Editorial Note: This post was written by Kat Apokatanidis, a University of Toronto PhD student, about work on Raftis Island.

I am driving my team to the harbor today and even though I am wearing sunglasses, the morning glare of a Mediterranean sun in the summer is formidable. I hastily pull down the overhead blind. The car is silent as the grogginess of sleep is wearing off and a subdued sense of excitement is settling in, familiar by now to any team tasked with working on Raphtis island for the day. This morning is quite windy, and so the swelling of the sea is more robust than usual. I drive the car in keeping with the speed limit, but so early in the morning it is a test to my self-control not to go a little faster since the road leading to the harbor is deserted. Muted conversation between the passengers starts picking up as the coffee is slowly doing its job; soon the car comes alive with discussion. The topic? Of course, what we might discover on the island today.

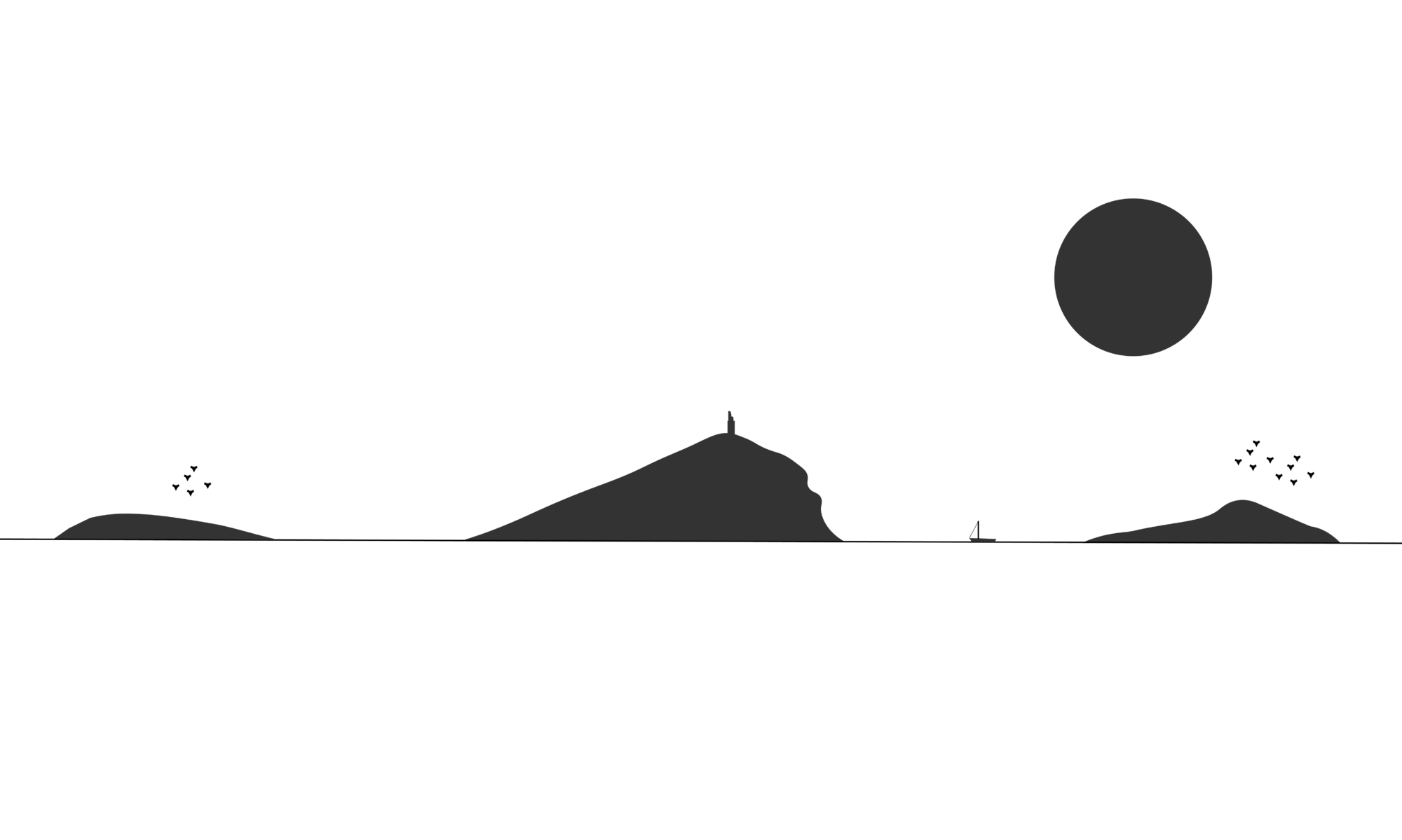

The island of Raftis is peculiar. It is a pyramid-shaped rock standing watch over a small harbor in Northeast Attica, Greece. Even though this specific bay of Attica, Porto Raphti, looks out to a strait of water between the Greek mainland and the enormous island of Euboea rather than the open Aegean, you can tell that the island of Raftis, situated between the bay and the larger island, takes quite a beating from the sea and the winds. Abused by the elements, the island is a visual reminder of what the war between earth and sea looks like. The island is completely desolate, its only inhabitants a badly eroded marble statue of a headless, seated and clothed figure, and a rusty, perfunctory light post, both situated at the top of the ‘pyramid’. Well, let’s not forget about the spiders; so, so many spiders! Every morning’s climb from the boat up to our survey unit is an exercise in avoiding webs. I am convinced that no other archaeological project has been attempted on Raftis because of these multilegged natives; a claim for which I will never have any proof yet believe in with all my heart. But, aside from its inhabitants, the island itself is quite demanding to climb and quite physically taxing to work on. It is not like the lowland plains of the site of Koroni, or even the Koroni acropolis which is relatively flat once you reach the top. On Raftis, as my ankles unhappily discovered, there are hardly any flat surfaces to be found whatsoever.

