Hibernating BEARS

As winter descends in earnest and our team members look ahead to a long, dreary season of hunkering down at home (at least that seems to be the way things are heading here in Toronto), it seems like a good time (in line with what I hear is a major holiday down south of the border) to remember how lucky we are to have such a Number One Top Rated team of students and collaborators on the BEARS project, not to mention how fortunate we are to have the chance to work as archaeologists in Greece full stop. Whatever happens in the next couple of years, at least we’ll always have heaps of fun memories (and obsidian, and LH IIIC pottery, and data about rooftiles) from 2019.

For now, it seems like an opportune time to figure out how to actually hibernate for a few months. Someone wake us up in April when the snow melts and we’ll figure things out from there.

A Lecture about Postpalatial Raftis

BEARS fans might be interested in tuning into a lecture about the project’s work on Raftis island, which will take place on the evening of Tuesday October 27th. The talk is for a local historical society in Marietta, Ohio, so it will be aimed at a general audience. Anyone can register to watch online via this link.

Update: If you missed the lecture and would like to watch a video recording, it can be accessed here (with a suggested donation to the sponsor, a small non-profit organization offering historical programming in the small Appalachian community of Marietta).

A Lecture by Catherine Pratt, BEARS co-director

Members or fans of the BEARS project might be interested in an upcoming lecture by our very own co-director Dr. Catherine Pratt. The lecture is taking place Thursday October 22 at 4pm Eastern time as part of the University of Toronto’s Mediterranean Archaeology Collaborative Specialization speaker series. Here is a link where you may register to attend via zoom.

BEARS-related content in the newsletter of the Hellenic Museum of Melbourne

If the onset of fall weather and the excessive workloads of online teaching have got you down, why not take a break by reading some of the unhinged thoughts and ramblings of a BEARS project co-director? Here is an interview that was recently published in the newsletter of the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne, Australia.

Update: Photos of Rob’s Armenian Haircut

Faithful readers of the BEARS blog will recall one of many entertaining anecdotes recounted by Rob in his genre-defining BEARS interview from early June, in which he had an exciting haircut adventure in Armenia. Just down the pipeline for those who were left wanting more are these documentary photos of the haircut in question, thanks to Chris Cloke and Emily Egan, who were present when it all went down.

The Mesogaia and Porto Rafti: a couple of historical notes

Here are two minor tidbits about the modern history and culture of the area around Porto Rafti as we eagerly wait for additional team member interviews and contributions to materialize:

(1) Mesogaia, land full of drunks?

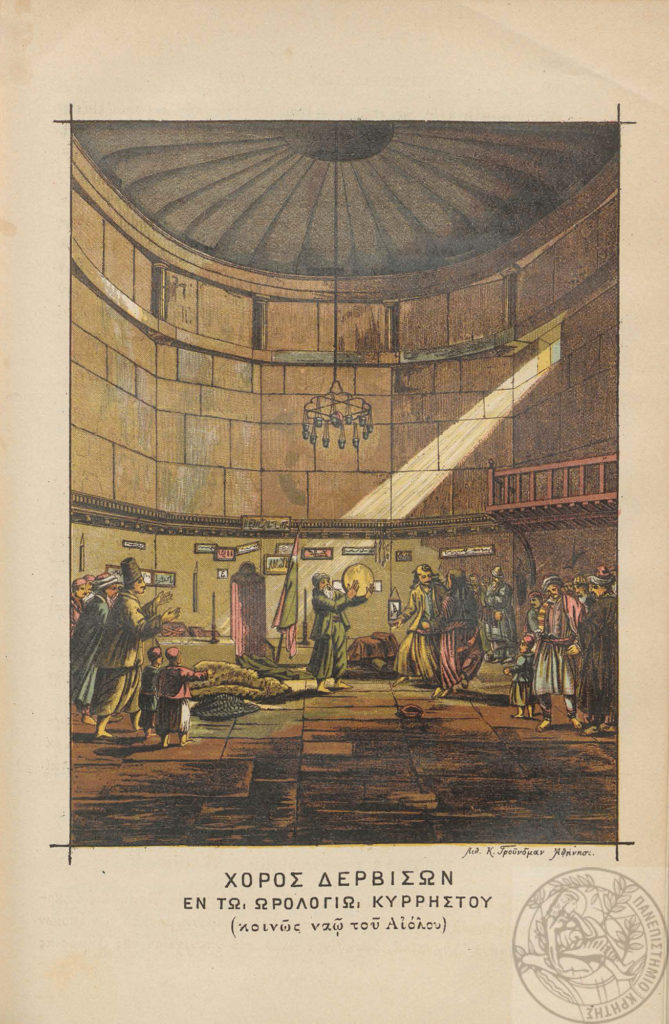

This winter I was reading some old accounts about eastern Attica and ran across a three-volume book on the history of the Athenians that was published by an (amateur) Athenian historian and nationalist named Dimitrios Kambouroglou in 1889. Kambouroglou was interested in the non-ancient history of the city and its inhabitants. The book is mostly focused on describing folk traditions and life ways of people in different parts of Athens and Attica during the period of Turkish rule (the Tourkokratia).

