Banks! Anything you want.

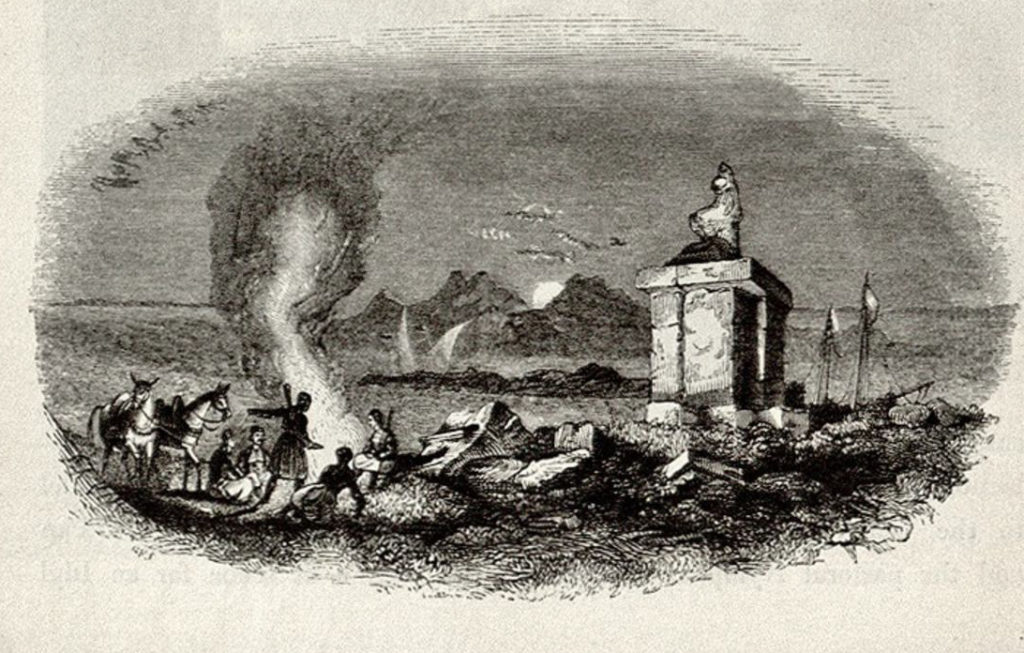

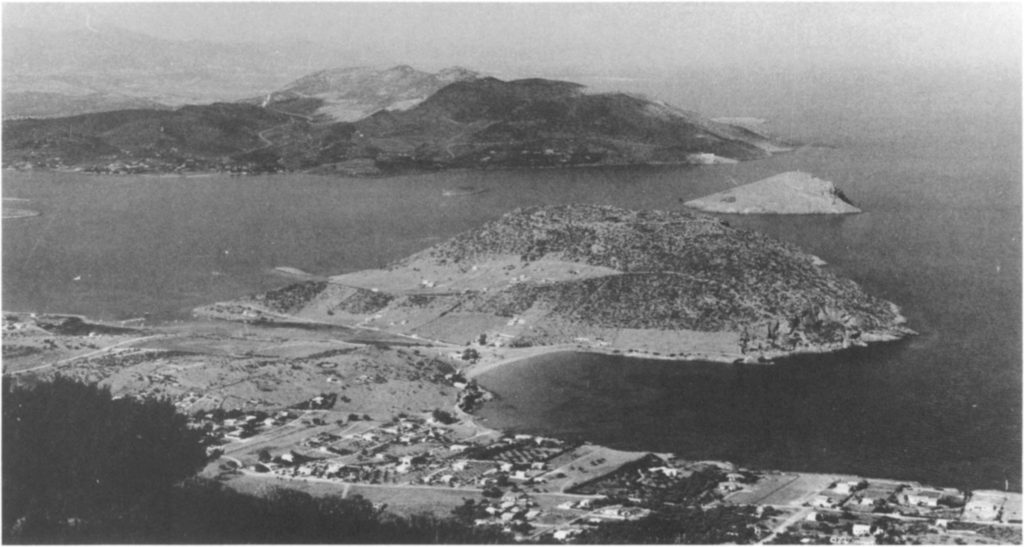

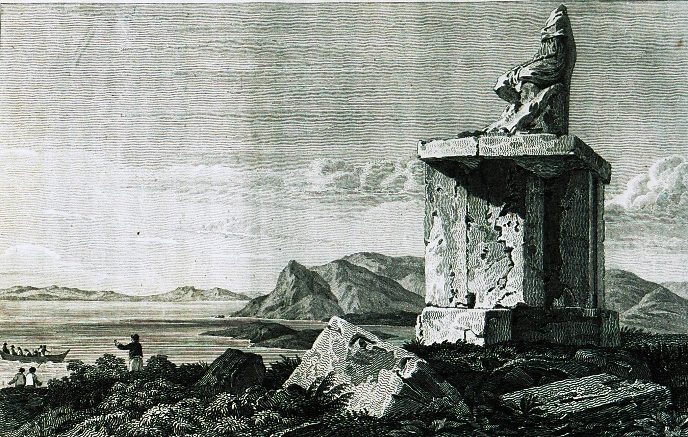

SMD: It is another micro-region, too, though, that I didn’t even know existed before I worked on the project. I’d been to Brauron and we went to Koroni on the ASCSA regular year, but the whole world of the bay had not been on my radar. It’s a bit of a whole little archaeological ecosystem on its own that a lot of people don’t necessarily visit.

SCM: That’s a good point. I spent a lot of time in Greece every year since 2003, but I never went to Porto Rafti once until I thought about starting a project there in 2018. Which is sort of crazy.

SMD: It is funny that it’s kind of off the radar. It’s such a great port and in the middle of everything, so it makes sense that there is so much material there.

SCM: One thing I appreciate about Greece is that there is always more to see. Even after almost 20 years of traveling around all over the place, I continuously find new places and local cuisines and sites and landscapes I didn’t know about at all. Every time I visit I try to purposefully go to one place I have not been, and it’s always a total surprise in the most wonderful way.

SMD: Greece seems very dense. Even from little valley to little valley you often have so much local variation. I enjoyed working in Porto Rafti, even though it is not the most remote. Actually, it was kind of comforting, after not leaving the house basically for a year, to be in a place that was not all that remote or ‘intense’ in terms of a collective living experience. I’m not sure I could have gone from staying in my room all the time to some totally remote village with no internet.

SCM: Right, like when you have a rescue animal that you’ve nursed back to health – you should introduce it back into the wild in stages, or else it doesn’t know how to forage for food or protect itself from predators!

SMD: Exactly. I thought about working on Crete this summer but then I thought – it’s too far! I’m not ready yet.

