A curious aspect of the LH IIIC archaeological record around south and central Greece is the frequent appearance of settlement remains on small offshore islets that (at least superficially) do not offer a very hospitable place for people to live. In our view Raftis islet in Porto Rafti bay was probably the site of a substantial residential settlement in spite of its steeply sloping landscape, lack of an obvious harbour, and absence of available drinking water. But it is just one of many such islands, and it’s clear we’re unlikely to understand the ‘enigma of Bronze Age Raftis’ without considering it within the context of comparable sites from the same period.

One such site is located on the islet of Modi, just off the southeastern coast of the delightful island of Poros in the southwestern Saronic Gulf. In 1999, LH IIIC remains of two building complexes on Modi were excavated by the erstwhile 2nd Ephorate under the leadership of Eleni Konsolaki-Yannopoulou; additional walls and structures were evident on the slopes of the islet, suggesting it (like Raftis) was densely settled. The cargo of an apparent LH IIIC shipwreck was subsequently located off its northern coast and explored by Christos Agouridis and a team from the Hellenic Institute of Marine Archaeology. The cargo includes a large number of hydriae, which seem to have been used as transport containers.

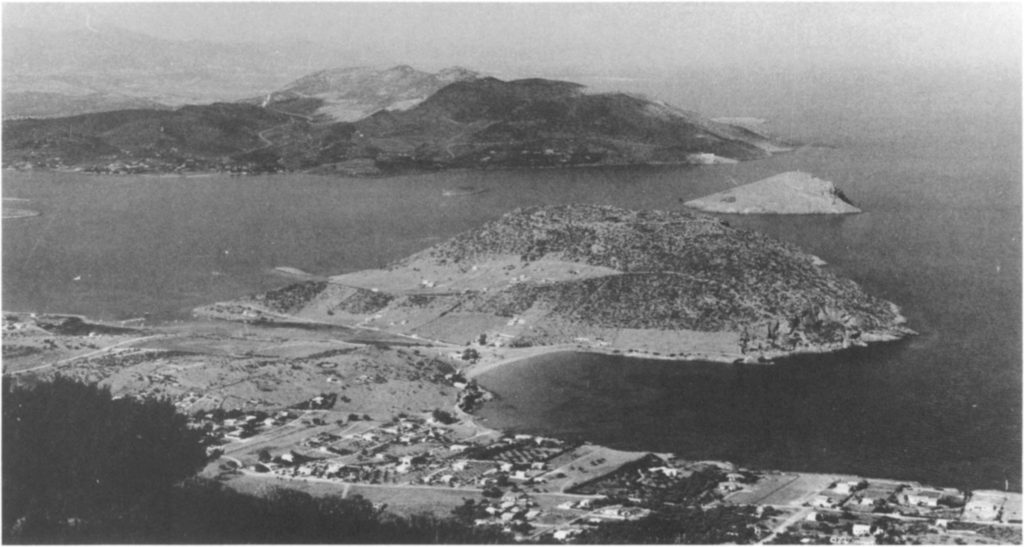

Given the islet’s position on an important sea route (the ferry from Athens to Poros still passes right under its nose), it’s not entirely surprising to find material remains there. However, as gnarly as the slopes of Raftis might seem, Modi’s extremely extreme goblin castle landscape makes it look as tame as a manicured golf course! Modi is also referred to as Liontari, because when viewed from certain angles it looks like the profile of a lion sitting in repose.

I had always been intrigued by reports from the work on and around Modi. However, I had never seen the island, or the material from the excavation which is on display in the Poros museum, until a recent trip down to the southern Argolid last week. It was definitely worth the drive – Modi looks even more improbable as a site for human settlement in person than it does in photos!

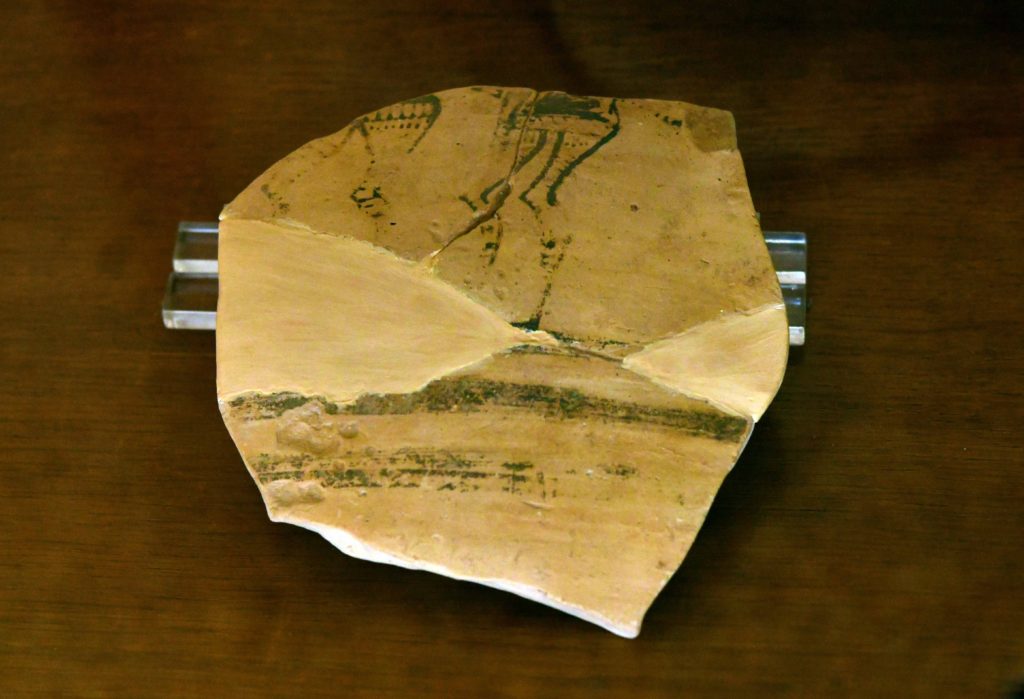

The finds in the museum are likewise very interesting to see in three dimensions. They suggest some intriguing connections with Porto Rafti bay. For example, a fancy large krater seems to be made of the White Ware fabric that we now know was being made on Praso and that is abundant on Raftis and in the Perati cemetery. Both the Perati cemetery and Modi have produced examples of pictorial pottery with depictions of human beings, which is not exactly widespread in the LH IIIC period. The finds of a strange wooden box with maybe Egyptianizing motifs added in bone inlays and a piece of a copper ingot on Modi suggest the same kinds of long-distance commercial and cultural connections observable in Porto Rafti’s material culture, too.

We can still only speculate about the nature of life on Modi in the Bronze Age, or why this site seemed an appealing spot to settle down, but we can probably bet that the community there was in touch with the Bronze Age folks in Porto Rafti, and maybe those living on other small islets in the area too. With any luck we’ll have additional insight into small islet life in the LH IIIC period by the end of our little survey project in a few years’ time!