BEARS 2021 Production Remains in 3d

During the final week of work of the 2021 BEARS project, Bartek Lis, who was working on the LH IIIC material from Raftis and Praso, very astutely pointed out that the pottery wasters we had collected from Praso were going to be difficult to share with colleagues using 2-dimensional imagery, given their complex and highly irregular geometry. Fortunately our tile specialist Phil Sapirstein also happens to be one of the world’s experts on making highly accurate models of small objects, and he very generously spent a few extra hours in the museum photomodeling a couple of wasters and a piece of what we think might be a Late Bronze Age kiln. Check em out on our Sketchfab account, where a few models of artifacts from the 2019 season live as well.

BEARS 2021: Praso the Great

In the weeks since the last remains of the BEARS 2021 team dematerialized back out into their constituent home coordinates in the ‘real’ world, I’ve spent most of my time communing with the non-human aspects of the project: all of the data, ideas, and photos that we produced during the five weeks of the season. While most members of the team roll off to other projects or activities for the rest of the summer once we finish up, it’s up to the beleaguered director to take care of end-of-season business, from double-checking that everything is in order in the database and GIS to writing up reports and publications detailing the work we did in the field. It’s always sort of sad to bid farewell to the wonderful daily routine of satisfying outdoor work and camaraderie that the fieldwork season brings, but with BEARS that sadness is tempered by the incredible quantity and fascinating nature of the evidence we’ve collected. Both in 2019 and in 2021 it’s been a pleasure to get the old intellectual engine fired up in the aftermath of the season and start trying to figure out what kinds of new stuff we can say about the past based on the season’s work.

This season we spent the majority of our time conducting gridded collection on Praso, the nearest-to-shore and most easily accessible of the four uninhabited islets in the bay. Of course Praso was always one of our targets for survey in the project, but I wouldn’t say it ever loomed large as a big priority. Part of the reason we decided to move Praso up to the front of the schedule this year was because most of our Bronze Age inclined team members were not able to join us due to continuing pandemic complications, and I felt strongly that we should try to “save” the remainder of survey on Raftis (which we already know is a big Bronze Age site) for 2022, when they’ll be back with the team.

In other words, we decided to survey Praso this year because we thought it wouldn’t be all that great or interesting! My idea was partly to kill time while also being productive until the whole team could return in 2022. Praso seemed like a good substitute for Raftis from this point of view – we wanted to stay out on islands as much as possible so we’d be safely socially-distanced from the local community during work; Praso seemed small enough that even with just the six of us that were out in the field for most of the season, we’d be able to finish it all in 2021; and there was supposedly plenty of Late Roman pottery on the surface, which suited our team of mostly non-Prehistorians, especially Joey and Rob, the two project Romanists who made up about 20% of the field team for the first couple of weeks!

Grace already wrote a nice post about the early days of our survey on Praso, so readers of the blog already know that we actually ended up finding A LOT more than just Late Roman pottery on the islet! This was a big surprise, because Praso has essentially zero presence in existing literature. Apparently nobody has really noticed or cared that the density of surface finds on this low-key little spit of land is genuinely astonishing. If we account for limited visibility, our data suggest that many of the 20×20 meter survey squares on the islet contained upwards of 10,000 individual artifacts…far more than what we saw on Raftis, which up until 2019 was the densest, largest surface concentration of material I’d seen in 15 years of survey in Greece!

What’s more, the range of periods represented on Praso is very broad, as Grace noted: it is a very, very diachronic islet. This is notably highly against the trend for the area – the sites we’ve investigated so far have tended to see intense activity, but only in 1–2 periods: Final Neolithic/Early Bronze Age for the Pounta peninsula, LH IIIC & 6th-7th century CE for Raftis, the 3rd century BCE on Koroni. But on Praso there is something from nearly every period that’s represented in the bay overall, from earlier prehistory to Ottoman and WW II era artifacts.

It is a little funny that what is so far the only place we’ve seen around Porto Rafti with consistent human exploitation through time is also seemingly the ONLY place in the area that archaeologists have basically never spent any time poking around. My Bronze-Agey advisors and mentors have all swam out to Raftis islet – long documented to have some kind of LH IIIC pottery presence – and even desolate Koroni islet; there are plenty of little discussions of sherdage and even burials on Raftopoula in various reports. But Praso has somehow slipped under everyone’s radar. Well, except the many people that park their boats next to the protected south side of the island to swim all summer, of course. As usual, the BEARS team had a sort of daily dose of cognitive dissonance, wandering past lackadaisical sunbathers to spend hours and hours laboriously sorting through huge quantities of largely ignored but exquisitely preserved and varied archaeological remains.