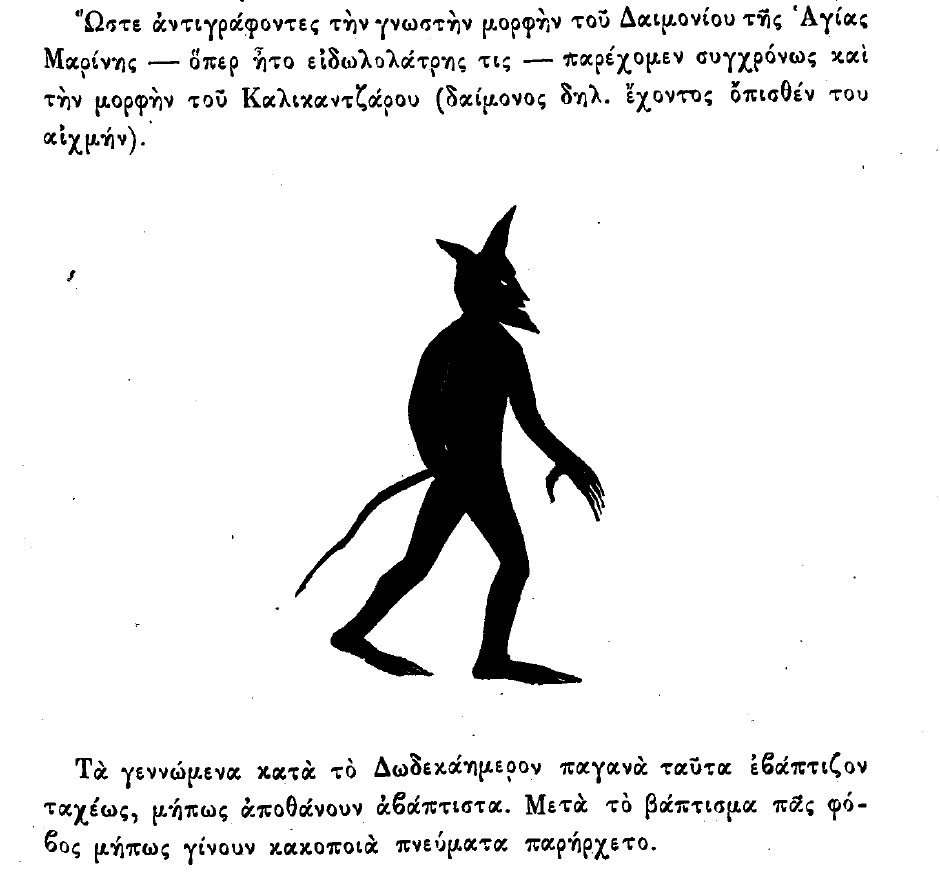

The book is pretty strange, and you can learn a lot about old customs in there – for example, I learned that during the Turkish period in Athens, you were supposed to put a bunch of salt in the first bath of your baby, in order to make sure it would grow up to become a nostimos anthropos. There is also a fair amount of useful advice about avoiding various evil spirits.

Kambouroglou was a member of the urban elite, and you can tell: there is a strong contrast presented between urbane city-dwellers and the marginal (Albanian speaking) populations of Attica outside of the urban center. His book includes a long aside on the villages in Attica outside of Athens, and the Mesogaia is singled out as particularly degenerate, especially because of all of the wine that is produced and consumed there. When discussing the Mesogaia, Kambouroglou opposes the attractive, hospitable, and subtle urbanites and the rowdy, unrefined Albanian speakers of the Mesogaia, who he thinks should be classified somewhere on the spectrum between human and animals. He calls Athens “the city of pnevmatos” – that’d be a reference to a spirit/reason in the sense of the noble, civilized, Hellenic way. The Mesogaia, on the other hand, is “the countryside of oinopnevmatos” – implying spirit in a drunky, wino kind of way. According to Kambouroglou’s account, back in the day everyone thought that the Mesogaia was a land of boozy degenerates. I suppose the joke is on Kambouroglou now, since the region is full of successful wineries that offer popular agriturismo-type accommodations and elegant tasting rooms.

