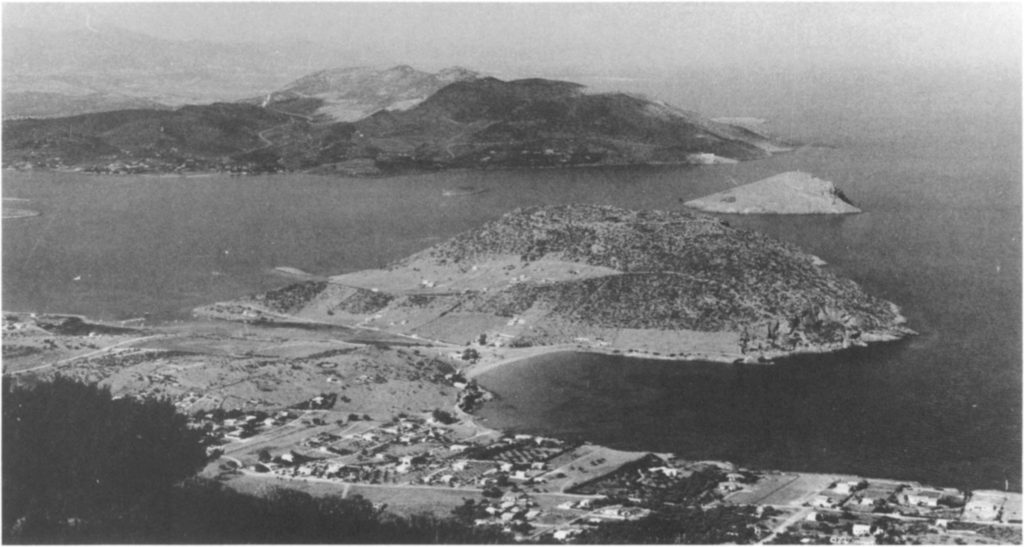

The archaeology of Porto Rafti bay is top shelf, as the BEARS project demonstrates every time we wander out into the field. From the delectable obsidian debitage gravel pit that is the Pounta peninsula to the delightfully abundant and surprisingly diverse array of Koroni tiles, not to mention one of the more interesting human coastal ecosystems known in the entirety of Greece for the LH IIIC period, and a smorgasbord of Roman dinner-party pots on small islands, it’s got something for everyone!

Of course, as an archaeologist devoting many years to work and study in the bay, I’m not exactly an impartial source for such an opinion. But I think it’s not too controversial. Anyway, in just two short seasons with a pretty small team, the project has already generated a huge amount of new material and exciting conclusions. We have a ton of stuff to study and think about ahead of putting together a complete publication over the next several years, which is going to be so much fun.