Despite this seemingly unwelcoming topography, the island of Raphtis is amazingly dense with evidence for ancient human habitation. The information gained from the existence of these artifacts on the island contrasts with the landscape itself. Steep and jagged as it is, the question that plagues the team day in and day out may be briefly stated as follows: what were all these people doing here all those years ago? And the immediate follow-up question: how different must the landscape have been in ancient past to allow for prolonged stay? There is no obvious water source and no safe harbor to lay anchor. Our project’s boat captain is hard pressed each day to find a suitable position to drop anchor. And yet there we were, picking up artifacts from the surface left and right. Each day of survey produces a lot of surprises, and so it is no wonder that all bets placed in the car on this windy summer morning are fair.

I pull into the harbor and put the car into park. We each hoist our backpacks and head over to the Plank of Doom, or the Catwalk as the local salty sea dogs call it; the Plank of Doom – as I quite accurately call it, is a (very narrow) piece of wood that connects sweet, sweet land and our amazing boat. Land? I love; the boat? She is glorious! The plank connecting these two? I loathe with a vehemence. I distinctly remember the first time I was to cross from land to boat: for the life of me, I could not make my legs move. Frozen to the spot, in vain did I repeatedly order my legs to just move, but they would not listen. This is it, I thought at that time, early in on the project, as the seven-a.m. sun was beating down my brow; there go all my archaeology dreams. Thankfully, the Captain stretched out his hand and helped me on board, and by now the daily ritual of walking the plank is no big deal.

This morning the boat rocks slightly as the currents and the winds are relatively strong. During the short journey across the bay, gazing towards Raftis and the whole landscape of the bay, we usually all think the same thing: how do we reconcile the current un-inhabitability of the island with the clear evidence of ancient inhabitants. In a way, Raftis island is the perfect place for demonstrating the utility of survey projects: the feeling and experience of a barren modern landscape contrasts with the evidence of life in the past. As the cliffs of Raftis come into sharper focus and the boat speeds toward to the island, I take a deep breath. I look around at the faces of the members of my team. All are obviously eager to find out what artifacts we might uncover, and how this improbable rock might redefine our understanding of ancient Attica. I remember the bet I placed with the others in the car; who knows, maybe I will find a temple of Dionysos up here.