Editorial Note: This post was written by Irum Chorghay, a University of Toronto student, for whom BEARS was an inaugural experience with field archaeology, after the first week of survey.

My first day as an archaeologist, I get to take a small boat out to Raphtis Island, one of three sites that our survey is focusing on exploring. We are staying in Porto Rafti, a resort town not far from Athens, and it is immediately obvious that this is not a typical area for an archaeological project like ours: a town full of beachgoers is very different from the usual rural landscape of surface survey. Each member of our crew for the day takes a walk along the narrow wooden ledge that bridges the gap between the edge of the harbor and the ship itself, and at seven in the morning, we’re tucked into the captain’s vessel and headed towards the mysterious island site.

When we arrive on Raphtis, I’m struck by how steep it is. Accustomed to the terrain of the city, I stumble hastily up the rocky, uneven side of the island, unsure of where we’re headed, or if the ground will ever even out (spoiler: it doesn’t). Dr. Catherine Pratt—one of the project’s directors—takes me and the three other undergraduates off to one end of the island, while Dr. Sarah Murray—the other project director—takes off with Dr. Robert Stephan—her right hand man—to set up the rest of the “grid.” I don’t know what this means yet. Dr. Pratt shows off pieces of pottery scattered on the island’s surface, the bits and pieces of ancient amphorae littered across the low-lying greenery. “The sherds with deep-set ridges and refined firing are Roman,” she tells us. Cassandra—a fellow undergrads—yanks a chunk of pottery out from underneath a small bush, and Dr. Pratt is thrilled. “It’s an amphora handle!” she exclaims, and the rest of us excitedly gather around her. For the most part, this is how we learn: closely examining the ground, picking up sherds and bringing them to Dr. Pratt until we learn what pottery looks like.

Next, Dr. Pratt guides us through gridded collection, and I learn what Dr. Murray and Rob were up to with their brightly colored flag tape. They have divided the island into a grid composed of 20 by 20 meters units, and each grid square is given a name according to the flag at its northwest corner: A1, A2, and so forth. We are told to do “total collection,” which turns out to be a long and painstaking process of collecting every sherd we see in the selected grid. We fill something like eleven of our large sized plastic bags with pottery and come out with just over a thousand sherds in total. I am told this is highly unusual and that this site is incredibly rich with finds. From here, our directors decide that we won’t be keeping all of the sherds that we collected in the unit: considering that we are a small team working within a limited space at the apotheke (the museum where we process and store our finds), and that there is redundancy within the information provided by these finds, selective sampling, Dr. Murray tells us, makes the most sense. At some point, I am struggling to navigate the uneven terrain, and I slip and fall face-first—only to find a large sherd of painted pottery. Dr. Pratt squeals again, and I learn that such a find—painted Mycenaean pottery on the surface—is almost unheard of, and I am reminded—neither for the first nor the last time—that this is a special project.

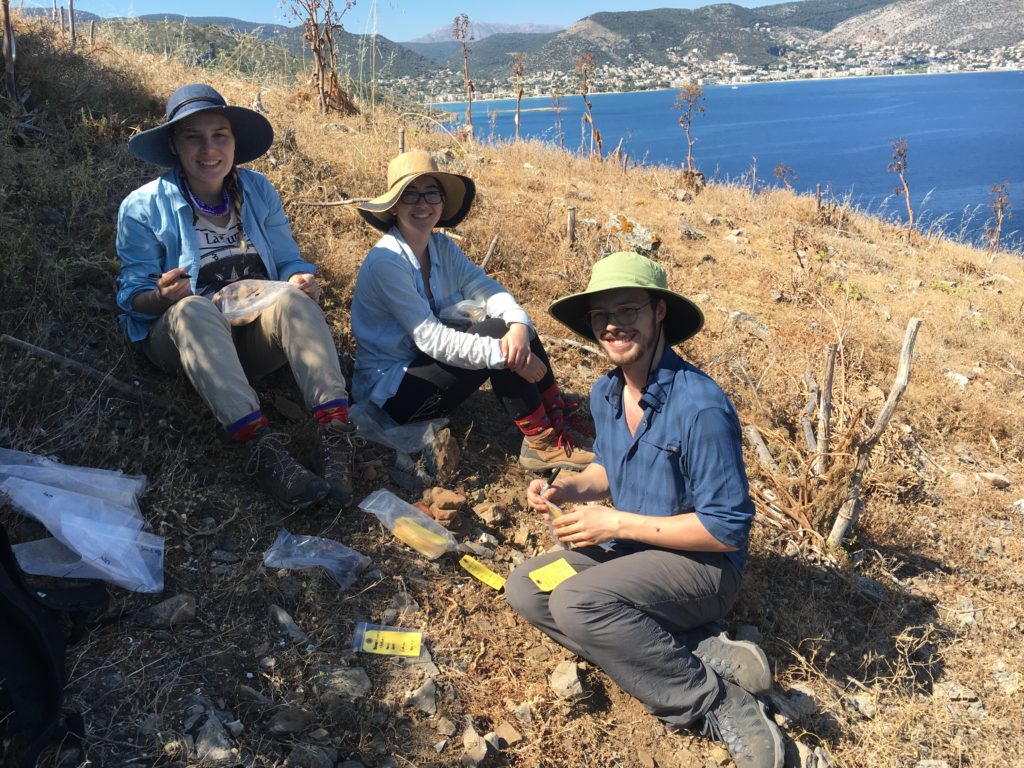

For the rest of the week, the days I spend on the field are at the site Koroni, located on a peninsula on the south side of the bay, where I continue learning how to conduct gridded survey. We start out collecting in a small valley with variable visibility—entire survey units are sometimes covered in thick and impenetrable greenery that is as spiky and as tall as our surveyors. Koroni is not as rich with pottery as the island is, but we discover several amphora handles, roof tiles, pithos (jar) rims, and bases anyway. At the end of each day, we sit on the porch and empty our hiking shoes of burs and bits of greenery we’ve picked up along the way.