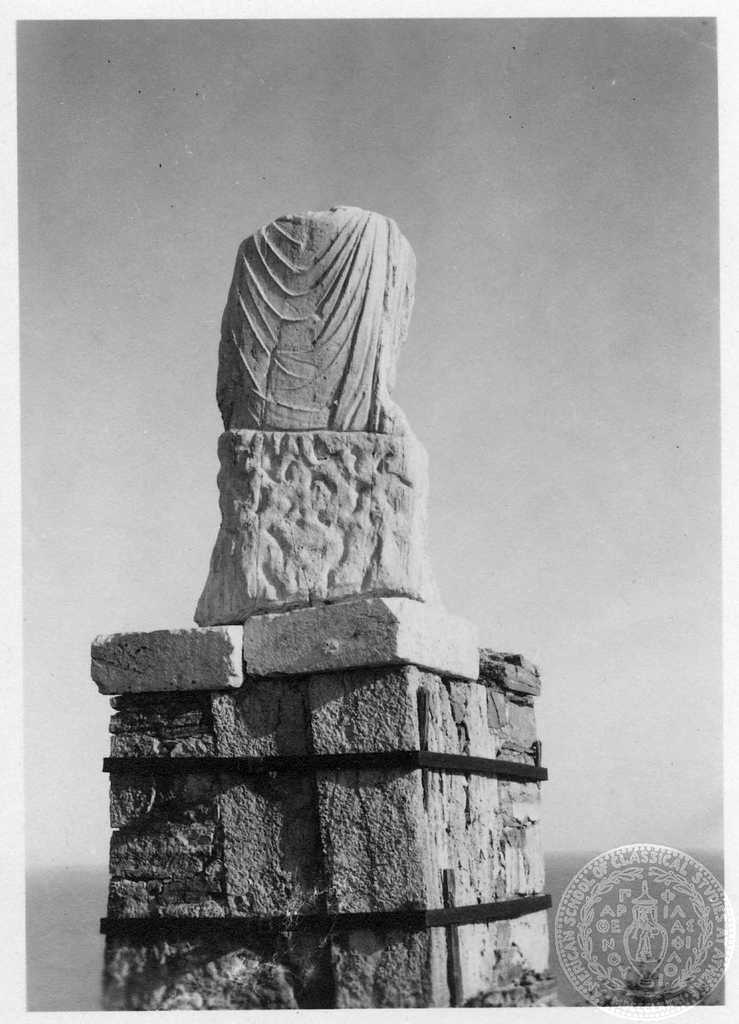

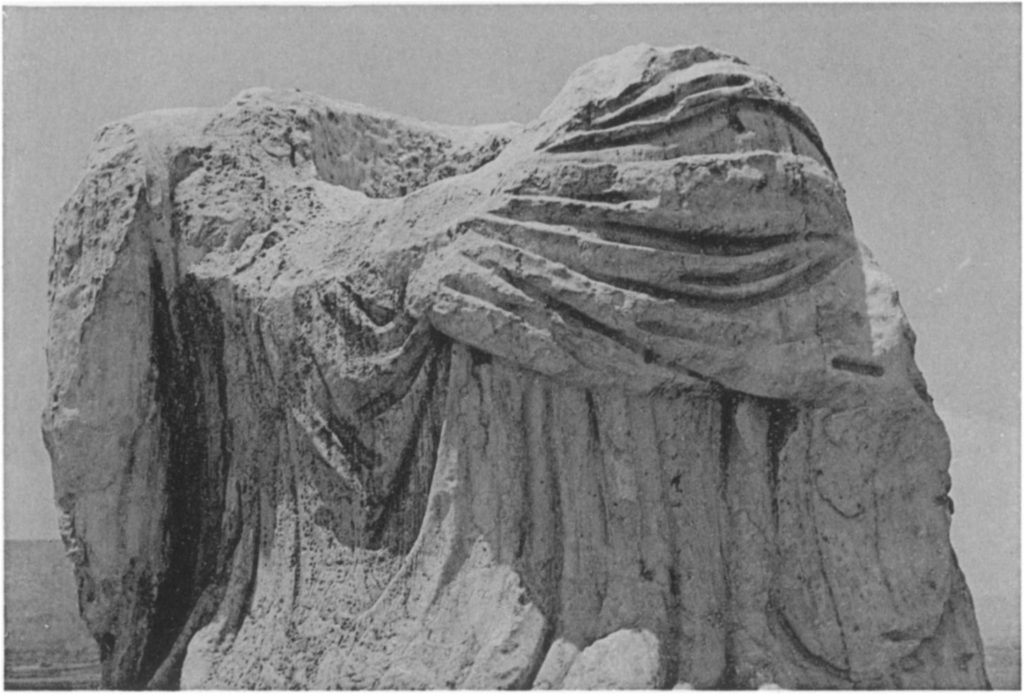

The one aspect of the archaeology of Porto Rafti that we are not much concerned with in the project, at least so far, is the Raftis statue that gives the bay its name. Our project has a lot of goals, but saying or doing anything related to the Raftis statue is not exactly a priority: surely plenty has been said and done about that beaten up lump of marble already. As is well known by now, the statue does not actually represent a tailor, and is not male – most agree that it represents a female goddess, perhaps Demeter, that it was originally carved in the 2nd century CE, and that it was moved to its current location sometime after that.

