In our short pilot season last June we had only just gotten started documenting and studying the abundant architectural remains visible on the sites of Raftis and Koroni. That was something that we had big plans for this summer, but that work is going to have to be pushed forward to 2021, or whenever our fieldwork can safely resume. To produce a proper documentation of the built remains of these sites we’ll need to spend a lot of time cleaning wall foundations, mapping with the dGPS, and (where appropriate) drawing and conducting photogrammetric recording to produce accurate stone-by-stone plans and sections of well-preserved walls and buildings.

The purpose of this work is not just to create obsessively thorough records of the archaeology of the area, although that’s certainly part of the goal. Another goal is to date the architecture based on its construction style or associated artifacts, although that’s always complicated to do in a survey context with relatively scrappy walls. We’ll also use our careful study of the architecture to try to reconstruct the original appearance of the buildings.

All of the architecture we’ve observed in the Porto Rafti area consists of relatively low-lying foundations made of rough field stones – no ashlar blocks or cut stones, at least so far.

When it comes to reconstructing the original appearance of the built structures represented by these walls, an important question is what the upper part of the architecture would have been made of. A major issue that comes into play here is the question of mud brick. A lot of architecture in the ancient Aegean was built primarily of mud brick on top of a stone foundation (which would prevent groundwater from damaging the bricks). For obvious reasons, mud-brick portions of buildings don’t survive as well as stone components, so we rarely find well-preserved mud-brick architecture, even in excavations. Mud-brick in survey contexts is basically unheard of.

One of the many strange conclusions reached by the team of American archaeologists that worked on Koroni around 1960 was that there was absolutely NO mud brick used on the site whatsoever. Apparently the guy who studied the architecture, James McCredie, came to this conclusion because there were no traces of mud-brick apparent on the walls and because there was a lot of collapsed rubble around on the ground.

That sounds like a pretty silly, flippant argument to me, and I’m guessing when we study the architecture up there more carefully we’ll find plenty of reason to believe that mud brick was used in construction on Koroni. Certainly most of the walls I was documenting on Raftis island look like stone foundations for mud-brick superstructures. In any case, those are the kinds of questions our architecture team will be chewing on next season: what kinds of construction techniques and construction materials are we dealing with, how large would these buildings have been originally, etc.

In conversations about ancient Aegean architecture, I find that mud brick has kind of a spectral mystique. Especially recently, because of my work in architectural documentation on the Mazi Archaeological Project, I’ve spent a fair amount of time working on architecture, and we talk about mud brick as a component of the built environment all the time. We know it was an important part of the architectural landscape in the Aegean, but it rarely exists for us to look at or study as a physical object. We just have to imagine what the mud-brick portions of buildings from the ancient Aegean would have originally looked like, because there is not much of them left.

Although most people might think of mud brick as a humble building material, it’s actually completely superior to stone in a lot of ways. It’s great for temperature regulation, keeping out heat in the summer and retaining warmth in the winter, like an animal burrow. The bricks can be made of of widely availably material and are easy and fast to manufacture. They are more modular and regular than, e.g., fieldstones, but they don’t require laborious quarrying, like cut stones (actually, it seems likely that the idea to cut regular stones for architecture came from the shape and utility of modular mud brick construction). As long as they are protected from moisture at the base and top, with some kind of footing and roofing, they can last a really long time, but the structures are easily modified nonetheless. Mud brick is very strong and adaptable and can be used for all kinds of things you might not expect, like vaults and arches. Even though we associate mud with grim filthiness, mud-brick architecture can be incredibly tidy and neat if it is well-maintained.

In sum, mud brick is much more boss than some people give it credit for. Whenever I travel in places where there is a lot of extant mud brick architecture I become very excited and take many photographs of mud brick buildings or remains – these are great for boring your family (or blog readers) with when there’s not much else to talk about or you want to avoid a difficult topic. On a tip from an old friend Adam Stack, I once stopped into Chachapoyas, a colonial town in northern Peru that is named after a local tribe, whose name means “Cloud Warriors”. This is not the only awesome thing about the town, but it has a lot of great old-school mud-brick architecture. Most of it is plastered over to present a cheery white colonial facade, but there are plenty of places where you can see the construction materials at the interstices. These people do a mean mud brick.