Of course, the big question on our minds now is just what was so appealing about little Praso that made it such an attractive spot for people to descend upon from the Final Neolithic to the Late Roman periods.

It is immediately apparent from our survey finds that one of the reasons people spent time on Praso must have had to do with its affordances for craft production – amongst the most unexpected finds from the Praso survey are significant quantities of waste from ceramic and metal production! So far we can’t say too much about the metallurgical activity, since we haven’t been able to do much analysis or contextualization of the slags and ores, etc., but our heads are already spinning with the analytical directions towards which the evidence for ceramic production are leading us. First, it is clear that a regionally important type of LH IIIC pottery was made on Praso – the fabric of the wasters matches the so-called White Ware that is abundant at the cemetery of Perati and on Raftis, as well as at other sites up and down the Euboean gulf. The number of well-documented LH IIIC ceramic production sites in all of the Greek mainland can be counted on one hand, so this is a very rare and exciting discovery. Second, it seems that the many tiles we documented on the Koroni peninsula, dated to the Classical/Hellenistic period, were ALSO being manufactured on Praso. Finally, the same probably goes for the many Late Roman tiles from Raftis. The fabrics of the waste products and the finished products across the sites all match really nicely, at least on first inspection. I had never, ever seen tile wasters in a survey before Praso, but we have collected quite a few – just one of many wild surprises Praso had in store for our little BEARS crew this June.

Suffice it to say that there is a lot to think about as we try to put together the pieces for our 2021 season report. Aside from all of the evidence for craft production, we have the normal embarrassment of finds to deal with –thousands of sherds of well-preserved pottery, a few hundred lithics, plus 300+ “other” objects, including groundstone tools (and even one groundstone vessel!), many Bronze Age figurines, loomweights, lamps, glass, metal objects of bronze, iron, and lead…not to mention a haul of worked, often-perforated terracotta mystery objects that might have had something to do with craft production (or…with the well-documented local tendency of perforating almost everything, which the team knows very well).

One of the appealing parts of archaeology is that you really never know what you will find on any given day or in a given season, let alone from moment to moment. This creates a certain kind of chaos in one’s scholarship, because you might head to a region or a site hoping to find one thing, but the archaeological record has another idea in mind, and then you just have to deal with it. Some find this chaos to be frustrating, but in my experience it has the very salutary effect of keeping your scholarship and ideas dynamic and fresh. For example, when I went to work in the Mazi Plain back in 2014, I was hoping we would find some sites that dated to my major period of interest, the end of the Late Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. Instead there was nothing at all in the plain from the entire period between Late Mycenaean and Archaic – so I ended up spending most of the project obsessively documenting a Late Classical fortification. This ended up constituting several summers of quite satisfying and enjoyable fieldwork, and I learned a lot, both about documenting a massive fortress and about historical fortification architecture!

A sort of funny reversal of that trend, though, seems to be happening for me at BEARS. When I started thinking about working in Porto Rafti my main area of research interest was long-distance trade and exchange in the Late Bronze Age; I was primarily hoping we would recover remains of a settlement associated with the import-rich cemetery of Perati, with the idea that these would shed light on the nature of the region’s engagement with the eastern Mediterranean. However, over the last two years, I’ve become much more interested in the anthropology of craft production, especially thinking about how to reconstruct the roles and identities of craftspeople within society, and much LESS interested in the bigger system of Bronze Age trade. So I guess it is a little bit supernatural-seeming that the archaeological record is being so accommodating in that regard. In addition to lots of cool evidence about trade and interaction, of course, now we have a whole amazing assemblage of craft production remains! Either I’m just really lucky, or karma has something pretty terrible in store for me soon to make up for this serendipitous archaeological turn of events.