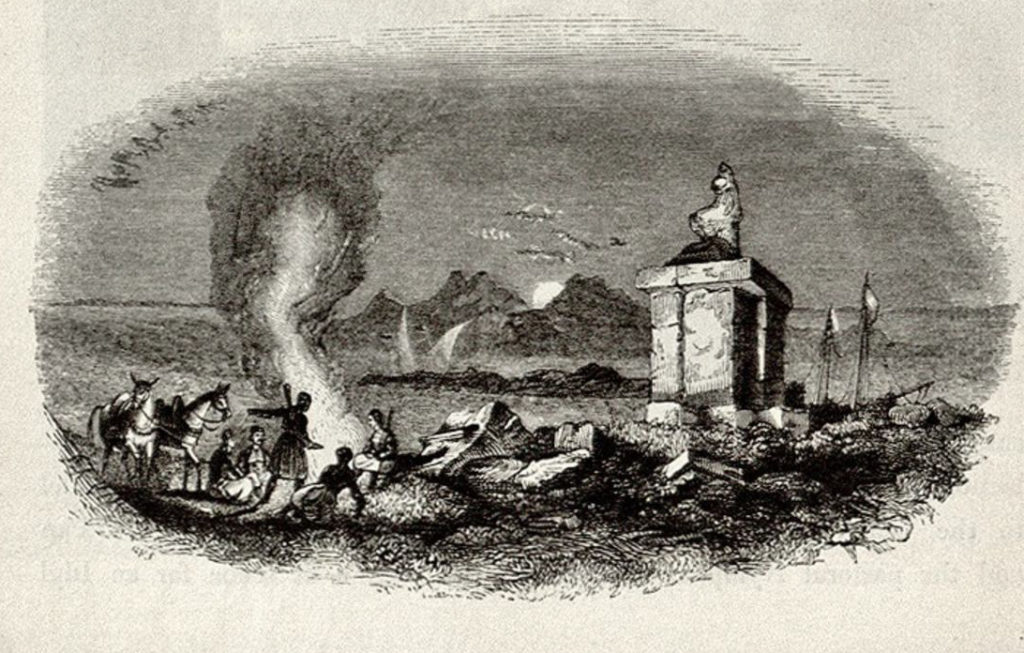

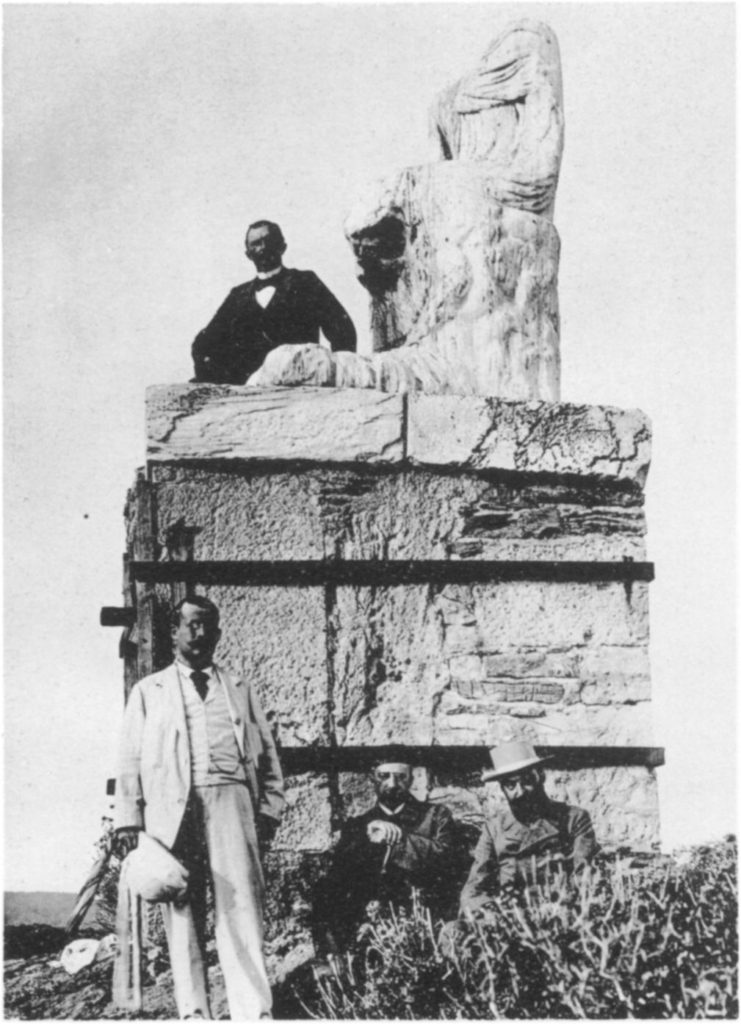

Basically every traveler who came near Porto Rafti prior to the 20th century mentions something about the statue; apparently it was one of the main attractions that drew people to the bay back when archaeology mostly involved travelling around Greece looking at stones left over from antiquity. Even as late as the 1960s and 1970s special expeditions were formed in order to assess the burning questions of what the statue represents, where it came from, and the particularities of its aesthetic merits:

“Notwithstanding the damage, the statue has many points of aesthetic power and forceful beauty. The posture still evokes a feeling of formal majesty, and the view of the right side shows the rhythmical transitions from cloak to body to rockwork seat and plinth, conveyed in the bunching of drapery and the depth of cutting.” (Vermeule, 1962: 63)

Oh yeah: Forceful beauty! Formal majesty! Rhythmical transitions! I am not sure I see all of that in the old lump, but I’ll leave that for the art historians to decide. Let’s just say the work we are doing in the BEARS project is not so wrapped up in formal majesty or rhythmical transitions.

That said, some extant stories from the history of peoples’ attempts to answer questions of what the statue represents and where it came from are pretty amusing, and also shed interesting light on the history of post-antique activity in Porto Rafti.

In 1740, some locals apparently told Charles Perry of Penshurst that Apollo granted a particularly competent tailor the honor of the statue when he “reigned King of Greece”…whenever that was. The idea of the statue as a tailor therefore goes back at least into the 18th century, and probably earlier. A common story is that the statue once held a pair of golden scissors, since stolen.

But there are totally different, and probably earlier origin myths for the monument. According to Niccolò da Martoni, who was in Porto Rafti way back in 1395, the local story of the statue concerned a young man who fell in love with a beautiful girl uninterested in his advances. The girl ran away; despairing during the pursuit, she asked the gods to intervene. The gods turned both the young man and the girl into marble, then set them up on two nearby islands – hence the names of Raftis and Raftopoula. This story corroborates other accounts, including those of Guillet (ca. 1670), Perry (1740), and Stuart and Revett (1753) who saw two marble statues in the bay.