I also saw some great mud architecture in Kenya a couple of summers ago. The Kenyan villagers tend to use a much wider variety of different techniques for employing mud in their architecture than the Cloud Warriors. There were houses made of regular, mortared mud-bricks, wattle-and-daub, and a kind of hybrid multi-media wood and mud structure that I guess you could call a version of half-timbering.

By far the greatest place to check out the soaring possibilities of mud brick architecture that I’ve ever been, however, is Morocco. That is not to say that the bounteous abundance of mud brick architecture is the only or even the main reason that Morocco is an amazing place to travel. I have never, ever, been in a place with such consistently stupefyingly beautiful landscapes as the ones in Morocco, especially once you get south of the High Atlas mountains, where the geology is stripped clean of most vegetation and you can see the naked, orange-and-red striated evidence of ancient tectonic action all over the place. There are also many dizzyingly steep and epic gorges and canyons to explore, and ample herds of roaming camels and donkeys to accompany your expeditions. Once you get south of the Anti-Atlas AND the Sahel, you can check out some real honest-to-goodness sand dune fields, whose otherworldly orange glows combine with the bright blue Saharan skies to produce an overall aesthetic effect that can only be described as enchanting. The Atlantic coast is dramatically gnarly, its beaches littered with shipwrecks, sleepy diurnal owls, and confusing vistas of green coastal lushness interspersed with massive dune fields emptying directly into the sea. Yeesh, if you can visit Morocco and not spend half of time time with your eyeballs rolling back into the back of your head from too much retina-burning stimulus, you are a stronger person than I’ll ever be.

Returning to the mud brick situation, however, if you are a fan of mud bricks, you seriously ought to get out and visit Morocco as soon as you can. Once you get into the desert regions where building materials are somewhat limited, the quantity of mud brick architecture is seriously unbelievable. Mud brick is used to make everything from the fanciest palaces to everyday houses.

There are still a lot of sprawling oasis towns that are almost entirely made of mud architecture, with only a few modern concrete structures mixed in to replace failed buildings or to serve the modernizing ambitions of the few local oligarchs. There are also quite a lot of places where the mud-brick ‘old town’ has been totally abandoned, to be replaced by a new concrete town right next door. Even once they are abandoned, the mud brick villages in Morocco last for a long time because of the relatively dry climate, and so there are a lot of totally abandoned but relatively intact villages to investigate.

As I said before, not only typical village architecture but also the most grandiose palaces are made of mud brick in the old Berber villages of Morocco. It’s pretty incredible to see just how tall, intricate, and complex of a structure can be built just with dirt, essentially. The Anti-Atlas region is full of these massive kasbahs, built to house the local lords of Berber tribes. They are often really big, up to five or six stories, and the towers are usually elaborately decorated with crenellations, decorative designs that look like something from a Gothic cathedral, and arches or other forms of window dressing. Looking at these always makes me think of the ziggurats of the ancient Near East – and is a powerful reminder that a castle built from mud can be just as imposing, monumental, and intimidating as one made from stone.

Of course, not every building in the village is going to be a massive, elaborately impressive kasbah. But the less-grandiose domestic architecture can be just as interesting and impressive in its fastidious construction techniques. The mud-brick in Morocco usually involves some mortar, used at the horizontal joints of courses and containing some kind of temper, usually straw. Usually the method of bonding or stacking the bricks is relatively regular, although many different techniques can be observed, including some cool houses that combine stones and mud bricks to excellent structural and aesthetic effect. Much of the time the exterior of the bricks is plastered over with the hay-tempered mortar, and then this mortar is painted very bright colors at strategic positions like gates or windows, for an extremely jaunty effect.

In addition to the mud bricks themselves, these structures usually employ a lot of wooden and vegetal elements, especially mats or bundles of reeds available in the oueds that run through most of the major canyon and valley systems, and also the fronds and trunks of the abundant palm trees that populate the oasis towns. The roofs were usually flat and made of palm beams that supported reed or palm rib matting in between, which matting was covered over with a layer of the mud plaster. Wood was also usually used for the windows and the doors, interior supports/columns, and lintels, especially when stone was not available or considered to be too expensive. Often times the builders don’t really even bother processing the vegetal matter, so you’ll see very raw tree trunks and branches just jammed right into the construction.