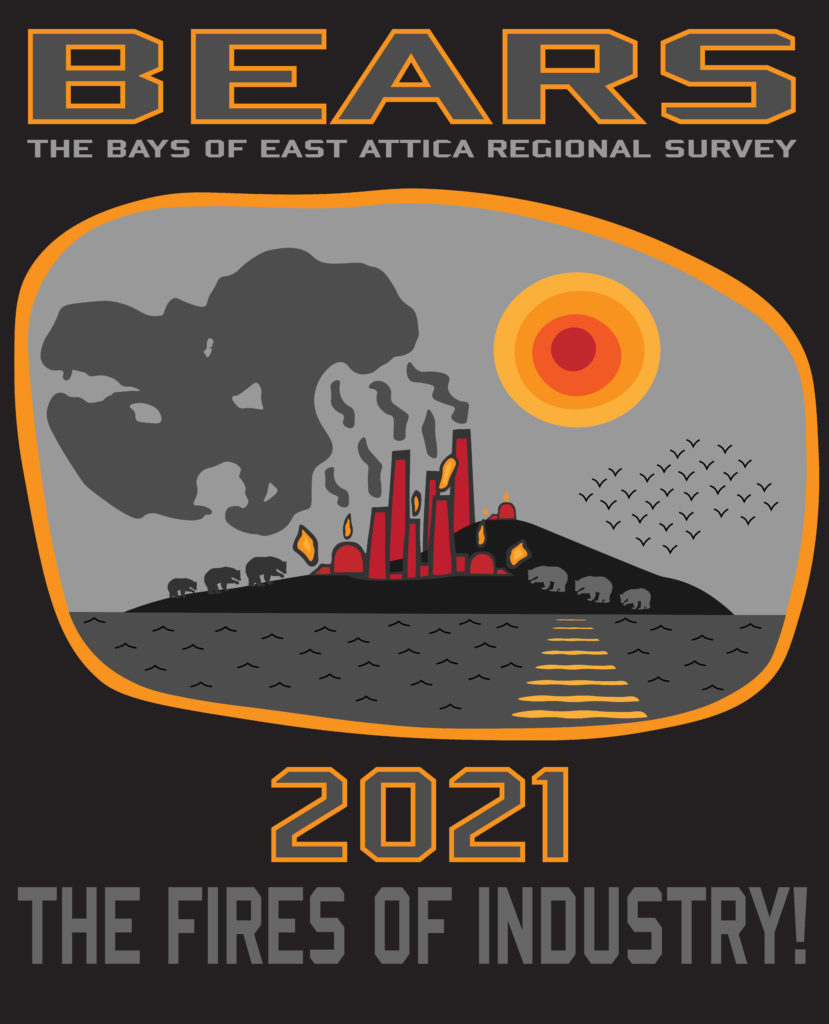

That doesn’t even take into account my other obsession in life – Soviet propaganda art, which of course very often features the most captivatingly semi-hagiographic imagery about the glorious nature of all FIRES OF INDUSTRY. So that has really set me up to be uniquely qualified for designing a sweet BEARS 2021 t-shirt/logo that captures the essence of our discovery on Praso.

Long story short, I can definitely say that Porto Rafti is the best place a person like me could ever could have chosen as a location to run a survey project! We’ll have more to say about the serious sides of interpreting the evidence soon, but for now let us all take some time to bask in the newly-discovered glow of Praso the Great.

Farewell to BEARS 2021

After a final week in the museum spent photographing and cataloguing the many heaps of artifacts discovered in 2021, the final three members of the BEARS 2021 team departed Porto Rafti this morning. Despite all the odds we had a most productive and wonderful five weeks of archaeology: keep an eye on this space for exciting new posts covering the results of the season, additional photos, videos, and 3D models, as well as a new tranche of interviews with recent additions to the BEARS framily!

Speaking of recent additions, this year we were joined for two weeks by Denéa Buckingham, a very talented photographer and film-maker, who doubles as a ambidextrous underwater and terrestrial archaeological fieldworker. She took a whole raft of wonderful photos of the team at work on Koroni and Praso – be sure to check out our updated Photos and Videos page to see what we got up to out in the field this summer.

Back to BEARS: Surveying the Most Diachronic Islet (Praso)

After a series of minor miracles (and careful planning), the Bays of East Attica Regional Survey was able to secure funding and permits for a 2021 field season. Our season will be shorter this year (just four weeks), and many of our key team members were unable to travel to Greece due to the pandemic. On the blog this month, you’ll hear some more about COVID, including our team’s mitigation and safety measures and how the pandemic has changed the way we think about archaeology. We’re also planning some posts that are more typical of a good old field archaeology blog (including a highly anticipated archaeological confessional with our fearless leader, Sarah C. Murray). But, let’s not rest on our blogging laurels; we just finished our first week of field work and there is much to report!