SCM: Okay, let’s do one more question. In all your travels and project experiences so far, what has been a zany or unusual adventure or misadventure that stands out?

SMD: In college, I took a class on the Odyssey in which we sailed around the Aegean on a boat as we read it – which has obviously shaped a lot of my interests when it comes to research and fieldwork! We had an assignment where we had to write about something that had happened to us during the course but in a Homeric style. So, everyone ended up with these sort of magical realist interpretations of little incidents. My story was about a sort of weird and somewhat concerning interaction with a German tourist when I was out walking alone on Milos. I had borrowed his snorkeling gear and swam out to a shipwreck and then he wanted to talk to me and go back to town, which I was not interested in. But for the assignment I turned it into a much more dramatic story with supernatural elements. I can’t think of a better one. I guess that’s not so zany.

SCM: That’s okay – we are debunking stereotypes about archaeologists waking up unspeakable horrors of the undead and whatnot.

SMD: You carry Ithaca inside you, as they say.

SCM: Profound words!

SMD: I think as archaeologists we feel more comfortable around the dead inert objects of the archaeological record and the landscape, so it’s sort of scary for us to deal with other humans.

SCM: That is true. It is always a little jarring when you think you are alone in some unused landscape, and then you realize there is another human there.

SMD: There is no such thing as a pristine landscape where it’s just you and the god. These landscapes have been actively used forever, and they still are! We’re just guests there.

SCM: Yeah, don’t forget it! A good message for the faithful BEARS blog readers to close out this wonderful interview. Thanks so much for taking the time to share your experiences with us, and all the best for the year in Athens ahead.