One of the questions that we are trying to address with the BEARS project relates to the bigger issue of what was going on during the twelfth century BCE, after the so-called collapse of the complex ‘palatial’ states that loom large in the material record of the Aegean before that. The question of how society developed in this period is absolutely my favorite professional research topic. This is not unrelated to my lifelong romance with post-apocalyptic fiction – in turn, the general popularity of this genre proves the point that we humans are eternally fascinated by the idea of moving forward with life amidst various kinds of aftermaths.

My particular perspective on life in the post-collapse Aegean has been strongly influenced by travels in other parts of the world, where (unlike most places I’ve lived in North America) you are often surrounded by ruins of the recent past. None of these contexts provides a perfect analogy for what happened in the Bronze Age, or any archaeological situation, obviously, but I find that wandering around among recent ruins is evocative in a way that just thinking intellectually about the LBA collapse is not.

Although I’ve had a lot of interesting experiences along these lines in many places, I have come up with many of my best ideas about what happens when you are living in the aftermath of a collapsed state while traveling in Georgia, which used to be a part of the Soviet Union.

There are all kinds reasons I would recommend Georgia as a destination for travel – the people are extremely kind, fun, and welcoming; the food and wine are seriously unsurpassed (and I don’t even like food or wine that much!); the natural environment is stunning and hugely varied from region to region; there are SO many awesome barnyard animals everywhere (my favorite thing); it’s cheap as heck; the driving is an adventure; the birding is spectacular – I could keep going.

But as an archaeologist, the most fascinating and rewarding thing to me about traveling in Georgia is the ruinous landscape situation – Georgia is full of all sorts of ruins and crumbling, forgotten monuments, sometimes sitting cheek-by-jowl with state-of-the-art modern police stations and megamalls. Unlike the situation in Greece, most of these ruins are not what we’d usually call archaeological sites. Most of the ruins in Georgia are remainders of a very recent past, a past during which life in the country was very different from how it is today. They are mostly ruins and images from the 1940s to 1980s, left behind in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Georgia has an interesting relationship with its Soviet past. I won’t go into too much detail, and obviously I’m not an expert on the topic, but let’s just say that the region has a long, proud historical tradition and culture of its own (Davit the Builder, ya heard?!), and Georgians often chafed under the Soviet regime. They officially declared independence from the USSR in March 1991, before its official dissolution in December 1991. The new Georgian state has – more or less – enthusiastically embraced democracy and the cultivation of an Europeanizing cultural identity since then. Although the Abkhazia/South Ossetia situations make it clear things are, as ever, quite more complicated than they might appear to the naive outsider, from my experience there does not seem to be a lot of nostalgia for the Soviet past in most places there.

On the other hand, probably the most famous Georgian in history is a fellow from the city of Gori originally called Joseph Jugashvili, better known to the world as Joseph Stalin. Obviously Stalin was a bad dude, and lots of Georgians, especially intellectuals, were persecuted and killed under Stalinist rule. Many others died of hunger or other collateral effects of policies put into effect by Stalin. But there seems to be some residual pride in Georgia about their most famous son, especially regarding his role in leading the Red Army against the Nazis in WW II. In Stalin’s hometown of Gori, you can still visit a big hagiographic Stalin museum and purchase sundry Stalin-themed merch in the gift shop on the way out.

Even more amazing from a western point of view, a massive, very monumental statue of ol’ Joey Steel in the center of Gori was only destroyed in 2008, in the aftermath of the Russian bombing and the eruption of conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. If you travel around Georgia you will still see vivid portraits of Stalin on a regular basis. Usually, but not always, these are part of WW II memorials – which have often been both actively maintained and spared from vandalism out of respect for the war dead, unlike a lot of other art from the same period. Staggering numbers of Georgians fought and died in WW II, and the people are rightly proud of the sacrifices they made in that conflict.

On balance I think it’d be fair to say that there’s more ambivalence about the role of the Soviet past in Georgia than you might find in some other places. For whatever reason – residual pride in the Stalin connection, a generally reticent attitude towards destruction of art, or disinterest in wasting a bunch of time thoroughly dismantling all remnants of the Soviet past – many vestiges of the Soviet era remain.