What’s more, the Praso assemblage has shown a very different functional profile than its sibling island of Ratfis. The team has collected several ceramic wasters, slag, and pieces of ore, suggesting that the fires of industry may have roared at various points in Praso’s history. Other finds have included glass, figurines, obsidian and chert lithics, and, of course, abundant combed amphora body sherds. A few days of field collection have only begun to reveal the many secrets of this small and deceptively complex islet.

BEARS 2019 Report Published

The preliminary report of results from the 2019 field season has been published, in the most recent issue (17.2) of the journal Mouseion. The report provides general information about the project’s research goals, a description of our methods and fieldwork, and some early-stage analysis of lithics, Late Bronze Age pottery, and roof tiles, to the extent that we were able to study these materials in 2019. The report can be accessed here, or through Project Muse for those with access through an academic institution.

Maritime Adventures of BEARS 2020

As described in a previous blog post, the BEARS 2020 season was not a very large or complicated initiative: 3 people cataloguing pottery in a museum, and not even all at the same time! So suffice it to say that the scene in Porto Rafti in August was very mellow compared to your average fieldwork season. It turns out that not having any proper fieldwork going on opens up a lot of unstructured free time in a person’s summer schedule. With no logistics of arrival and accommodation to organize, no ultra early mornings spent frantically getting ready for a day out in the field, no students to supervise or worry about, and very few opportunities to stress out about sloppy data management, it’s easy to find time for activities that would otherwise seem impossible to fit in amongst all of the controlled collective bedlam.

Since many of our research questions about the history and archaeology of the Porto Rafti area concern its maritime connections, it seemed like a good idea to take the opportunity to see what the maritime environment of the bay and surrounding waterways was like. I’m definitely a creature of the mountain: most people would be horrified at the idea of someone spending three months in Greece during the summer and never swimming once, but I have achieved this feat many, many times in the last several years! Like everyone else, I enjoy gazing upon the aquamarine splendour of the beautiful Aegean Sea, but that’s about the extent of my usual engagement with the watery portions of the Mediterranean. Before last summer I’d also been on a private boat in Greece exactly once – when I convinced a guy who was in charge of going around collecting trash in a boat at the beach of Balos on the Gramvousa peninsula of Crete to take me around to some of the abandoned islands in that area (I wanted to photograph rusty shipwrecks).

But 2020 is nothing if not a year to reconsider our priorities, and this summer I realized (a) that I really need to swim in the beautiful sea as much as possible! and (b) that it was ridiculous to try to understand the archaeology of East Attica without seeing the region from a ship’s-eye view. Fortunately, Captain Vasilis, who took us to and from Raftis island during the 2019 season, was around this summer and had some time to help out with a few modest sailing trips.

As someone with very little experience of Mediterranean sailing, I was really struck by many aspects of these small adventures, but most of my observations are surely so banal as to be completely uninteresting to anyone who’s gone around in a sailing boat before. I found the experience of time, and the cadence of its passing, at sea to be remarkably different than what I’m used to from traveling around, by foot or car, on land, something that I have a LOT of experience doing. Although from afar the Aegean in the summer usually looks all tranquil and idyllic as a place to be, the actual reality of being in the middle of the sea amidst churning swells and strong currents feels far from either of those concepts. But, I won’t go on about my naive amazement at such basic sensorial aspects of life out amongst the waves.

One observation resulting from sailing out to Euboea and back that seemed of general interest, though, is that the local topography of Porto Rafti is really, really hard to make out from a decent distance at sea, even to someone like me, who has spent years obsessively staring at maps of the area and hiking up to every available terrestrial vantage point. Once you’re in the bay, of course, you can see all of the familiar features, islands, and peninsulas that stand out as distinctive from bird’s eye view. But as we sailed back towards the Attic coast from the east, I struggled even to find the location of the bay – Raftis island and Koroni peninsula largely disappeared into the mountainous background of the interior, and from certain angles I couldn’t even identify the distinctive dragon’s back ridge of the Perati massif. And I have hiked up that ridge nearly a hundred times at this point! Eventually I figured out that the only really distinctive “tell” for the bay’s location was the sharp “beak” at the base of the Mavronori cliffs between Porto Rafti and Kaki Thalassa. Only when we got quite close to the bay’s mouth did the silhouettes of Raftis and Koroni become clear, contrasted against the concrete-villa-speckled amphitheatrical background of the mainland beyond. Surely it would have been more difficult to make them out even at close range prior to modern development.