What happened to the other statue? The letters of John Morritt dated between 1794 and 1796 describe the activities of Louis Fauvel, a French painter who collected large quantities of antiquities with which to decorate his house and that of his patron (the Comte de Choiseul-Gouffier), in the general area. A plausible suggestion brought forward by Vermeule is that Fauvel made off with the statue from Raftopoula during a general looting tour of Attica.

And the poor old Raftis statue’s head? According to Collignon’s summary of the French consul Giraud’s correspondence from the late 17th century, a nasty Venetian ship captain whacked it off for a souvenir sometime around 1673! Such drama, such intrigue. By the way, Collignon wrote a really fascinating account of 17th-century Porto Rafti based on Giraud’s letters: apparently there was a booming nut export business going then, as well as outgoing shipments of Attic resin, honey, and silk. Many distinguished foreign consuls and merchants were in residence, and had various disputes over taxes with local sailors and officials. Clearly a lot had changed by the time of Dodwell’s visit in 1805, when the entire area was abandoned!

An interesting suggestion by Vermeule is that the statue could have been used as a lighthouse to keep sailors from smashing into the Raftis islet at night, which is a cool idea. I can imagine that this big marble figure with a sort of Headless Horseman flame head lurking atop the pyramid of Raftis would have looked very very extra!

When it comes to any of the other questions about the Raftis, where the statue came from or who put it there, most of the accounts related to the statue are impossible to corroborate, and several contradict each other, so it seems very unlikely that additional efforts to enlighten its background would be fruitful. Of course, there’s always more room for idle speculation, but maybe that’s not the best use of BEARS’ time. It is helpful that the statue has been there drawing travelers to the bay for hundreds of years, since their other comments give us interesting accounts of what the bay was like a long time ago. Too bad they didn’t know how to read surface pottery, or we’d also have a better idea of the extent of ancient settlement in the area too.