As an archaeologist, and someone who grew up in the United States in the 80s, when the Soviet Union embodied all of the bad guys and scary ideas in pop culture, nuclear shelter drills were part of grade school preparedness routines, and films like War Games captured every young kid’s imagination, I find being immersed in these ruins endlessly fascinating and bewildering.

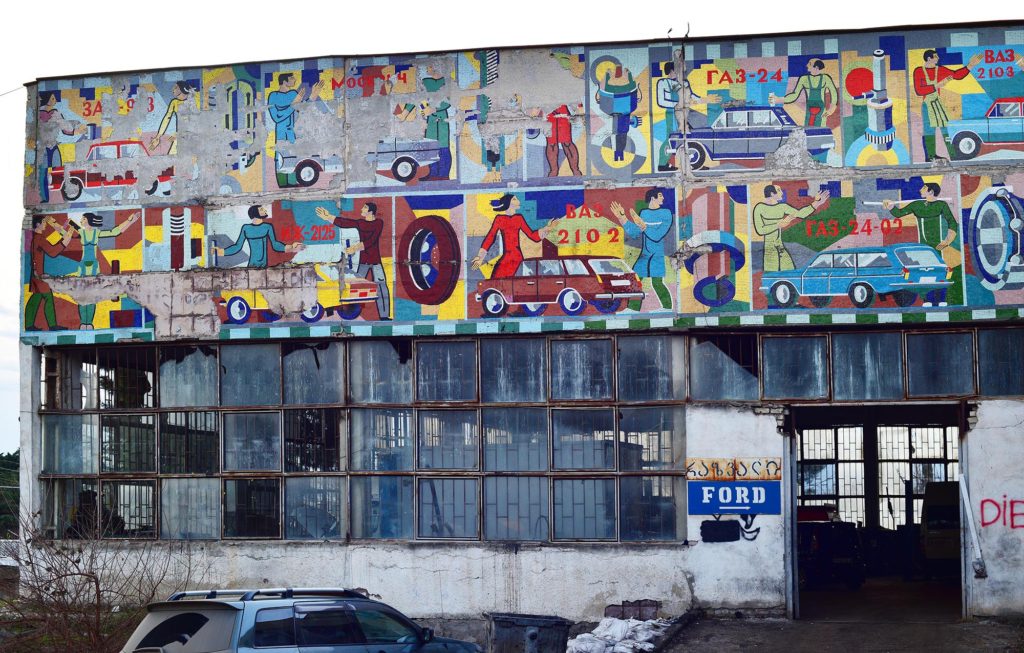

I will never forget the moment that I saw a massive propaganda mosaic looming from the giant vertical expanse of a factory wall in Georgia for the first time, in the summer of 2013. I was totally agog and spent like an hour freaking out about it, and couldn’t think about anything else for days. The aesthetic is very different from what I had ever seen in western art – the subject matter, too, but there was something completely stupendous to me about how differently the conception of the human form and the presentation of society’s ideals and all that kind of stuff seemed to work compared to what I was used to. Not to mention the fact that some of those mosaics are amazingly beautiful and seductive as design masterpieces. I can see why nobody wanted to destroy them, even though they come from a past about which people are ambivalent. But it’s also clear that the independent Georgian state hasn’t shown any interest in preserving them. A lot are in bad shape, crumbling off of walls or being papered over with political adds.

Some compositions are very virtuoso, although you can really tell the difference between the early, technically perfect ones from the Soviet heyday, and the sloppier 1980s ones from when the wheels were starting to come off the state. I can imagine that budgetary cuts to the propaganda mosaic department in the late 80s were a lot like those being handed down to humanities departments at red state schools in the US right now!

Anyway, I really can’t get enough of these things. It’s so amazing to me when I think about the nasty realities we were taught about the Soviet Union growing up in school, to be in a place where you can see the story the state was telling inside of its borders at the exact same time. It’s all these bright, cheery depictions of happy workers and science heroes and fecundity and people dancing and making wine!