This made me start thinking about what an advantage this apparent hiddenness might give to people living in the bay – it’s a little bit of a sneaky spot, at least from some perspectives! At the same time, locals often talk about how ships caught in storms in the Petalian gulf are often blown right into the bay, so I guess that might encourage folks to learn to recognize the bay from afar, perhaps as I did using the southern cliffs as a navigational landmark. Anyway, these observations will definitely play a role in our interpretations of choices to exploit the location in different periods going forward.

A more explicitly research-focused expedition (at least in terms of the personnel involved!) took place soon after the trip to Euboea. Together with our Attic archaeological colleagues Nikos Papadimitriou and Sylviane Dederix, both of whom are working at the site of Thorikos, we decided to check out the maritime seascape between our survey area in Porto Rafti and the harbour at Lavrio, where Thorikos is located. We are pretty sure that the two areas had some cultural links in antiquity, or at least the artifactual assemblages from the two areas share some interesting characteristics, especially for the Early Bronze and Late Bronze Ages. Some people have even suggested that the prosperity of Porto Rafti in the LH IIIC period (the 12th century) had something to do with control over the metal resources around Lavrio! That seems pretty far-fetched to me, but it certainly makes sense that any link between the two ports would have been more maritime than terrestrial. In any case, we thought it would be interesting for both projects to see what it was really like to sail the route.

The total distance as the crow flies from Porto Rafti to Thorikos is about 15km, and the sail along the coast looks pretty straightforward, although – characteristic of the coastline of Greece generally – the intervening landscape contains many interesting little coves and peninsulas that we figured might make pleasant stops along the way. In the event, the weather was a little heavy on the day we sailed, so none of the small beaches between the two sites were very appealing stopping places, and we just made a direct shot, under sail, with no motor, from the Limani in Porto Rafti town to the industrial environs of Lavrio.

We sailed out of the bay between Raftis and Koroni, then headed straight for the dramatic cliffs that mark the southern terminus of our BEARS survey area – I have clambered up onto these cliffs at least a dozen times, but seeing them from the sea was just as cool as getting sweeping views north and south of Porto Rafti after hiking up to the top.

With Captain Vasilis and his first mate Odysseas, we had a rousing debate about what kind of animal the cliffs most closely resemble. I won’t say what conclusion we reached, so that you can come up with your own independent theories. Aside from their zoomorphic nature, the cliffs look very impressive from below. The geology – gnarly, aggressively folded up metamorphic-type rocks – looks very similar to that which characterizes the understories of the Raftis and Koroni islets, which is not at all surprising given their spatial relationship, I suppose.

Immediately to the south of the great rocks of the Mavronori cliff is an amazingly gigantic unfinished concrete complex, which I hear was supposed to have been a hotel once it was finished. As opposed to the case of the zoomorphic resemblances of the cliffs, there was universal agreement about the beauty of this stately ruin. In general, I have to say that Kaki Thalassa, the toponym for the area south of Porto Rafti, should get a prize for per capita horrendous unfinished modern developments – which is too bad, because the natural beauty of the place is really spectacular. This area is a good reminder that we are truly living in an era that future archaeologists will know as the Period of Infinite Modern Trash.

South of Kaki Thalassa, the next landmark we passed is the Akra Aspro, a collapsing peninsula of impressive white limestone. Apparently it is a popular destination for Athenian rock climbers these days, although it looks like it would be a dangerous place to climb, given that it seems to be shedding boulders on a regular basis. There are also a number of sea caves used by fishermen in the immediate vicinity.

Most of the coast between Kaki Thalassa and Lavrio is characterized by low, barren, rolling hills, almost universally developed with beach villas and small resorts. Many reinforced concrete ‘skeletons’ of houses stand as an eloquent testament to the devastation of the economic crisis of the 2010s, which led to the abandonment of plans to complete second houses due to lack of surplus income. Or at least, that is what my Greek informants tell me. Probably the individual stories are more complicated; sometimes I think it would be interesting to do some kind of systematic study and try to figure out the exact story behind all of these abandoned building sites in East Attica.