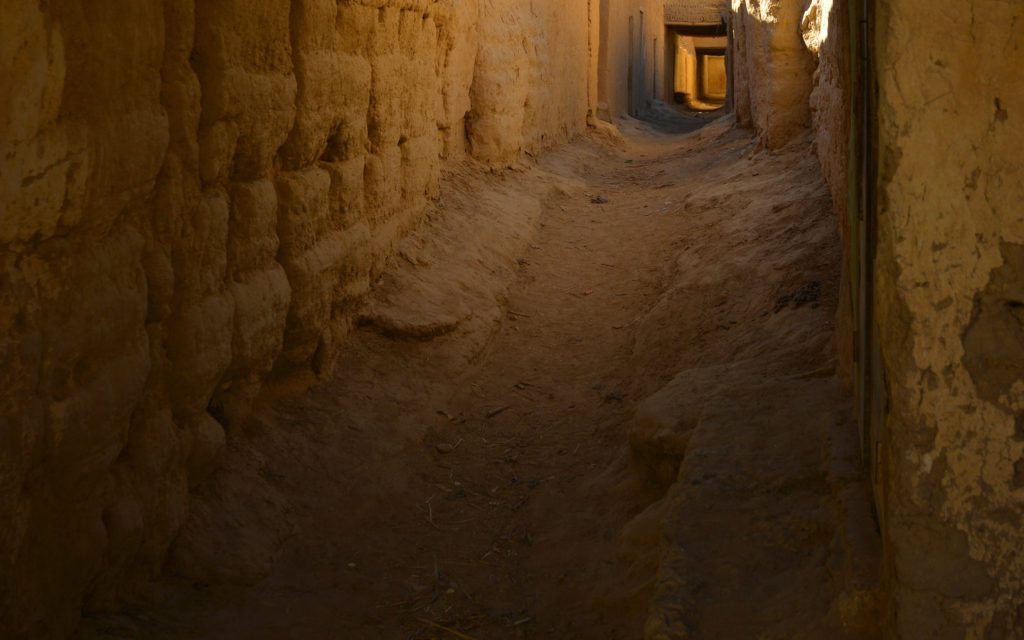

If you can only go to one area to check out mud-based architecture in Morocco, the place to be is the region of Rissani in the south central part of the country, near the Algerian border. The modern ‘town’ of Rissani comprises a cluster of structures called ksour, groups of neighborhoods or communities surrounded by massive defensive walls and accessed through monumental gates – all of which (houses and defenses) are made of mud-brick. Inside those monumental gates are whole small, sheltered worlds of mud-brick. You can usually even find stacks of raw materials lying around, too, like palm trunks and buckets of sludge for mortar repairs. People still live in these places, which is good, because it is easy to get lost in the warren of intricate passageways, and you’ll often need help finding the way out.

Anyway, Rissani is amazing! I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to learn more about mud brick architecture and how much a good builder can achieve with it. That said, of course it is very unlikely that the mud brick architecture we’d be reconstructing for either Koroni or Raftis was anything so magnificent/elaborate as any of this Moroccan architecture. But, just in the abstract, it’s educational to spend time around real-life specimens of mud-brick, because they give you a real sense of the advantages and possibilities of the material.

In the Aegean it seems like we have a real bias towards the study of hard things – especially rocks and ceramics – which often leads us to underplay the importance of the kinds of materials that don’t survive as well. I think there’s also this conception in our field that something monumental must be made of stone, and that something made of mud brick was not so impressive. But checking out some real good and proper mud architecture in Morocco will quickly disabuse anybody rational of that notion.

I’m definitely not on board with with McCredie’s argument that Koroni couldn’t have had any mud brick architecture. I wonder if he thought it would be unmanly for his military camp occupants to use such a weak, soft material for building their fortification walls…or maybe he thought that these guys were in such a hurry to throw up a wall for their sudden Chremonidean war needs that they couldn’t have been bothered to manufacture any special material for construction. Anyway, who knows – those are just my stray thoughts for the day. For now the team is stuck indoors for the most part, so we’ll have to wait and see what we come up with in terms of architectural reconstructions after additional study of the walls next year.