Although the happiness of the workers is very likely to be exaggerated in the mosaics, it’s actually true that there was a lot of industrial work being done in massive, purpose-built facilities in Georgia under the Soviets. That brings me to another category of recent ruins that dominates the landscape – huge, hulking industrial complexes that were obviously designed to satisfy the demands of a sprawling empire, but which were mostly abandoned after its demise. The best place to go and see these decaying industrial landscapes is the area around Rustavi, just southeast of Tbilisi, but there are a lot scattered all around the lowlands and valleys between Tbilisi and the Black Sea, too.

Rustavi’s dystopian landscape of concrete communal housing blocks was obviously the home of a huge army of workers that populated an even bigger complex of steel-production facilities. A few of the Rustavi steel working plants have recently been bought up by Indian companies and repurposed for the modern era, but others are still being picked through for scrap glass and metal. The noxious fumes emitting from the biggest Rustavi steel plant ruin suggest that it probably got destroyed by some superfund-type disaster that never got cleaned up, so nobody really hangs out there.

But some of the other facilities are still in use informally – as smithies or places to harvest equipment and other materials needed for construction, home repair, or whatever. People are not exactly wealthy in the Georgian countryside, so I think for them it would be hard to afford, say, a new tractor. If one is lying around and you can get it to work, why not use it? You have to admire their determination to keep on cracking away with whatever industrial equipment the Soviets left behind until it no longer keeps on keepin’ on itself. Tractors, excavators, conveyor belts, welders – you name it, you will see mid-century CCCP equipment still in very active use all over the place. And if something won’t work as what it was intended to be, you can always be creative and find a way to use it for something else!

By far my favorite place in all of Georgia is the town of Chiatura, located in a dingy, usually rainy ravine in the Caucasus foothills not too far from the western border of the breakaway region of South Ossetia. I won’t talk too much about Chiatura here – you can read about it in Slate or Atlas Obscura instead. Long story short, Chiatura was developed as a mining town because the ravine in which it’s located is rich in manganese. To help get workers around the complex topography, the Soviets built a series of low-tech cable-cars in the 1950s. You could still ride around on them when I visited in 2013, 2014, and 2016, but one by one they are falling apart and being cannibalized for spare parts. The old mining facilities are also being used in the same manner – until they stop working. Whenever they do, they are reused for other stuff – in 2016, one old disused mining facility was being used by a group of shepherds to tan hides.

In general, given our western culture of waste and constant replacement of old stuff as soon as something better comes along, I think it’s cool to see how resourceful the Georgians are at making use of whatever is around them that can still be made useful. I once saw a guy using a three-legged chair as an umbrella! Talk about thinking outside of the box.

Aside from industrial ruins, another coherent set of ruins in Georgia are Soviet-era cultural amenities. Because Georgia is a relatively mountainous country and home to a number of mineral springs, the Soviets developed some nice resort-type spa towns for wealthy plutocrats to visit on their vacations. So far I’ve only been to two of these – Tskhvarichamia near Tbilisi and Tskaltubo out west near the city of Kutaisi. Outside of Tskvarichamia is a long cinder-block wall covered in a series of colored terracotta relief panels that presents one incredibly complex and intricate propaganda tale – I’d need a whole other post to cover it! And there are some cool other ruins of statues there. But most of the fancy spa hotels of Tskhvarichamia have – in tried and true Georgian way – been repurposed, this time as makeshift, not-exactly-on-the-books apartments (Georgians are seriously superninjas of splicing into power grids).