Anyway, once we rounded Cape Mavrovouni, about halfway through the journey, we could see the majestic smokestacks of the Lavrio power station! Behold, the fires of industry! Fires of industry are one of my all time favorites.

After we had progressed a bit further south, the site of Thorikos came into view beyond the smokestacks. It’s the distinctive pointy-summited hill to the right of the smokestacks marked in the photo below.

Ultimately we arrived in the bay next to the site of Thorikos in about two hours. It is a very different scene than the one we had departed from so recently – there are many different kinds of industrial facilities all around, and big shipping freighters the likes of which I have never seen up north in Porto Rafti. Despite the somewhat Mad Max-like surroundings, the area is popular with windsurfers, so I guess it probably tends to be windier than the average location along the coast.

The excitement of my colleagues from Thorikos at approaching their site by sea was clear – there was much taking of photos and general speculation about the importance of the peculiar rock formation at the peak of the hill of Thorikos as a navigational landmark for approaching sailors. It is a very distinctive looking hill, and its green ophiolitic boulders stand out quite clearly in the landscape.

After we’d satisfied ourselves with such distractions, we thought about making a traverse over to Makronisos, a currently uninhabited island just to the east of Lavrio that used to be used as a prison for political dissidents, which sounds like a lovely place for a swim, right? However, the sea was angry! As the north winds were picking up Captain Vasilis thought it would be best if we turned to start the trip back towards Porto Rafti, where he knew of a sheltered place to hang out and enjoy some cleaner waters near the bay.

The trip back north was INDEED an adventure! We had to sail a bit farther away from the coast than we did on the way down, because according to Vasilis the chop gets significantly worse closer to the land. The waves were rolling with a vengeance and there was a lot of fun to be had as the prow rose and fell with the swells, making successive dramatic leaps and crashes. The experience was very elemental: the sound of the thwack as the hull slammed into the surface, the cold salt sprays splashing across the deck, the bluster of the northern winds, etc. I think the weather changed somewhat during the course of the day, but the biggest difference was just that we were going into rather than with the wind, which apparently changes everything! It took us about twice as long to get back north as it had to come the other way, and we had to use the motor. Without that, I’m not sure we couldn’t have made it back at all. Yeah, yeah, basic sailor stuff, I know…

After a few hours of being bashed around in the boat, we were happy to relax in the sheltered waters south of Perati island, just to the north of Porto Rafti bay, near Brauron. Everyone had a nice swim, and Odysseas even showed us how he catches octopi – don’t worry, though, we released the baby specimen we found so that it could grow up to become a full size delicious octopus for some taverna-goer in a year or so. As evening rolled in, we headed back home to the harbor, and were relieved to find much calmer and smoother waters in the shelter that the bay provided.

It was cool to see the coastal landscape from a new perspective, and to get to know some amazing colleagues working nearby to our project in East Attica. But spending the entire day on a sailboat is pretty intense! I woke up the next day with a vicious sunburn, even though I’d already been in Greece spending a lot of time outdoors for two months at that point, and a new appreciation for the realities of life at sea. I’d say that maritime travel is both more boring and more exciting than I imagined it might be. I also think I had been underestimating how complicated something simple like a trip from Porto Rafti to Lavrio could be depending on things like the weather and currents. All three of us agreed that there is a lot of potential for future maritime explorations in the future. We hope this will be the first of many reports along these lines, and that there will be opportunities to take the rest of our team members out on the open seas in later seasons.

BEARS 2020: Small but Mighty

Like most everything associated with archaeological research, our carefully laid plans for a 2020 field season of the BEARS survey derailed spectacularly sometime around late March. In Toronto, the spring that followed was cold and grim in pretty much every imaginable way.

However, by early July, virus cases had waned to vanishingly small numbers in many parts of Europe, and Canada had gotten the pandemic situation sufficiently under control that Canadian residents were among the few non-EU passport-holders allowed to enter the coveted Schengen zone.

Even after it became clear that Canadians could in theory travel to Greece, we never considered trying to hack together a late-summer season of fieldwork with students or whatever archaeologists happened to be hanging around Athens or anything like that. However, we did have the idea that, since we’d found an unexpectedly large amount of material in 2019, it would be useful if we could at least get a tiny skeleton crew to spend some time in the Brauron museum working through our backlog of finds, so that everything would be up to speed heading into 2021. Although most folks ended up not being able to travel to Greece at all, or in time, we did manage to get three BEARS team members on the ground to work on cataloguing and study of our finds from 2019 this past August (no Goldilocks, unfortunately). The purpose of this post is to provide an update on the very tiny BEARS 2020 project, such as it was.