(2) Return of the Exiles from Gyaros in 1974

One of my goals from the winter was to wrangle together a body of archival imagery from Porto Rafti, but mostly this effort has not gotten very far. It’s something I’ve been working on a little this summer. One interesting photo that has turned up is this image of exiled Greeks returning from the island of Gyaros subsequent to the fall of the military junta that governed from 1967–1974. Gyaros is an island to the northwest of Syros that was used as a prison and place of torture/abuse for communists and dissidents thought to be a threat to the dictatorship. The photo shows a large crowd of people meeting a ferry at the Porto Rafti limani. The still mostly undeveloped slopes to the north of the bay and the familiar silhouette of the Perati massif are visible in the background.

Insect Companions of Mediterranean Survey

An underappreciated aspect of archaeological fieldwork in the Mediterranean is that it brings a person into intimate contact with a lot of weird insects. Everybody knows that the Mediterranean is an ‘artifact-rich’ landscape, positively bustling with forgotten old ruins and dense scatters of ancient pottery and lithics. But when wandering through the underbrush or digging holes in the ground out there, a keen observer will also notice a microscopic world teeming with strange and awesome life. They’re not quite as flamboyant as the chest-sized moths and gaudy, florescent ‘disco bugs’ one frequently meets in the jungles of the Amazon, but – like it or not – we are surrounded by a lot of insect companions when we go a-traipsing about in the Mediterranean.

In reviewing the wondrous world of archaeology insects, I’m going to leave aside the whole butterfly situation. Butterflies are among the most visible and superficially beautiful of the insects of the Mediterranean, but there are just too many kinds of butterflies all over the place to do them any kind of justice here! They come in all shapes, colors, and sizes, and if you are patient you can get some stunning photos of them in the spring when they are suckling greedily from the blooming flowers and will complacently pose for you.

Obviously, once you get into butterfly territory you’ll necessarily be seeing some strange caterpillars out there too. The best one I’ve seen is a blue and orange striped species in the Vikos gorge in Epirus, but there are some very fun spotted ones around the Peloponnese too.

After last season, all of the members of the BEARS project are very aware that spiders are quite common in the Mediterranean countryside. I sometimes feel bad about how many elaborate and carefully spun spiderwebs that we smash through when doing survey. I guess in a way it’s a kind of community service, since getting caught in one of those things spells certain death for some of our other insect friends, like grasshoppers. But, you know, predators are gonna predate! It’s nature’s way!

One of the most entertaining survey bugs, and not coincidentally one of the most evil, is the common horsefly, or as I call it: Evil ‘Stache Bug. I first came to love the Evil ‘Stache Bug on my very first survey project around the village of Korfos in Greece. They were everywhere and they have these really gnarly moustaches bristling out over the big death proboscis thing they use to stab their enemies! These guys are often involved in “bug wars” and it’s not uncommon to see them and their relatives feasting upon a fresh kill.

More benevolent are the cricket and grasshopper type creatures out there in the grasses and fields of the Mediterranean spring and summer. The largest and most colorful concentration of cricket type guys I’ve ever seen was in the fields below the citadel of Palairos in Aetolo-Akarnania. I think maybe someone had sprayed pesticides on a field nearby which drove them all onto the vegetation right next to the road that leads up to the site. These are gentle insects, often observed being eaten, but they never act aggressively themselves. There are lots of different fun variations on the theme.

An adjacent category are the mantis-type creatures. In Greece there are a lot of Mediterranean mantises, but there are also some truly wacky insects that look kind of like a mantis but with Frankensteinian modifications.

In certain parts of Greece you also get a lot of different kinds and colors of dragonflies and damselflies. The gorges of southwestern Crete are especially rich in dragonflies – there must be at least a dozen types of dragonflies living just in the Preveli gorge alone! I wasted a lot of time when I worked at an excavation at Damnoni down there hunting dragonflies and trying to take photos of them. Sometimes from a certain angle they look like they are smiling at you.

Not to be forgotten in all this are the humble beetles, and other beetle-like ground dwellers. Sometimes it seems like every beetle you see in Greece is totally different than the last. The best is when the weather is a little cold and they lose their ability to move very quickly. You can pick them up and have great quality time with them in these conditions, and it doesn’t really seem like they mind too much.