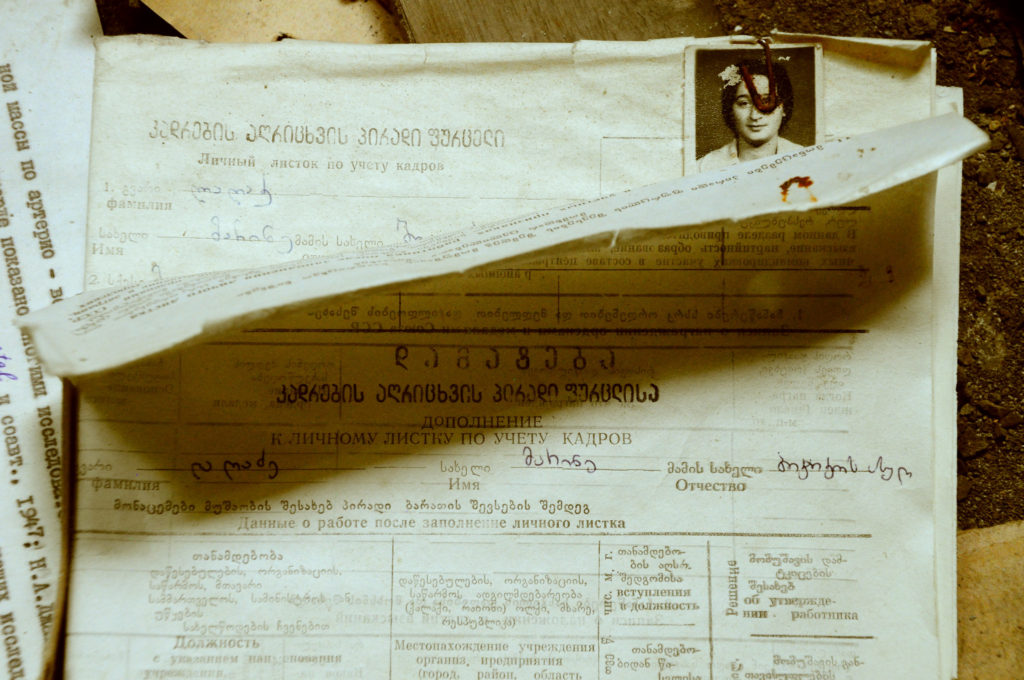

Tskaltubo is in the midst of being revived as a mineral spa bath town, so most of the squatters have been kicked out of its fancy old spa buildings, making it possible to wander in and check out what was left behind. Inside the ruins of those spa baths were a lot of papers, photos, and objects from back in the good old days when the apparatchniks descended on the town for feasting and sport, and maybe the not so good old days when sick people visited to take the cure of the mineral waters and healthy airs. If you were an archaeologist of the Soviet past I can imagine that stuff would be a real treasure trove of documentary and artifactual evidence.

One of the few common types of ruin in Georgia that seems to have been more or less left intact, but mostly gutted, and never repurposed or reused is the Stalinist theater. Almost every town in Georgia has a big, empty, ruined Stalinist theater. I’m guessing people were forced to go watch propaganda films in these places, and maybe they don’t have so many fond memories of that. Or maybe the buildings are just too specialized to have much use for modern communities.

The last type of Soviet ruin I’ve encountered in the Georgian countryside are the remains of obviously military installations. These have a completely different demeanor these days than any other Georgian ruins – they have obviously been purposefully and completely annihilated, and stripped down to a bare core of useless concrete. I’d guess that the Soviets intentionally and completely destroyed any useful military emplacements prior to pulling out their forces, for the obvious reason that the independent Georgian state couldn’t turn around and use any of the military technology or equipment against them in future conflicts. But I don’t really know the story there.

Something that really strikes me about this material is how complicated a picture of the relationship of people with the past and their built environment it presents – even in a case where the “collapse” in question was something so dramatic, so global, and so definitive as the demise of the Soviet Union. While some stuff was obviously annihilated or gutted purposefully, like the military bases or the theaters, a lot of things remained in use or were kept up, and still others were just passively left to die a natural death. Thinking about this always reminds me that the story of the post-Mycenaean period must have been complicated and piecemeal too. Not that it’s an exact analogy, but I just find that physically moving among these ruins provides a lot of food for thought when I come back to consider the Bronze Age.

It also makes me kind of sad that I didn’t study material culture in post-Soviet circumstances instead of post-Mycenaean ones in college and grad school. Not that I even knew that was a topic at the time – I tried to take a Russian literature course as a freshman at Dartmouth but couldn’t hack it and basically failed out – or that it’s an obvious thing someone would study now. Anyway, it’s too late for me! I am not sure if there is any good English language scholarship on the history and reception of these monuments in places like Georgia, but it sure would be a fascinating book to write for someone with the requisite language skills and art historical training.