Skeleton season BEAR #1 was me, yer faithful blog correspondent and project co-director. After a week of scuffling with Air Canada agents (even as a person with Canadian permanent resident bona fides, it sure is not great to be traveling on a US passport these days) and the acquisition of official-looking transit papers from the extremely helpful Greek consulate in Toronto, I flew to Athens on July 11. Coming on the heels of 4 months of barely leaving my apartment, the trip felt majorly miraculous. My first priority was to get up into the mountains for some cobweb-shaking-off hikes among the big peaks of the Pindos, which took a couple of weeks. Once that was out of my system, I settled into Porto Rafti and Brauron to get down to the business of bulk cataloging finds from BEARS 2019.

In addition to a whole series of forms containing information about survey units, the BEARS database integrates two finds catalogues: one for inventoried finds and one for bulk finds. I know databases are not the most exciting topic for blog posts, so I won’t go into too much detail about the many wonderful intricacies of the forms. The idea is that every single object collected in the survey is represented/accounted for in the bulk finds catalogue and given a bulk finds number, while only select objects (say, sherds that are very well-preserved, very datable, etc.) are pulled out, given an inventory number, and described/analyzed in more detail.

Our finds experts are the ones who will ultimately go carefully through the pottery from each unit and make the decisions about which finds should be inventoried, since they are the ones who are trained to know which sherds might be especially informative or important. Cataloguing bulk pottery is not quite as sensitive a task. The idea is to produce a comprehensive log of finds from a unit, so that someone can look at the form for any individual survey unit and get an immediate sense of its finds: how many krater rims or kylix stems, what distribution of sherds from different periods, fine wares vs. coarse wares, etc. To me it also seems just generally desirable to have a specific number attached to every find from the survey, however worn or seemingly uninteresting, from the point of view of Stackenblochen principles.

In practice bulk cataloguing involves trying to impose some kind of informational order on the chaos of a bag of unsorted sherds: sorting coarse and fine wares, separating out different kinds of feature sherds (bases, handles, rims, etc.) or sherds that all come from the same vessel shape, that kind of thing. Then each sherd or group of sherds is given a lot number and entered into the bulk catalogue, along with basic information: shape, fabric description, etc.

Since our small 2019 lab team was overwhelmed just keeping up with basic processing of all of the finds we brought in from the field, literally zero bulk cataloguing was done last summer, which is not so great, since we collected over 6,000 sherds. I lost a fair amount of sleep over the winter thinking about the sorry state of our finds catalogues, to be honest. In a way it was really helpful to have 2020 “off” from fieldwork so that there was time to catch up.

Unfortunately, I am also the last person that anyone would want to be tackling this activity. This summer was the first time that I’ve spent any time whatsoever working on finds in the lab, and I felt very fish out of water getting into it and trying to make sense of our many, many large bags of pottery. It turns out that it is helpful to have, say, at least a basic grasp of the vocabulary that ceramicists use to describe things like fabrics when cataloguing thousands upon thousands of survey sherds.

Fortunately, I was joined in the first week of August by Skeleton Crew BEAR #2, Bartek Lis, who drove/ferried down from Poland. Bartek knows more about pottery, especially LH IIIC pottery in our region, than pretty much anyone. He’s also been restudying the pottery from the neighboring Perati cemetery, so he is definitely the Mycenaean ceramicist that we need to have studying our Late Bronze Age material. I also happen to have been friends with Bartek for almost my entire adult life – he is one of the very first people that I ever met on a Greek archaeological project, in fact: back at Mitrou in 2004. I learned an immense amount from working with him in the museum, and he was able to get me up to speed on the basic characteristics of our Raftis assemblages pretty quickly. It was a great reminder that even elderly people like me can learn some new tricks occasionally. Now I can identify a piece of a krater rim or a deep bowl handle, and even some of our local fabrics like white ware and the normal Raftis cookware, without thinking about it too much. This was very helpful when sorting all of the finds from Raftis, because, oh boy, did we collect a lot of deep bowl handles out there.