Anyway, I could go on and on – there are way more categories that could be introduced: shield bugs, wormy-type larvae, shore insects and skimmers, etc. I think a lot of archaeologists could care less about all these messed up looking insects. But one of the things I really like about survey archaeology is that it makes you pay more attention to the world around you, not in an active sense, but just as a kind of habitual way of being. For me that has included becoming more acutely aware of the many small forms of life that surround us in the countryside. I have no knowledge of the scientific field of entomology, but it always seems like the variety and proliferation of bugs in Greece must be pretty off the charts.

While some of those guys – like spiders that inflict very painful bites! – can be something of a hazard to surveyors, most are totally harmless and often kind of fun to observe. I’ve only been actually scared of an insect in Greece once. My partner and I were hiking in a remote part of the Mani peninsula when a late spring thunderstorm blew down off the Taygetos massif. We took shelter from the rain in an abandoned medieval church, but as soon as we got in there we noticed that the walls were moving – the rain had driven dozens of huuuuuuuge poisonous scorpions from the nooks of the rubble walls of the church: they too were taking shelter from the downpour inside. Apparently these guys are among the biggest and baddest in all of Europe. Needless to say, we decided to take our chances with the rain.

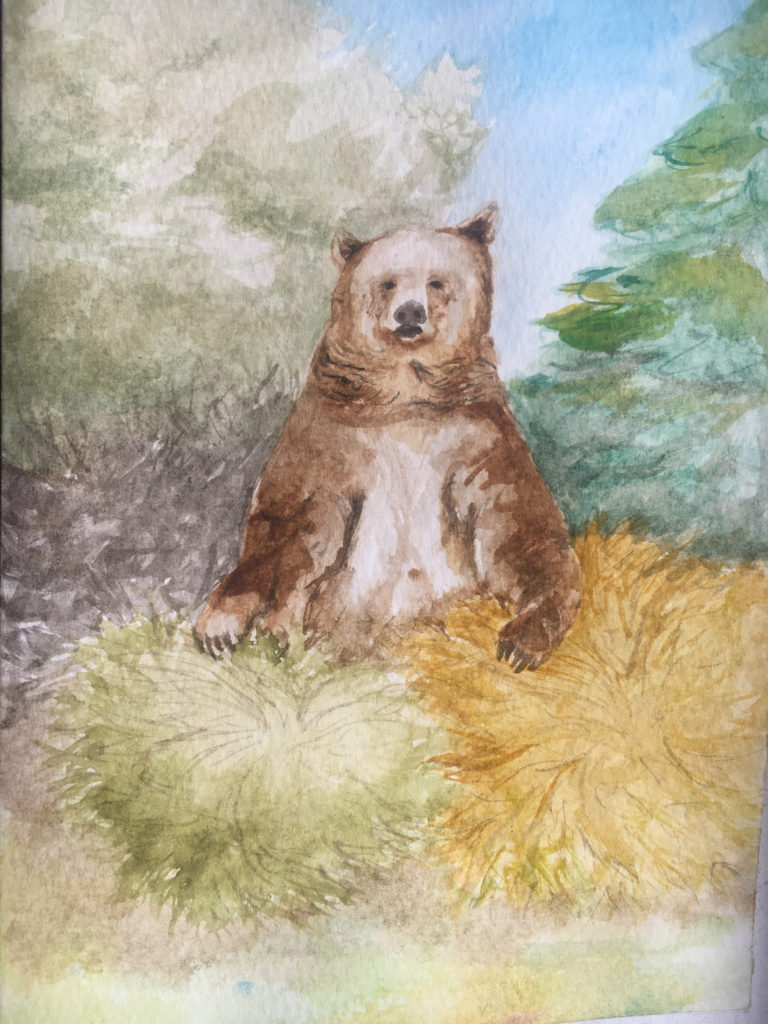

End of Season Art from BEARS 2019

There is a lot of talent on our survey project, and I’m not just talking about intellectual or academic superstardom – for example, one team member is a known unicycle phenom, and another has a secret prior career of jumping award-winning show ponies. Isabella Vesely, an undergraduate at Western University in Ontario, is a gifted artist and illustrator as well as a valuable member of the BEARS project. Last year she spent the final week of the project drawing some of the catalogued finds collected in 2019. Unbeknownst to the team leadership, she was simultaneously making a series of beautiful bear-themed cards that were presented to staff members at the end of the season. They are pretty awesome, and with Isabella’s generous permission, we now release them to the wild (or at least to the wild of the handful of other humans who ever look at this website!).