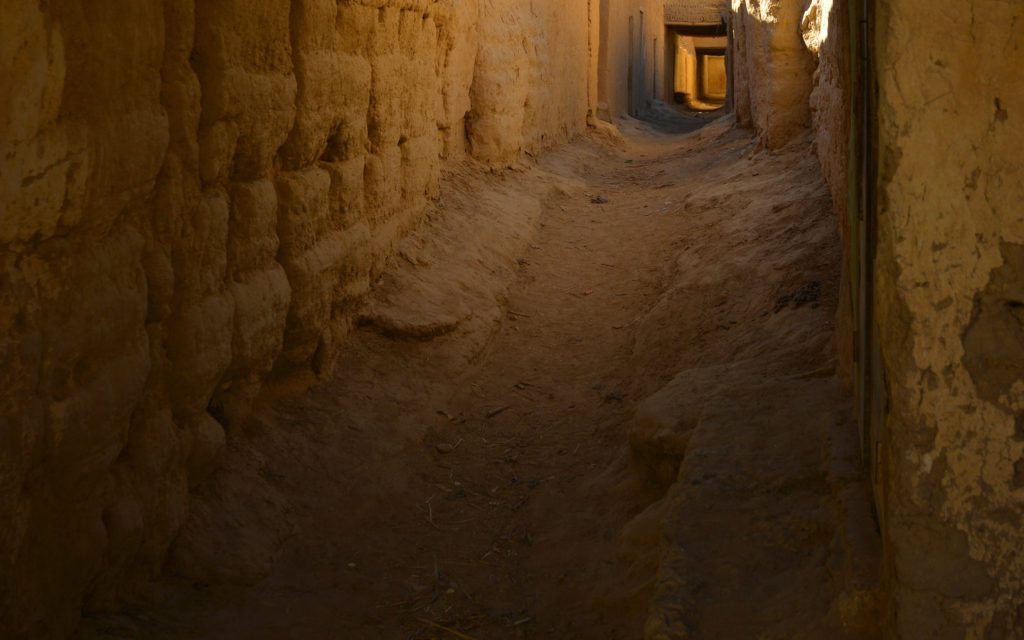

For the first two week of BEARS 2021, we’ve been working in one small team of six to tackle the previously discussed scatter on Praso isle . But thanks to some bureaucratic heroics, Maeve McHugh – leader of all things to do with Koroni fieldwork, swooped into Porto Rafti on Sunday, so we started chipping away at our Koroni peninsula survey again today. In honour of the arrival of our Koroni Captain, I offer a few thoughts on what BEARS is contributing to our knowledge of Koroni…for those who have not pored in great detail over our past reports, Koroni peninsula is a really fascinating example of a site that was excavated in part back in 1960, but about which many questions still circulate.

Some might say that BEARS has messed with the expected order of archaeological events – surveying a site that has already been excavated…can we do that?! It has been done before but usually surveys of excavated areas focus on “more modern” non-artifact collecting practices (e.g. GPR, LiDaR, etc.). Few sites have been subject to surface collection after trenches have been dug. But this is exactly what BEARS is doing at Koroni! This begs the question: how exactly does a surface survey contribute to our knowledge of a site that has already been excavated?

BEARS is technically the third archaeological survey to explore Koroni. The first was conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) in 1959, and another by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) in 1986. Although the ASCSA collected a smattering of surface finds, both of these surveys focused on architectural documentation with particular research goals in mind. For the ASCSA, this was capturing the size of the site and identifying enough of the architecture in order to make an informed choice on where to excavate. For the DAI, the project goal was a localized architectural study of buildings on the hillslope, an area of the site largely ignored by the Americans.

When the Americans returned in 1960, they excavated for three weeks in spaces that were proximate to meaningful architectural features identified from the survey. This included areas in and around major gates to the fortification, well-preserved towers, and buildings situated at topographically accessible positions. The results of this excavation changed their interpretation of the site. They no longer thought it was a deme center but instead a short-term military camp built by the Ptolemaic army in the 260s BCE. The Germans then used architectural survey, as well as a re-contextualization of many of the finds, to argue that the site was in fact an Athenian site before the Ptolemaic troops arrived. The picture of the site has hovered around the first half of the third century BCE and the research questions have been largely historical – who lived there and when?