Bartek was obviously not just in town to help me figure out how to describe bulk finds. Much more of his time was spent analyzing the sherds he’d inventoried last year in more detail and pulling out new finds to be inventoried. He found some amazing and surprising stuff; we have lots of really interesting new insights and questions about the Raftis assemblage just from his short visit this summer, and there are still many units he did not have time to get through. But I’m not going to spoil all the fun by saying too much about those finds just yet.

Alas, someone as skilled and awesome as Bartek is always in high demand, so after a week of work revealing many new mysteries and secrets of Raftis pottery, he was off to Volos. Following a lonely week of manic cataloguing, I was joined for the last two weeks of August by BEARS Skeleton Crew member #3, Melanie Godsey. Melanie is a PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill who is studying our Classical and Hellenistic pottery, especially the Koroni finds, amidst a multi-year stretch of living and working in Athens at the American School of Classical Studies. She worked on Koroni for her MA thesis and study of the pottery from old excavations on the site will form part of her PhD thesis, so she is, like Bartek, really The Person that we want dealing with the Koroni finds from our survey. And, like Bartek, she was very generous in sharing her expansive knowledge about how to identify and date historic pottery, especially amphoras, with a very ignorant project director. In just 2 short weeks she powered through all of the Koroni finds from 2019 and produced a detailed report of her conclusions: this was quite an excellent development, since we didn’t really know much about those finds at all before her visit in 2020. Melanie also happens to be excellent company, and I was glad to have a friend around for early morning swims and even the occasional evening beer and nachos.

By the end of the season, our tiny team of three accomplished quite a lot – after one more week of photography and data entry in early September I’d completed the bulk pottery catalogue, which now includes every single sherd collected in 2019, and Melanie and Bartek had inventoried over 400 objects from Raftis and Koroni.

Although it was cool to have a new experience, I don’t think I’d want to spend five weeks sorting pottery again: as a creature of the mountains, being in the museum all of the time made me feel pretty weird and cagey. Somehow it was even more tiring than working in the field, too – now I understand why the lab teams need so many coffee breaks.

Aside from yawny museum days, there was plenty of time to get outside and enjoy the beautiful environs of eastern Attica, too. The hours of the Brauron Museum dictated our work schedule, so outside of 9–4pm Mon–Fri a person was free to roam. I got into a good daily routine of running every morning around sunrise, and then swimming in the sea for awhile before work. This is the view in morning light from my usual swimming spot at the south of town:

Not a bad way to start the day. In the afternoons I’d usually hike around for a few hours, either on the trails atop the Perati massif to the north and the Mavronori cliffs to the south, on Koroni, or off-piste in the mountains southwest of town, between the bay and the archaeologically rich area of Merenda (now home to the world’s most elegant and harmoniously sited hippodrome). I met a few very handsome foxes, and accumulated an extensive collection of photos of Porto Rafti from nearly every possible direction. Overall I would give the summer’s swimming and hiking achievements a solid 5 stars. Last summer, in contrast, I only swam twice, if you can believe it, and I met zero foxes.

Another great development this summer was that we began seeding closer relationships with some other colleagues and projects working nearby in Attica, especially the Belgian/Greek project currently underway at Thorikos. Nikos Papadimitriou hosted Melanie, roving tile consultant Phil Sapirstein, and me for an incredible tour of the site, and also showed us some of the cool finds they’ve been pulling out from Stais’ leftovers the Lavrio museum. We all learned a lot. The following week I recruited our friend and boat captain Vasilis Miliotis to take some of us on a sail from Porto Rafti to Lavrio and back so that we could get a sense of the maritime route between the two sites. Of course, there was some afternoon boat swimming as well. This is an excellent method of forming collegial relationships. I recommend it to everyone!

All in all it ended up being one of the most enjoyable summers that I’ve had for a long time. It’s always the best to be in Greece under any circumstances, of course, but I certainly appreciated it more this year because it seemed for a long time like we might not be able to travel at all. It was also a much more relaxing schedule than normal, since pretty much everything was canceled and there weren’t too many people around. I mean, we did get a lot of work finished that really needed to get done on BEARS; and much work was done generally, outside of hiking and swimming hours. But usually there is so much going on and so much to do that you hardly take the time to just stop worrying about dumb work stuff and enjoy the many succulent pleasures of summer in a glorious place.